Captain John Cooke: ‘a public character and John Bull tradesman’

Amber Flood has written about some works relating to Captain John Cooke for February’s Book of the Month. This piece focuses on Cooke’s 1819 pamphlet titled “Old England For Ever” and a satirical pamphlet that was printed in response titled “Old England For Ever continued.”

John Cooke was born in 1765 in Ashburton at the Rose and Crown public house which was owned and run by his father. He is perhaps best remembered as the Captain of the Exeter Javelin Men, an important office at the Assize. To his contemporaries in the early nineteenth century, he was also known as a saddler and pamphleteer who used to stick notices on the wall outside his business. When he was young, he was apprenticed to a saddler in Exeter named Chaster. Cooke succeeded the role upon Chaster’s death in 1786 and became well known as a skilled saddle maker and was employed by local members of the gentry such as Lord Rolle, Sir Thomas Acland, Sir Stafford Northcote amongst others. This pamphlet, and its pseudonymous response, provides a snapshot of the tensions that existed in England at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Following the revolutionary period there were palpable anxieties about the situation in Ireland, with ideological disagreements over catholic emancipation, and the toleration of religious dissent more generally. Additionally, the class system had taken a new shape as professional and industrial elites became more firmly established as the ‘middle class.’ New social classifications surfaced issues surrounding who should be able to vote in elections, leading to what has been called the ‘Age of Reform’ where a series of political reform movements occurred. This pamphlet also demonstrates where Exeter sat within a national framework of urbanisation, which the southwest in general had lagged behind. Additionally, Cooke’s pamphlet exudes national pride at the expense of other nations and caricatures the attitudes that existed towards the end of the Georgian period when the Abolitionist movement was a prime concern.

As the title of his pamphlet suggests, Cooke was devoted to his country, and he hoped to see a return to traditional English values. For him, this involved committing yourself to your city, county and in turn, your country. In this pamphlet, he provides an extensive list of ways he has enriched the city of Exeter and, to use a twenty first century colloquialism, he name-drops a number of Exeter notables who he came into contact with. He asserted throughout the text that he was writing in a selfless manner, and that he, as a devoted citizen of the city of Exeter, hoped to be a positive example for others. The satirical pamphlet published anonymously in response titled “Old England For Ever (continued)” illustrates that some citizens had not interpreted it in this way. The response is written in the first person, and parodies the self-flattery and patriotism exhibited in Cooke’s pamphlet by positioning him as the narrator.

