The Folklore of Cornwall (1975): Exploring the Tradition and Legacy of Cornish Folklore

The Folklore of Cornwall (1975)

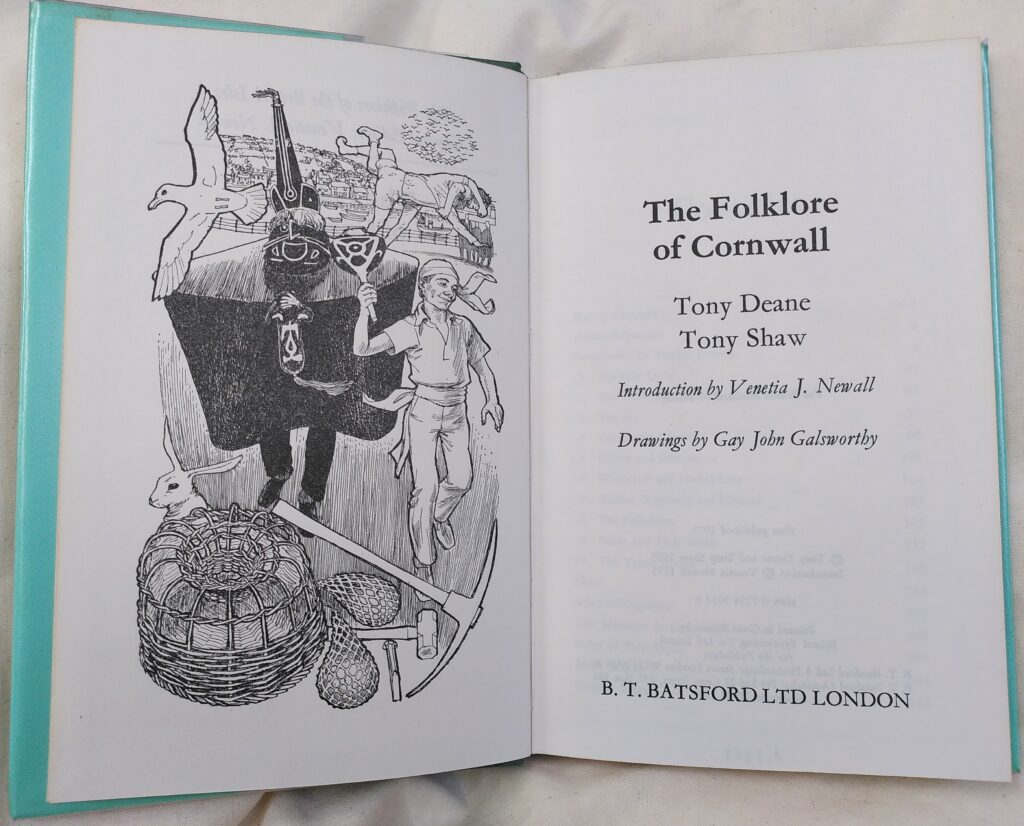

For March’s Book of the Month library volunteer Mela Moseley delves into our modern South West collection to discuss Tony Deane and Tony Shaw’s The Folklore of Cornwall (1975). Continuing in the tradition of the Victorian folklorists who first began to document the mythology of the region, Deane and Shaw combine anthropological research with engaging storytelling. The result is a detailed exploration of Cornish legend which remains a valuable resource for those interested in the subject.

Cornwall has long been a source of curiosity for those interested in mythology and folklore. Anthropological writing on the mythology of Cornwall has a long tradition, particularly from the 19th century onwards. J.T. Blight’s A Week at Land’s End (1861), William Bottrell’s Traditions and Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall (1870), and Jonathan Couch’s The History of Polperro (1871) retold old Cornish myths and legends, romanticising the landscape and its ancient tales. Meanwhile, Sabine Baring-Gould’s A Book of the West (1899) and Cornish Character’s and Strange Events (1909) blended Cornish folklore with historical fiction, capturing the mysticism of the Cornwall’s past. All these works are highlighted by Deane and Shaw in their select bibliography and can additionally be found in the DEI’s collections.

In their book, The Folklore of Cornwall (1975), Tony Deane and Tony Shaw guide the reader through the lore that shaped the identity of this region. Through a detailed investigation and engaging storytelling, they provide a captivating narrative that uncovers tales of the fairies, giants and demons, which have since enchanted generations. More recent studies, like Ronald M. James’s The Folklore of Cornwall: The Oral Tradition of a Celtic Nation (2018), owe a debt to the works of 20th-century folklorists like Deane and Shaw. I personally was drawn to this book as it reminded me of my childhood love for fairytales, particularly the Brothers Grimm. There was a gradual shift, most likely resulting from age, in which exploring folklore became less about the escapism, and more about the historical implications. Going hand in hand with my love of history – which I am currently studying at the University of Exeter – I am now more interested in why myths and legends can survive over multiple centuries, and the historical significance that can be drawn from stories like Deane and Shaw’s.

