The forgotten novels of William Edward Norris (1847-1925)

In his day, W. E. Norris was described as the ‘Gainsborough of English novelists’, an heir to Trollope and a writer of ‘Disraelian intensity’ … so why aren’t we reading his novels today?

My undergraduate exam paper on Victorian Literature required me to answer four essay questions, each on a different author or authors from the course syllabus. If any questions were unexpectedly tricky, there was usually always a final ‘catch-all’ question – something along the lines of, ‘Suggest why an author who was not included in the syllabus this year ought to be included next year’. Twenty-five years on, I cannot recall if there was a course on Edwardian Literature but I imagine if there was, W. E. Norris would not have been on the syllabus. It wouldn’t be too hard to make a case for Norris; he was both prolific and very popular. Yet, how many of us have heard of him today or read one of his many novels?

We know little of the life of William Edward Norris. A Devonian, he was born on 18 November 1847 and died on the 20th November 1925 at his home in Torquay. He was the son of Sir William Norris, formerly Chief Justice of Ceylon. Following an education at Eton, Norris studied law and was called to the bar in 1874, but never practised. According to some sources, he played golf. On his death, Norris was described as a bachelor but he had married Frances Isobel Ballenden (1849-1881) on 22 April 1871; a daughter, Edith, was born the following year. Frances died on 19 February 1881 in Pau in the south of France; Norris and his daughter lived in Torquay at Underbank while his sister and her husband purchased the grand house, Bishopstowe, situated between Torquay and Babbacombe.

