Feeding the Victorian Invalid: Sarah Sharp Hamer’s Diet and Cookery for Common Ailments (1894)

For January’s Book of the Month our Library Assistant Fiona Schroeder discusses Sarah Sharp Hamer’s Diet and Cookery for Common Ailments (1894). This interesting volume, written under the pseudonym ‘Phyllis Browne’, provides a valuable insight into ideas about food and illness in the 1890s, and the popularisation of nutritional science during this period. Hamer’s book bridges the gap between works on cookery and domestic economy, and scientific writings on food chemistry, nutrition, and health. As such, it holds a unique place within the DEI’s Heritage Collection.

In the nineteenth century, expanding book markets created new opportunities for women to make a living by writing non-fiction, though they were often restricted to domestic subjects. For example Isabella Beeton, though not a regular cook herself, built a successful career as a journalist and editor for The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine and the author of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861). The author of Diet and Cookery for Common Ailments was also a professional writer, though not as well-known as Beeton. Sarah Sharp Hamer (1839-1927) published several books on home economics and cookery under the name ‘Phyllis Browne’, including A Year’s Cookery (1879), The Girl’s Own Cookery Book (1882), and The Dictionary of Dainty Breakfasts (1898). As ‘Olive Patch’, Hamer also wrote novels for younger readers. Most of her works were published by Cassell & Company, who specialised in popular fiction and reference texts. Her cookery books appear to have been moderately popular; an advertisement for A Year’s Cookery included in the 1894 edition of Diet and Cookery for Common Ailments shows that this earlier work was, by that time, in its twenty-second thousand printing. Of course, this bears no comparison to Beeton’s best-seller, which sold 60,000 copies in its first year.

What distinguishes Diet and Cookery for Common Ailments from other Victorian cookery books is its mixed focus on both cookery and nutritional science. The title page gives precedence to Hamer’s anonymous co-author, “A Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians”, subtly establishing the book’s scientific credentials. It is uncertain whether this physician was a real contributor, or a fiction used to bolster Hamer’s authority in writing about health, at a time when women were still largely excluded from the medical profession. Real or not, the advertised collaboration between medical expert and home-economist accords with the central aim of the text: to bridge the gap between the scientific and domestic spheres, bringing recent discoveries in the fields of organic chemistry, physiology and dietetics to bear on the nursing duties which might fall to a middle-class housewife. As Hamer writes in her prologue:

“This book is intended to serve as a practical dietetic guide to the invalid, and in its pages, it is hoped, the reader will find the food problem stated, not merely in terms of carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen … but in the form of actual dishes which will prove both digestible and palatable”

The first chapter is largely scientific. It describes the different substances found in plant and animal tissues, explaining the part played by each in furnishing the human body with “the means of maintaining life”. The understanding of food as being composed of carbohydrates, hydrocarbons, proteids, salts and water had grown out of Justus von Liebig’s work on organic chemistry in the 1840s, and particularly his Researches on the Chemistry of Food (1847). Vitamins were notably absent from the discussion at this point: Vitamin A, the earliest of these, was only discovered in 1913. Nevertheless, by the 1890s an approach to nutrition had emerged which largely remains with us to this day. This posited that the body needs these substances, in the correct ratios, to function normally. As a result, metaphors which figured the human body as machine, and food as fuel, became prevalent during this period. For example, Beeton writes that “it would be as reasonable to expect a locomotive to run without plenty of fuel as expect the human body to perform its daily labour without a sufficient supply of suitable food”. Through such imagery, the mysteries and complexities of disease were presented in reassuringly simple terms; medicine was reframed as mechanics. The implication that food might have the power to heal was appealing, particularly as medicines prescribed at the time often did more harm than good. In Sydney Whiting’s satirical Memoirs of a Stomach (1854), the narrating organ rails against the various “poisons” prescribed to cure his dyspepsia, which include opium, bismuth, ammonia, aluminium sulphate, sulphuric acid, and potash. He advocates for moderation, mastication, a careful choice of food, regularity of meals, exercise and the abjuration of physic as the surest means of restoring health. While giving due deference to the medical profession, Hamer also asserts the importance of food, writing that “drugs have their place … but diet in all cases takes precedence”.