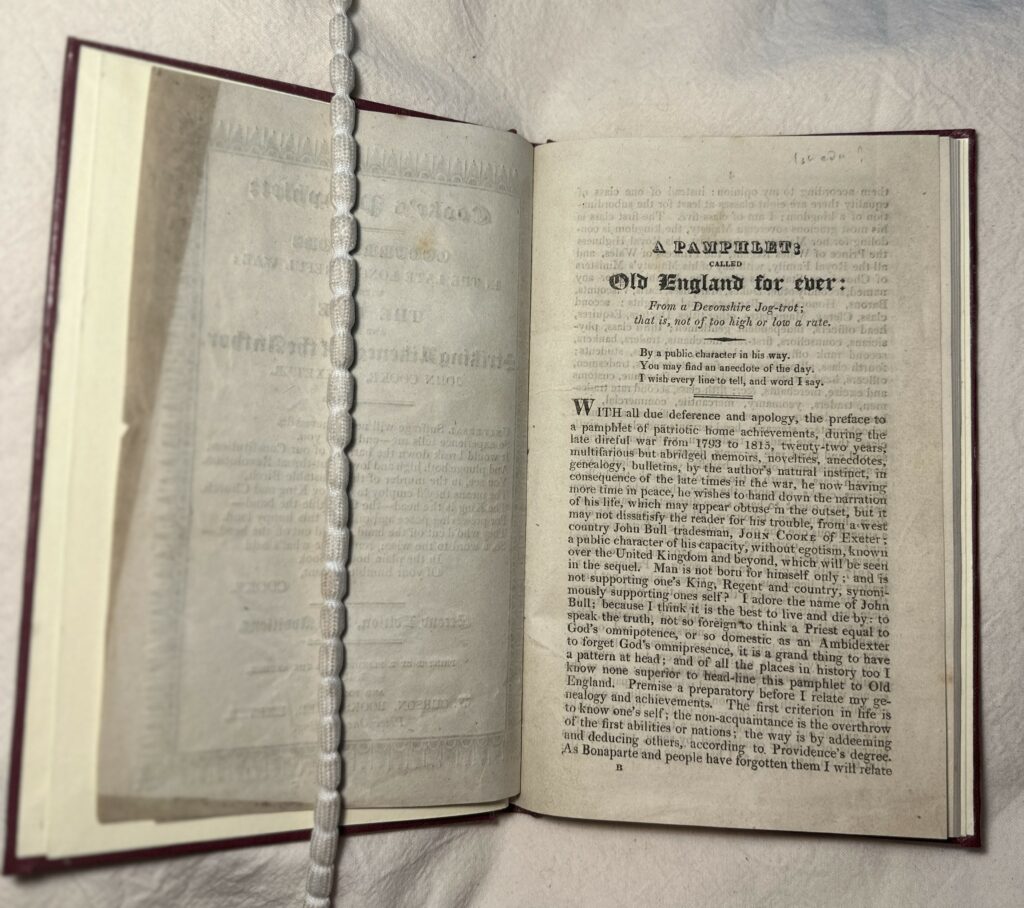

“Old England For Ever” by Captain John Cooke (1819).

Cookes “Old England For Ever” serves as a love letter to the ‘old order’, to ‘old England’ and to himself. It also reveals ostensible anxieties about the changes he witnessed in English society throughout the course of his life. As a staunch loyalist, it is apparent throughout this pamphlet that Cooke is disturbed by republicanism. He mitigates these concerns by comparing the achievements of his country against what he considers to be the pitfalls of others. At many points throughout this pamphlet, Cooke breaks into rhyme, a practice which his adversaries criticised greatly. For Cooke, working hard within your trade or profession was an act of loyalty to your country. He expressed this in a rhyme after providing details about his career as a saddler, and those individuals who he had served:

I sticked to my King, leather and tools;

And for order wrote a set of shop rules.

It’s not what work is brought for to be only done,

Every think that’s necessary, buckle or tongue;

For instance, a saddle is brought to stuff, that’s all,

A stirrup-bar is wanted to prevent a fall;

All your work must be done well, not like fools,

For if it breaks on the road, there’s no tools.

Working with the hands only is but part,

The head’s the essential to make work smart.Be John Bulls, true to your country and Church,

Always tell the truth and don’t never lurch.

Many of the people that had supposedly supported his business were members of the nobility such as John Rolle, Edmund Granger, Henry Ley, Thomas Acland, and many more. Cooke most likely mentioned these names in hope that it would raise his own profile, garner support from those he mentioned, and legitimate his claims as a John Bull. He describes Sir John Acland for example as the ‘rising sun of Devon.’

Image can be seen on display in the Devon and Exeter Institution.

After detailing his early career, he continues to list his ‘sixty home achievements during the late war, for [his] king and country.’ He wrote that besides his own business, one of his priorities was to ‘bring trade to Exeter’ which, he believed ‘had been a century behindhand in her improvement’ when compared with the rest of the country. He then notes all the ways Exeter had nonetheless been loyal to the royals. Likewise, to the manner in which he compared England to other countries in Europe, Cooke identifies Devon as superior in character to other counties since there had been ‘but one small riot in Devonshire to its honour and credit’ which was ‘stopped in its infancy.’ He notes how he selflessly published handbills ‘at his own expense’ hoping they would supplant ‘inflammatory pamphlets as Tom Paine’s.’ When Cooke spoke of a vote that was taking place in the Guildhall during the first year of the French Revolution, he described the taunts he received from his adversaries such as when a man named Sergeant Pell asked him ‘are you not a Frenchman? I said, a Frenchman! No, sir, I am a true John Bull. He said, of the calf kind. I said, it must be a calf before it’s a bull. The Sergeant sat down.’ He also writes of his philanthropic contributions to Exeter. In 1800, when the ‘poor grumbled, noisy, clamorous in the market’ he bought 500 potatoes from the country and sold them at a loss. It is clear throughout this autobiographical pamphlet that Cooke fancies himself as a benevolent and feels he has not been given the credit he deserves.