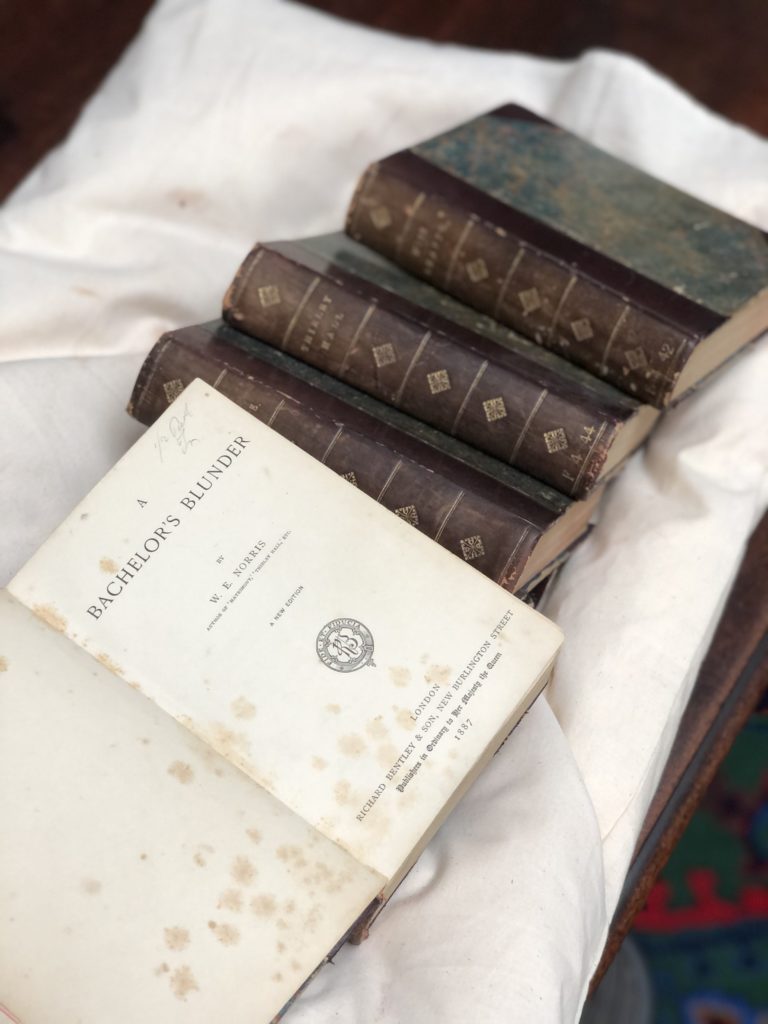

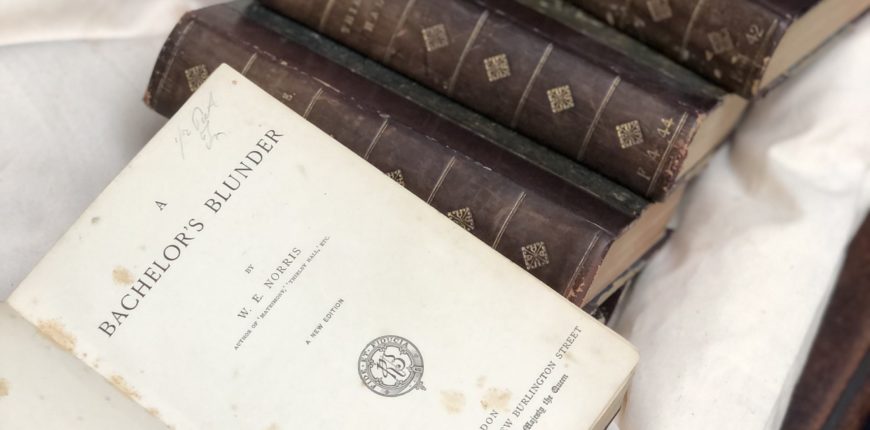

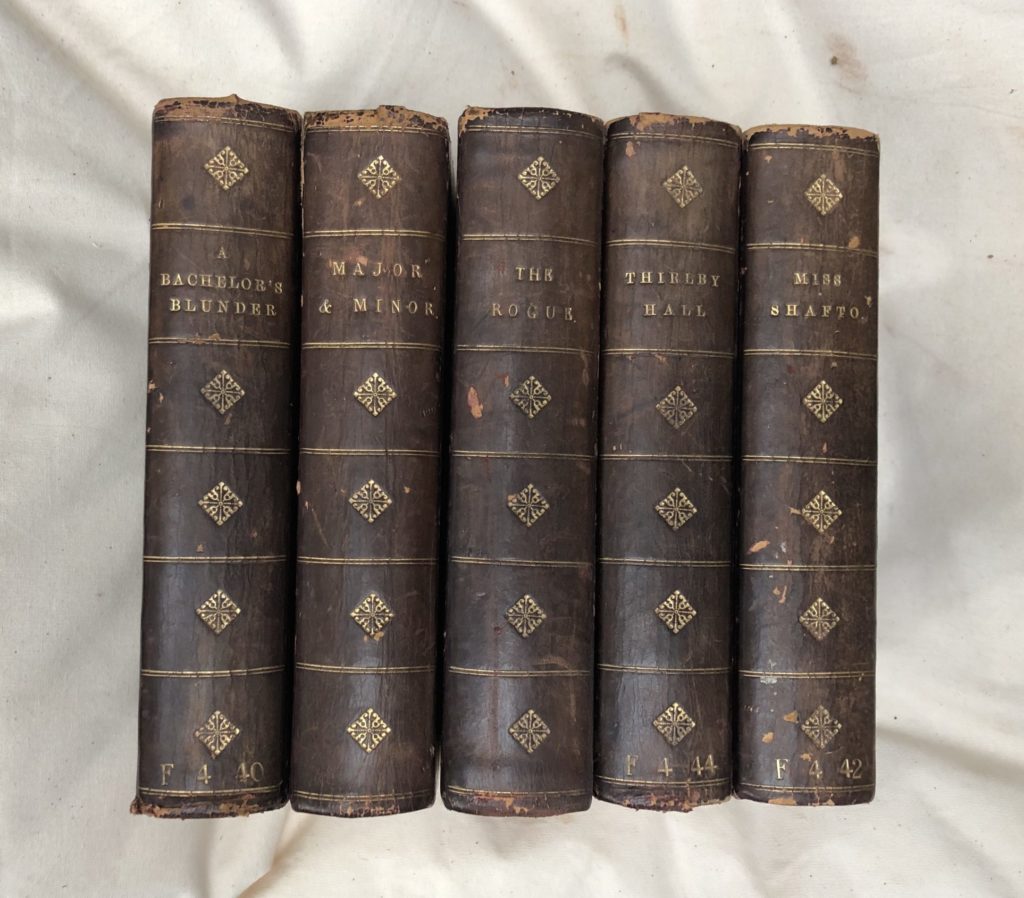

I recently discovered a small run of W. E. Norris’s novels in the Literature section in the Outer Library at the Devon and Exeter Institution. The titles date from Norris’s early years as an author; they were probably acquired soon after publication and, like many of the Institution’s 19th century volumes, are half-bound in morocco with marbled paper boards. They remain in their original location with their shelf-marks stamped on the spines. Evidently, the Institution did not continue to collect Norris’s novels, but historic library and museum collections rarely strive to be comprehensive and, in any case, literature was not prioritised in 19th century libraries.

W. E. Norris began publishing stories in 1875 in magazines such as The Cornhill and Littell’s Living Age and continued to write for magazines and periodicals throughout his career. Meanwhile, he published over sixty novels and five story collections. Wikipedia itemises all in an impressive, if somewhat tedious list.

It may be rather unfair to judge a book by its cover, but we can get a sense of the type of stories W. E. Norris wrote from their titles: Matrimony (1881), My Friend Jim (1886), The Despotic Lady (1895), The Widower (1898), Marietta’s Marriage (1897), His Own Father (1901), Lord Leonard the Luckless (1903), Not Guilty (1910), Proud Peter (1916), The Triumphs of Sara (1920), Tony the Exceptional (1921), Next of Kin (1923), and so on. As the Times Literary Supplement suggested on 17 March 1905, W. E. Norris ‘inherits the tradition’ of Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) – though not, perhaps, Trollope’s wonderful irony.