Having described the chemical, biological, and physiological processes underlying human nutrition, Hamer moves on to discussing the feeding of invalids specifically. Her second chapter presents the reader with an ascending scale of foods, which progresses from a limited “slop dietary” all the way to “the full dietary of the healthy adult”. This scale begins with milk – a “complete food”, and one of the articles of diet which are most easily borne. “If you are in doubt,” writes Hamer, “give milk: this is a safe doctrine”. As the patient convalesces, milk can be supplemented with beef-tea, and other meat broths. Hamer considers “three pints of milk and a pint of strong beef-tea” as sufficient food for an adult invalid. To provide additional nourishment, the assiduous nurse might administer a “supplemented beef-tea”, to be prepared thus:

“Beef-tea may be made in the ordinary way, and then to this fluid we may add varying quantities of raw meat which has been reduced to the finest pulp … With the addition of a little salt, such an admixture is very palatable, the taste of the raw meat being effectually disguised. The beef-tea, when the meat-pulp is added to it, must not be very hot, or the albumen of the pulp will be coagulated, but it may be warmed: the mixture is very suitably taken cold or iced. … The stimulant effects of such supplemented beef-tea would be first felt, and upon this would follow the assimilation of the meat.”

To modern readers the idea of beef-tea fortified with raw beef pulp, served lukewarm or iced, probably seems somewhat repulsive, and not particularly wholesome. But Hamer’s enthusiastic endorsement is reflective of contemporary thinking about meat, and particularly beef. This had long been regarded as a vital source of imperial Britain’s national strength. As early as the 1730’s, Henry Fielding’s popular ballad “The Roast Beef of Old England” had celebrated the titular dish as one which “ennobled our veins and enriched our blood”. In the late-nineteenth century, there was widespread concern that the country’s increasing reliance on potentially inferior, imported meats posed a threat to the English stamina. Meanwhile, vegetarian activists like Henry Salt stridently opposed the popular belief that “meat alone can give strength”, arguing that flesh-foods were, in fact, dangerously over-stimulating, and encouraged vice and violence. Even when speaking from opposing sides of the question, there seems to have been a consensus among commentators that, for better or worse, meat has a powerful effect on the human body. In line with such thinking, Diet and Cookery presents beef as the ultimate food, a quasi-medicinal substance which can revive and strengthen an invalid in their weakest state.

As they prepare to transition out of the “slop” phase, Hamer recommends the patient next be given eggs – raw or lightly boiled are the most digestible. All being well, they could then be allowed some boiled white-fleshed fish – or the ministering nurse might wish to try the effect of raw oysters. At this stage, small meals at definite intervals will become allowable. These might consist of milk puddings, boiled custard, jellies, thin dry toast made from white bread, and sponge-fingers, taken with water or weak cocoa. Next, meat may be introduced: first poultry, beginning with white-fleshed birds; then mutton, followed by the more stimulating beef. Hamer deems pork, venison, and salted meats as wholly unsuitable for invalids.

Finally, the discussion turns to Vegetables. These, writes Hamer, require “vigorous digestive powers”, and should thus be last thing to be reintroduced into the invalid’s diet. When they are admitted, it must be “in great moderation”. Pulses and root vegetables are “decidedly indigestible” and should be excluded, but plainly boiled green vegetables like broccoli, Brussels sprouts, celery and lettuce, may prove wholesome. Of all vegetables, potato may be given first, and roasted potato is best. However, Hamer cautions, “potatoes vary much in size, and to allow “roast potato” does not imply consent to a whole potato”. Fruits are generally not recommended for invalids, though peeled and deseeded grapes, or a baked apple, may be allowed on occasion. Nuts are harmful, and absolutely prohibited.