In writing about Exeter, as the city of ‘the second county’ of England, he asserts a superiority about his locality by way of comparison with others. He does the same on an individual level by describing his achievements as aspirational, in opposition to the behaviour of others who he disagrees with ideologically. Cooke also writes disparagingly of his religious and racial other. With regards to the former, he writes disapprovingly of ‘every Catholic of England or Ireland’ due to the fact that they acknowledged ‘no King superior to their Pope’ which for him as a loyalist proved difficult to digest. He specifically refers to the Irish in this regard, stating that he wished they had ‘as good poor laws as England’ and were ‘as quiet as England and Scotland’ for it pained him to hear about their ‘dreadful depredations and murders.’ He asserts that the nobility there should eradicate ‘priestcraft’ and ‘Romish barbarism’ which, for him, was more important than Catholic emancipation. As we approach the end of the pamphlet, Cooke lists what he perceived to be the positive outcomes of the Napoleonic wars which include property tax, education of the poor, and moral improvement. He also refers to the abolitionist movement here and chooses to elevate the position of English people by stating, in quite a derogatory manner, that enslaved people did not ‘work as hard as our smiths.’ His intention throughout this text is to raise the profile of his country and in turn, himself, as he demonstrates his efforts at upholding the values of traditional ‘Old England.’ He even went as far as to name his residence ‘Waterloo Cottage’ to prove his devotion, and signed off the pamphlet stating that he, ‘a Devonshire jog-trot’ has ‘done enough to be termed a character in his way; a John Bull tradesman.’