The Folklore of Cornwall highlights the enduring influence of Cornish folklore on popular culture, tracing this legacy through the works of writers, artists, and filmmakers who have been inspired by its myths and legends. From the Pre-Raphaelite paintings of King Arthur’s court to modern adaptations of Cornish tales in film and television. The authors show how Cornwall’s folklore continues to captivate audiences around the world.

Perhaps the most famous example is the legend of King Arthur which, despite a lack of substantial historical evidence tying this mythic king to the region, has become entrenched in Cornish tradition. Places which have been linked to King Arthur include the village of Slaughterbridge, as well as Tintagel Castle. Alongside various other details of regional Arthurian legend, Deane and Shaw recount the widespread notion that “King Arthur’s soul inhabits a Cornish chough” (22). The red-billed chough has long been associated with Cornwall, appearing on the Cornish Coat of Arms. According to the legend, King Arthur did not perish in his last battle, but rather migrated into the body of a Cornish chough, and the return of the chough will signal the return of King Arthur.

“Where shall we find King Arthur? His place is sought in vain,

Yet dead he is not, but alive, and he shall come again!”

The theme of return and redemption is common in folklore, symbolising the promise of a brighter future. These lines capture the elusiveness of King Arthur, which is a reoccurring theme throughout the mythology. As Deane and Shaw note, this accords with the “widespread folk motif” of the sleeping hero (23). But it also alludes to his supposed immortality, which parallels that of Jesus in the Christian tradition. The idea of immortality and the promise of return paints the King as an almost messianic figure, and Deane and Shaw write that “it is no exaggeration to say that, through the centuries, King Arthur has been regarded with quasi-religious enthusiasm” (26).

Deane and Shaw write that, for the Cornish people, the phrase “he shall come again” was a rallying cry which “served, for a thousand years of national extinction, to help keep alive the county’s sense of separate entity” (23). Myths often form the foundations of shared cultural identity: through shared narratives and experiences, social cohesion is fostered. The desire for the restoration of the ideals of chivalry, justice and unity are central to folklore and legends, and Cornish mythology remains a unifying force to this day.

One of the book’s most compelling aspects is its exploration of the diverse cast of characters that populate Cornish folklore. From the mischievous fairies and giants that inhabit the moors to the legendary figure of King Arthur, Cornwall’s folklore is teeming with colourful personalities whose stories reflect the region’s rich cultural tapestry. The story of Anne Jeffries stands out, particularly in relation to Arthurian myth. Jeffries, who was born in St. Teath in 1626, claimed to have encountered fairies for the first time when she was nineteen. The meeting

“left her with the power to heal by touch. She could cure broken bones and such

diseases as the falling sickness… Anne was supposed to have spoken and

danced with the fairies and to have been fed by them for long periods.”

Anne’s story in relation to Cornish fairy folklore, discussed in Chapter 4, is used by Deane and Shaw show how myths spring from the unbelievable, the unattainable and the uncontrollable. If legends were plausible, they would not be remembered and passed down through generations: the sense of intrigue and disbelief must be strong enough to consistently spark curiosity. Unfortunately for Anne, she was later accused of witchcraft, showing the underlying fear instilled in society, and crucially, the conflict between local folklore and the repressive authority of Church and State in old Cornwall. Despite Anne’s healing abilities mirroring those of Jesus, fear towards the supernatural nevertheless outweighed the hope of supernatural relief at a time when life was hard, and “poverty and hunger were never far away” (47).

“Cornwall has many tales of men, women and children being transported to a

beautiful subterranean fairy world”

Fairy stories bridge the gap between realism and fantasy. It seems funny to modern day audiences, as we would view witchcraft along the same vein as myths about fairies and giants. It shows that past societies, even when trying to be logical, were dominated by ideas arising from superstition and folklore. Fascinatingly, Deane and Shaw also show that these beliefs were not limited to children or the uneducated. For example, the case reported in the West Briton in 1843, of a couple in Penzance who were mistreating their son because they believed he was a changeling (93). Additionally, the reference to the boy being mistreated by the servants as well suggests that this was a fairly wealthy family. This highlights the idea that mythology also subverts class divisions, making it accessible to everyone, regardless of social status or hierarchy.

They are not synonymous with our current fairytales, which suggests that myths were written in truth – or at least – this is the truth recognised by the authors of the time. The elevation of the supernatural is a recurrent theme in The Folklore of Cornwall, and reveals the societal dynamics towards morality, religion and the natural hierarchy. There is a difference between the way in which we in the 21st century engage with myths, and the meaning these stories held for people living in past centuries, when science was less advanced, and access to education and medicine was more limited. Underdeveloped communication and transportation networks made rural areas like Cornwall far more isolated than they are today. This partially explains why places like Cornwall were so susceptible to tales of the supernatural.

The Folklore of Cornwall is a masterful exploration of the rich tapestry of myths, legends, and traditions that define this enchanting region. Deane and Shaw offer readers a comprehensive overview of Cornwall’s folklore, shedding light on the characters, landscapes, and customs that have shaped its cultural identity. For anyone intrigued by the magical world of Cornish folklore, this book remains an indispensable guide.