Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) and his Library of Congress

The third President of the United States of America is best known for drafting the Declaration of Independence that galvanised the British colonies in their fight to become a new nation. At home he immersed himself in science, engineering, architecture and book collecting – even rescuing one of the world’s greatest libraries.

In 1797 Thomas Jefferson was appointed President of the American Philosophical Society:

I feel no qualification for this distinguished post but a sincere zeal for all the objects of our institution and an ardent desire to see knowledge so disseminated through the mass of mankind that it may at length reach even the extremes of society, beggars and kings.

(Acceptance speech, American Philosophical Society, 3 March 1797)

Throughout his Presidency of the Society, Jefferson championed the advancement of Enlightenment ideas; he considered knowledge in general, and science in particular, to underpin democracy and freedom:

We have spent the prime of our lives in procuring [young men] the precious blessing of liberty. Let them spend theirs in showing that it is the great parent of science and of virtue; and that a nation will be great in both, always in proportion as it is free.’

(Letter to Dr Willard, President of Harvard University, 24 March 1789)

Benjamin Franklin founded the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia in 1743 for the purpose of ‘promoting useful knowledge’; Jefferson furthered its interests in agricultural engineering, technology and manufacturing and other such strands of ‘useful knowledge’ to boost the economy and thereby to encourage a strong and independent United States of America.

Books were key to acquiring and disseminating knowledge and Jefferson claimed to have ‘a canine appetite for reading’. (Letter to John Adams, 17 May 1818). He amassed around 10,000 volumes in the library at Monticello, his neoclassical plantation home in Charlottesville, Virginia. It was the largest personal collection of books in the country. Jefferson took pains to classify and catalogue his collection, arranging it chronologically by subject according to Denis Diderot’s system of knowledge expounded in his famous Encyclopédie: History (Memory), Philosophy (Reason) and the Fine Arts (Imagination). A keen designer and inventor, Jefferson even devised a revolving bookstand able to accommodate five open books simultaneously – the forerunner of the modern computer desktop. The prototype, made by workers on his plantation, remains on display at Monticello.

In 1800, as part of the move of the new government from Philadelphia to Washington, President John Adams approved an act to provide $5000 to furnish a library of books for the use of Congress. Two years later, Jefferson made the role of Librarian a presidential appointment – a clear statement of the importance of the Library to the workings of government. (In 2016 President Barack Obama appointed Carla Hayden as the 14th Congress Librarian – the first woman and the first African American to lead the Library of Congress.)

In 1814 British troops launched an attack on Washington and destroyed the Library of Congress. Jefferson immediately offered his own magnificent library of books as a replacement: ‘there is in fact no subject to which a member of Congress may not have occasion to refer’. Congress agreed to purchase 6,487 volumes at a price of $23,950. Jefferson began to arrange and number his books and sought the service of a Georgetown bookdealer, Joseph Milligan, to supervise the packing and transportation of the books from Monticello to Washington:

… it requires a character acquainted with books, to receive the library. I am now employing as many hours of every day as my strength will permit, in arranging the books, and putting every one in its place on the shelves, corresponding with its order in the catalogue, and shall have them numbered correspondently. This operation will employ me a considerable time yet. Then I should wish a competent agent to attend, and, with the catalogue in his hand, see that every book is on the shelves, and have their lids nailed on, one by one, as he proceeds. This would take such a person about two days; after which, Dougherty’s business would be the mere mechanical removal, at convenience …

(Letter to President James Madison, 23 March 1815).

Modern-day conservators would be impressed with Jefferson’s efforts to protect his precious books during transit. He even suggested ‘covering the books with a little paper, (the good bindings at least,) and filling the vacancies of the presses with paper parings’ to cushion the books on the journey.