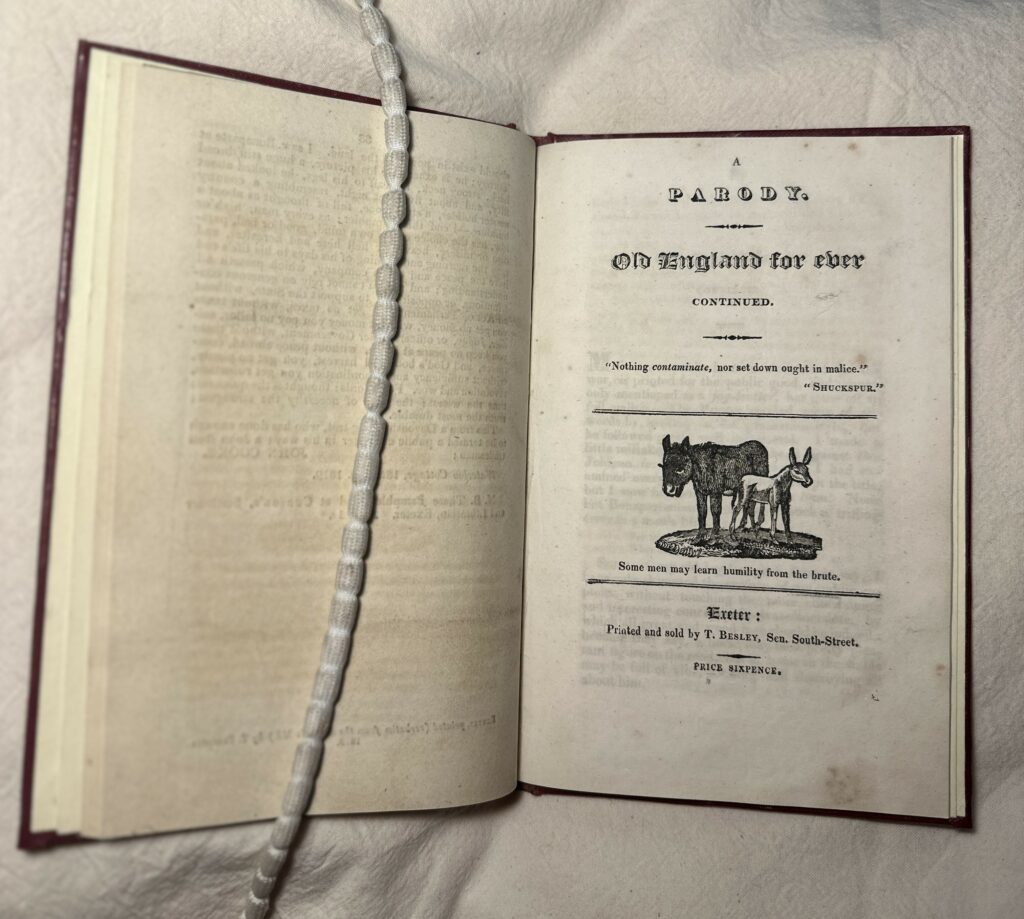

Title page of “Old England For Ever” published anonymously in Exeter.

The anonymous response “Old England For Ever Continued” is a parody which is set out as a continuation of his autobiographical account. The title page references a quote from Othello by ‘Shukspur,’ the misspelling of which is clearly a jab at Cooke’s poor use of grammar. He is mocked about his grammar throughout the pamphlet, as well as his tendency to associate himself with renowned writers such as Ben Jonson. In Cooke’s original pamphlet, he uses lots of horse metaphors and imagery which is mirrored in an exaggerated way in this reply. This pamphlet also comments on how disordered and inconsistent the structure of the original one was when it states, ‘here follows my thoughts upon Marriage, Courtships, Hard Suppers and Death.’ It also insults him throughout by portraying him satirically as brutish and lacking in the qualities of a gentleman. This is done through the narrator, Cooke, vindicating himself against accusations of being incontinent in public spaces. It also points to the ways in which he has been reformed as a person through detailed descriptions of his previously unsophisticated manner. It is evident that the writer does not believe this to be the case, as they continuously refer to Cooke as a ‘tradesman’ which is intended as an insult. The narrator, as Cooke, goes as far as to state that he is ‘ready at any time to sit for [his] picture’ and that he wants to live to see his own funeral, which would prove to have a much larger occasion than that of his opponent, the printer, Andrew Brice. The pamphlet also jeered at the original’s references to Ireland, religion, and his position as Captain of the Javelin Militia, which undoubtedly aggravated Cooke, but this mockery is really hammered home at the end, when it states that he would like to be buried at Waterloo Cottage so he could have ‘constant prospect of the improvements of the city, which my bulletins have occasioned.’ This snarky remark alludes to the self-admiration exhibited throughout Cooke’s own pamphlet regarding his contribution to Exeter’s improvements. The sheen of selflessness that Cooke ironically brags about throughout his text, along with his declarations of national pride, is finally reinforced in the sign-off which states that the pamphlet was printed ‘pro-bono publico’ and that all profits would go to the Waterloo fund. These two pamphlets therefore provide a rare snapshot into the attitudes that existed as England approached a period of transformation. Cooke’s pamphlet highlights the grievances that some people had about such changes, while the response illustrates how writing about oneself in such an egotistical manner was beyond the pale of acceptable behaviour.

Amber Flood is a doctoral researcher at the Devon and Exeter Institution and the University of Exeter. The archive of the DEI will form a major part of her research on the social history of Enlightenment subscription libraries 1750-1914.

Primary references:

Cooke, John. “Old England For Ever” (Exeter: printed by T. Flindell), 1819.

Anonymous. “A Parody: Old England For Ever Continued” (Exeter: printed and sold by T. Besley).

Further reading:

Considerations on political reform and anxieties were informed by works such as Matthew Roberts, Political movements in Urban England, 1832-1914 (London, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2009) and Susie Steinbach, Understanding the Victorians: Politics, culture and society in nineteenth-century Britain (London: Routledge, 2017). More information on accepted modes of behaviour can be read in Stephen Banks, A Polite Exchange of Bullets: The Duel and the English Gentleman, 1750-1850 (Suffolk, Boydell & Brewer, 2010).

There is an illustration of John Cooke on display in the front room of the DEI with some more information.