In a 1906 work of literary criticism, The Mirror of the Century by Lord Walter Frewen (1861-1927), W. E. Norris occupies an entire chapter – ten further chapters discuss George Eliot, Jane Austen, The Brontës, W. M. Thackeray, Charles Dickens, Lord Lytton (Edward Robert Lytton Bulwer-Lytton), The Kingsleys (Charles, Henry and Charlotte), Lord Beaconsfield (Benjamin Disraeli), Anthony Trollope and Charles Reade.

Frewen writes enthusiastically about Norris as ‘the Gainsborough of English novelists’ and ‘as great a master of detail as Trollope’; his novels, Frewen writes, have ‘an almost Disraelian intensity’, are ‘always in full dress’ and ‘of remarkably even quality, and all of high merit’. In The Despotic Lady ‘we have some of the cleverest high-comedy situations of the century’ and, in The Countess Radnor, ‘finely chiselled phrases of which even George Eliot might have been proud’.

‘There can be no greater relief – yes, we must say it, “relief” – from reading George Eliot than a plunge into W. E. Norris. George Eliot had the force and grandeur of Milton, and an abundant sense of humour which Milton had not. Nevertheless, she is exhausting. To live on her high mental plane is a strain. After so much analysis and introspection one is athirst for a more composed presentment of things. Mr. Norris gives it us. Moreover, he comforts us by assuring us that virtue is not the monopoly of the poor; and that it is possible to be in possession of many of the good things of this life, and to enjoy them and yet to be a credit to humanity and a source of happiness to all around us. Best of all, we have a truly Gainsborough-like gallery of noble women. These dress beautifully, and hunt, and enjoy considerable incomes, and never say an unkind word of anybody. It is Mr. Norris’s glory that he has set his face against the cheap melodrama of evil, and has elected to tell us of good by preference.’

It seems strange, therefore, that by 1906 Norris was already something of a has-been. Frewen concludes:

‘Presumably somebody must read his writings; but I never met anybody who even knew his name except, twenty years ago, a lady who advised me to read No New Thing… Those who do not, miss a pleasure …’

I am now reading No New Thing (1883) on archive.org; a third of the way through volume one (there are three volumes), I find it a perfectly pleasant read – the ideal book to accompany afternoon tea in a summer garden. But, perhaps, that is the problem with W. E. Norris.

On 1 June 1916, the Times Literary Supplement reviewed Proud Peter:

‘From M. Norris we always look for a polished, well-written tale, breathing the peaceful air of a cultured country house… It is a pleasant, well-constructed story, full of pleasant people, whose pleasantness is only thrown into greater relief by the few unpleasant ones’.

The Torquay Times, and South Devon Advertiser declared on 3 October 1902:

‘There is no pleasanter writer than Mr. W. E. Norris, and it is perhaps from this very excess of pleasantness that we lose some consciousness of his excellent art, his clever method, and his smoothness of writing. He is an author who has invariably an interesting story to relate, which he does in a pleasantly cynical manner, but he is not one who reaches to any great height. His work is essentially gentlemanly, he can draw with the fidelity of a fully acquainted and close eyed observer that section of society he has chosen to exploit, but the photographic nature of his work militates against one’s regarding it in any way but that of a pleasantly cynical student’s appraisement of life.’

Similarly, The Illustrated London News remarked on 7 February 1903:

‘Quite recently Mr. W. E. Norris gave us a story that turned upon the supposed lightness of a wife’s character, and very pretty play he made, after his own manner, with the ensuing complications. In “Lord Leonard the Luckless” he has gone one worse, so to speak, and flounders amid squalid intrigue as hopelessly as only a habitually decorous writer can. … We wish him repentance, and a swift return to the society of the breezy people we like and expect to meet in this author’s pages’.

Finally, another Times Literary Supplement reviewer wrote of Barham of Beltana on 17 March 1905:

‘At this time of day he [Norris] is not ambitious; he is content to reproduce the surface of a certain section of contemporary English life, and he tells his simple story without any desire to discuss problems or suggest that everything is not precisely as it ought to be. He is the type of writer who regards marriage and the events that precede it as the legitimate end of a novel; and when he has satisfactorily disposed of the difficulties that are necessary to make a plot, the sound of marriage bells is the signal for a general handshaking, and we feel that we can all depart in a state of mild felicity… Mr. Norris does not take his art too seriously, and is a little amused by the whole business himself. His writing is always that of a gentleman quite at his ease, and whatever subject he treats he never loses his self-control or says a word more than he means… The present novel will not sadden; it will not excite; but it will provide an hour or two of healthy entertainment; and that, we imagine, is a result with which the author would declare himself content’.

It is too soon for me to draw conclusions about Norris from my own reading but in these early reviews words such as ‘pleasant’, ‘gentlemanly’, ‘pretty’, ‘decorous’, ‘breezy’, ‘simple’, ‘not ambitious’, ‘mild felicity’ and ‘healthy entertainment’ are clues, I suspect, to why we no longer read Norris. He wrote pleasant and highly readable stories – and what is the harm in that?

Anyway, back to my book and cup of tea…

Emma Laws, Director of Collections and Research