Why we shouldn’t judge a book by its cover

In this week's guest blog, Beth Howell reveals the fascinating contents of an unassuming volume of poisonous and noxious plants.

Many of the Institution’s botanical volumes are the highlights of the collection. Full-bound in gilded calf, like many nineteenth-century volumes, they appear to the casual browser as worthy of extended perusal. However, around the time that I was researching my talk on ‘Why the Victorians were weird’ I found a small, faded-green volume that really broke the mould. The text declared itself:

But the humble appearance of the volume belied the treasure within.

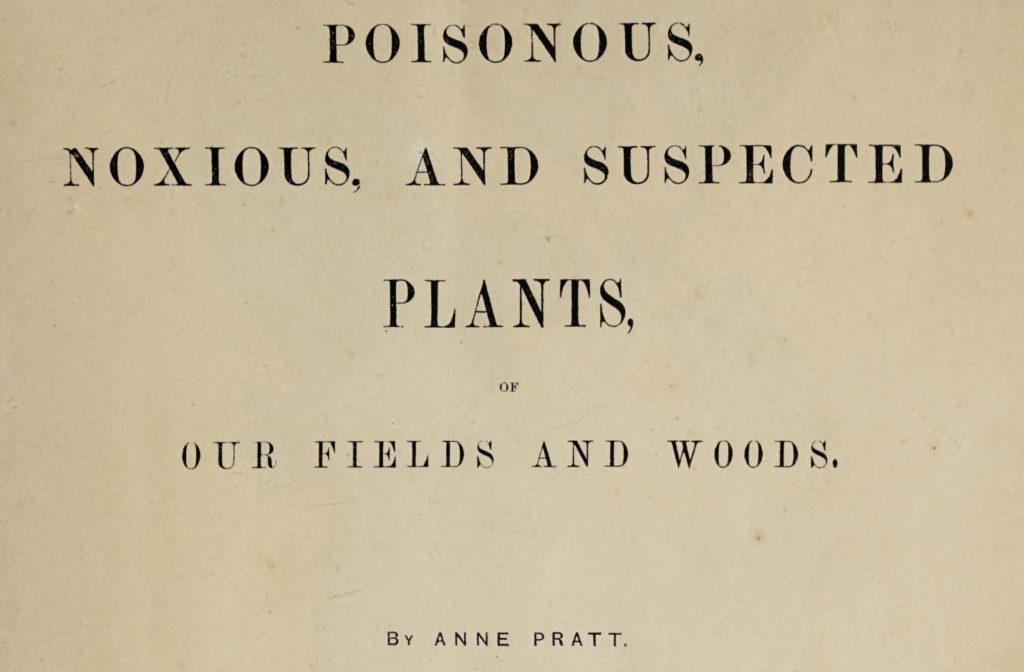

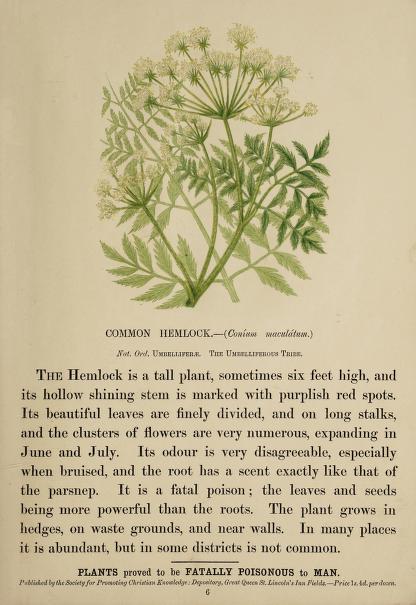

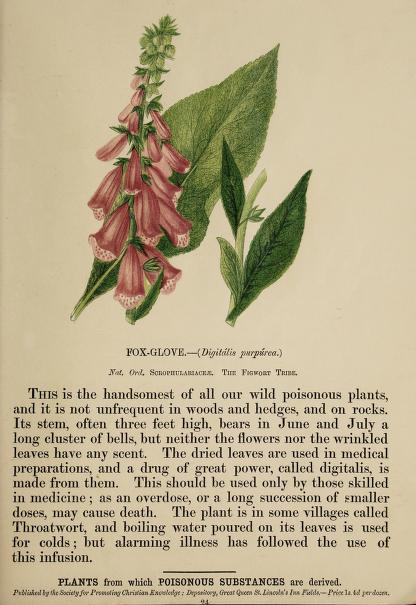

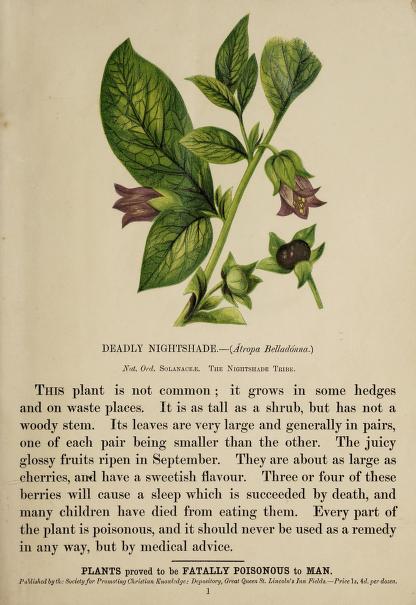

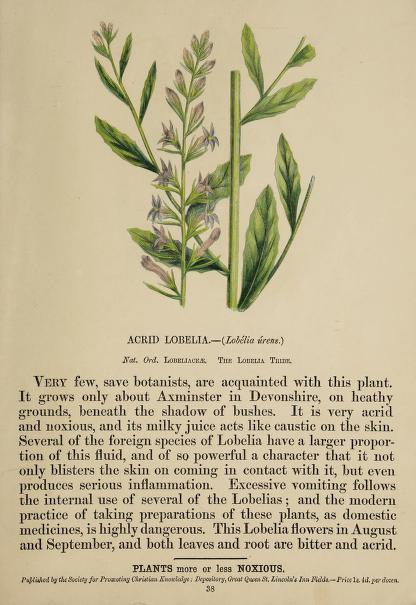

Upon opening, the book arrests its viewer with a series of stunning illustrations of plants that can cause pain and harm. Written by Anne Pratt (1806-1893) and published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge in 1857, each page presents a different specimen, complete with a full colour illustration, a short account of where the plant might be found, and an outline of the adverse effects it might cause. Identifying features, including the appearance and odour of each plant are recounted in great detail.

The ‘common hemlock’, we are told, has a ‘very disagreeable’ scent, whilst the thorn apple’s is ‘unwholesome’. Meanwhile the ‘meadow saffron’ is described as having seed-vessels ‘as large as pigeons’ eggs’, whilst the foxglove ‘is the handsomest of all our wild poisonous plants’.

The writer also makes sure to distinguish between a plant’s potential medicinal purposes as well as its poisonous properties, often concluding with the risks posed to children. Of the common henbane, she writes:

‘A valuable medicine is procured from it: but children should not play with the Henbane pods, as illness has arisen from swallowing a few of the seeds.’

The foxglove, then as now, provides a ‘powerful drug’ for the treatment of heart disease, ‘but this should be used only by those skilled in medicine’.

Educational, accessibly-worded, clearly illustrated, Anne Pratt’s mid-Victorian volume was very much in the spirit of the society that had published her work, and was both protective and didactic. Tracing Anne Pratt’s own story, however, is a little more difficult.

Anne Pratt was born in 1806 and displayed an interest and talent for depicting botanical specimens from an early age. She published her first illustrated volume aged only twenty, and went on to complete many further volumes on trees, ferns, and wildflowers. In each, her skilful rendering of leaves, stems, petals and pistils demonstrates her extensive knowledge of her subject. This, of course, would have been an education she acquired at home. For most of the nineteenth century, women were not encouraged to study science at university. Collecting and drawing flowers in a private capacity was seen as a suitably ‘feminine’ hobby for a young Victorian woman. The market for natural history publications and practices soon skyrocketed.