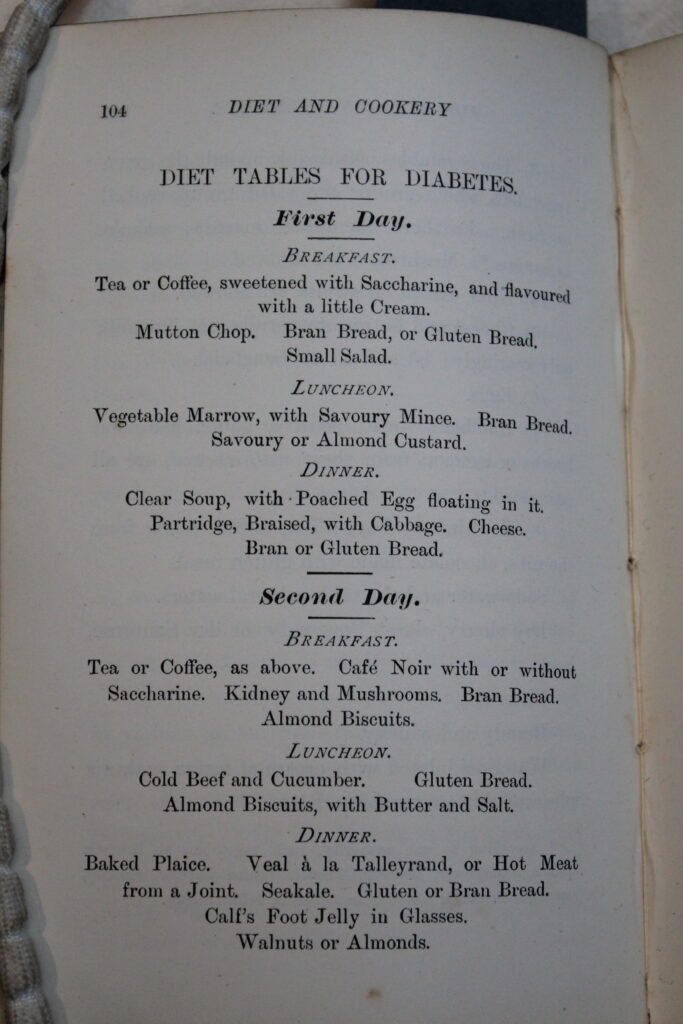

As well as setting out a general procedure for feeding invalids, Hamer’s book provides diets tailored to specific ailments, complete with two-day meal plans. Some are diseases which seem to belong to the past: menus are given for those suffering from gout and consumption, and while Hamer does not prescribe any fixed diet for “nervous prostration” – this being an affliction which manifests in a variety of ways – she does recommend “feeding up”, and the provision of liberal quantities of meat to ensure that the diet is sufficiently stimulant (readers might here refer to her earlier assertion that milk and beef-tea make an excellent diet for “grave states of depression”). Hamer also provides diet tables for conditions still prevalent in the twenty-first century, such as obesity and diabetes. The latter is particularly interesting. It recommends the use of Saccharine – a sweetener derived from coal-tar, discovered in 1879 – as a substitute for sugar, and “bran bread” or “gluten bread” instead of regular wheat bread. In this we can see commercial processed and synthetic foods beginning to enter the British diet, as well as the advent of replacement ‘health’ foods and supplements.

Diet and Cookery for Common Ailments certainly presents a curiosity for twenty-first-century readers. Some of Hamer’s ideas about nutrition and health now seem bizarre, and one might wonder how anyone in the Victorian period ever recovered from illness on a slop-diet of milk and beef-tea. However, as we continue to see a steady increase in the prevalence of diet-related diseases, particular in Western societies, the holistic approach exemplified by this book, in which nutrition is acknowledge as a key contributor to human health, is undoubtedly still valuable today.