Sadly, another fire – accidental, at least – destroyed nearly two-thirds of Jefferson’s books in the Library of Congress in 1851. Meanwhile, however, Jefferson had employed a scholar and bibliophile, George Ticknor – ‘the best bibliograph I have met with’ – to re-stock his library at Monticello:

Mr. Ticknor … very kindly and opportunely offered me the means of reprocuring some part of the literary treasures which I have ceded to Congress, to replace the devastations of British Vandalism at Washington. I cannot live without books. But fewer will suffice, where amusement, and not use, is the only future object. I am about sending him a catalogue, to which less than critical knowledge of books would hardly be adequate.

(Letter to John Adams, 10 June 1815)

Ticknor travelled to booksellers across Europe to purchase copies of Jefferson’s favourite books – for example, ‘German editions of Homer, Virgil, Juvenal, Aeschylus and Tacitus’ – as well as several new titles.

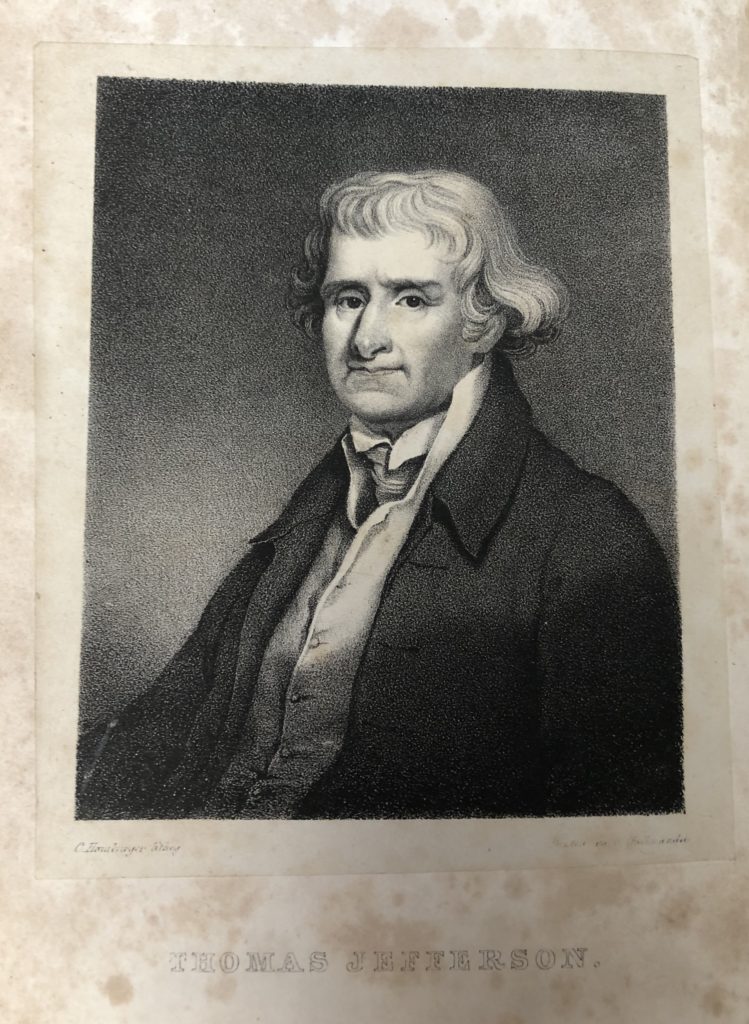

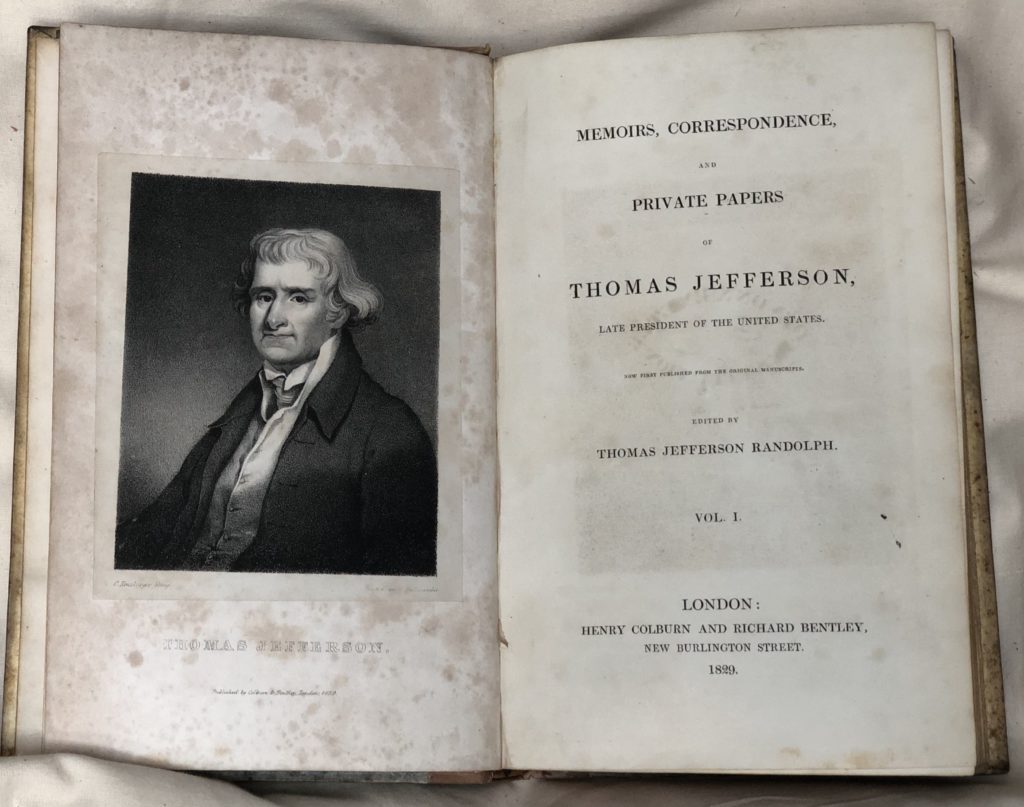

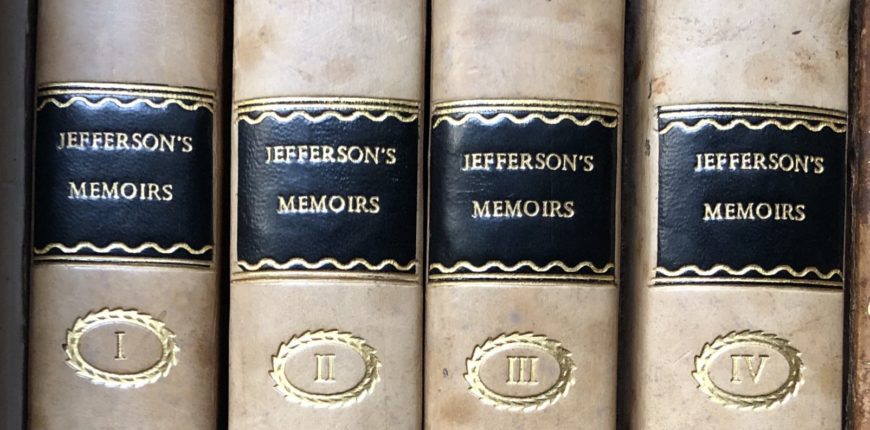

In 1829, Thomas Jefferson Randolph edited his grandfather’s papers in four volumes, published in Charlottesville by Frank Carr and in London by Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley. The volumes contain only a selection of the body of writings produced by Jefferson, carefully edited, but although his reputation has ebbed and flowed over the last two hundred years, the legacy of his passion for learning and libraries continues. He died on 4 July 1825 – the 50th anniversary of his Declaration of Independence.

The Devon and Exeter Institution has a first edition of the 1829 London printing; all four volumes are available to read online here.

Emma Laws, Director of Collections and Research