From the 1840s onwards, pteridomania, or ‘Fern Fever’ took hold. The novelist Charlotte Brontë kept a particularly impressive volume of pressed ferns she found during her moorland walks, but she was hardly an isolated case. Flower-pressing was a common hobby for middle-class women on a widespread scale, whilst the language of flowers, as set out in Kate Greenaway’s 1884 volume, was a well-established code. John Everett Millais drew on this language in his depiction of Ophelia (1852). As Ophelia floats down a stream bearing a posy of picked forget-me-nots, poppies, and daisies, she not only functions as a faithful representation of Shakespeare’s text, but also as a woman who has reached beyond the domestic ‘sphere’ and who accordingly risks destruction.

The art critic John Ruskin, perhaps the greatest public pioneer of separate spheres, appropriately named his lectures regarding the traditional gender roles of men and women Sesame and Lilies. For Ruskin, a woman’s place was unequivocally in the home:

‘But the woman’s power is for rule, not battle,- and her intellect is not for invention or creation, but for sweet ordering, arrangement, and decision. She sees the qualities of things, their claims and their places. Her great function is Praise: she enters into no contest, but infallibly adjudges the crown of the contest. By her office, and place, she is protected from all danger and temptation.’

When Ruskin speaks of ‘rule’ he means the domestic environment. More widely, however, his remark that women must enter ‘into no contest’ and to focus on ‘ordering’ and ‘arrangement’ rather than ‘creation’ is even more telling. A woman might ‘arrange’ a pretty book about flowers, or ‘order’ a volume based on scientific principles discovered by a man, but she must not, literally or academically, supersede her place. How far, then, might such attitudes have affected the reception of Anne Pratt’s work?

A notable twentieth-century critic and compiler of floral depictions, William Blunt, declared in his Art of Botanical Illustration (1950):

‘The plates in Anne Pratt’s The Flowering Plants and Ferns of Great Britain (S.P.C.K. 1855), a book which did much to interest the general public in British flora, are pleasantly composed, though, owing to the limitations of the newly popular technique of chromolithography, not always very accurate in colour. Anne Pratt (1806-93) was a grocer’s daughter of Strood, in Kent. The drawings which illustrate her book are her own work, though in their published form they no doubt owe a good deal to the artists of the firm of W. Dickes and Co., who redrew them on stones.

In his cursory review Blunt acknowledges Pratt’s work was popular and ‘pleasantly composed’ but doubts both its originality as well as Pratt’s skill as an artist. Instead, he suggests she owed ‘a good deal’ to the firm who printed her drawings. With a few exceptions, most artists and illustrators at the time were at the mercy of those employed to print their drawings and Pratt was certainly fortunate to have her work printed by William Dickes, a specialist in printing works of natural history. Yet, why would Pratt have owed any more to the printer of her work than any other artist? Without any supporting evidence, William Blunt infers that W. Dickes and Co. are the real creators of the book’s exquisite illustrations, not a ‘grocer’s daughter of Strood’.

However, would a woman risk her reputation by putting her name to illustrations that did not resemble substantially her own designs? Whilst flower-pressing at home was commended, printing a volume of your own drawings for public consumption certainly contradicted the Ruskinian sentiment of remaining in the domestic sphere. The Brontë sisters took pseudonyms to publish in the 1840s. Beatrix Potter would have her own task ahead to persuade Frederick Warne & Co. to print her animal stories and illustrations in 1902. It seems unlikely that Anne Pratt, still unmarried in 1855, would have wanted to risk her reputation without due cause: the promotion of her own extraordinary talent.

Whilst Pratt’s work may have been adapted slightly just before publication, she certainly had the time and space to portray a vast array of plants in the first instance. Moreover, Pratt’s less than perfect personal circumstances – which Blunt dismisses rather than considers – might in fact have been a contributing factor to the scientific intensity of her work. From a young age, Pratt developed a difficulty moving her legs and was largely housebound due to ill health. Her sister would gather and bring her plants to draw. Pratt was therefore close to her subject in two regards: there was little to distract her from keeping long hours at home drawing, and little, I suspect, to distract her from looking for a plant that might help her own predicament. It is no more of a fanciful assertion, I think, than to suggest she never really drew her designs at all.

I finish with a page from the book describing Acrid Lobelia that Pratt suggests ‘grows only about Axminster in Devonshire’. Though slightly more widespread now, it remains rare in England beyond the South West.

Beth Howell, Saturday Activities Co-ordinator

The full text of Poisonous, noxious, and suspected plants, of our fields and woods is available online here.