A General History of the Science and Practice of Music: a tragedy in two acts

Sir John Hawkins' greatest literary achievements were thwarted by bad timing and, according to some accounts, by the 'paltry malice, and base tricks' of his mean-spirited contemporaries.

Sir John Hawkins (1719-1789) was a friend of Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) – they were once frequent contributors to The Gentleman’s Magazine and Hawkins was a member of Johnson’s social and literary club, the Ivy Lane Club. Johnson appointed Hawkins as the executor of his will and upon Johnson’s death Hawkins began writing a biography – no doubt he believed that Johnson had entrusted to him his reputation as well as the distribution of his estate. But others among Johnson’s circle of friends were quick to disagree.

Hawkins’ life of Johnson was published in 1787 and immediately panned. Four years later, James Boswell (1740-1795) published his biography of Johnson and at the same time launched a virulent attack on Hawkins, claiming he had seen him in Johnson’s company, ‘I think but once, and I am sure not above twice.’ Boswell further claimed:

But what is still worse, there is throughout the whole of it a dark uncharitable cast, by which the most unfavourable construction is put upon almost every circumstance in the character and conduct of my illustrious friend …’

Hawkins’ nineteenth-century biographer came to his defence:

‘…he who undertakes to give to the world accounts of his contemporaries invariably runs the risk of incurring great animosity: and the more candidly and impartially he performs his task, the greater is his danger in this respect; for while the friends of the deceased consider that his virtues and amiable qualities are not sufficiently enlarged upon, those who disliked him, on the other hand, determine that his failings have been too much glossed over.’

He suggests, too, that Boswell was jealous of Hawkins’ friendship with Johnson and that there were many others besides who sought to profit from an association:

‘… there were, no doubt, others who had pleased their imaginations with the hope, that the slight acquaintance they might have with Johnson, would induce the writer of his life to hand them down to posterity as the friends of the great Lexicographer, and who, having travelled through the biography without attaining the ‘wished-for consummation’ of seeing their ‘names in print,’ were not inclined to view with very favorable eyes the labours of his historian.’

Whatever the truth of the matter, Hawkins’ biography of Johnson was certainly inferior and almost immediately forgotten while Boswell’s became a bestseller. Today, Boswell’s Life of Johnson is widely reputed to be one of the greatest biographies ever written.

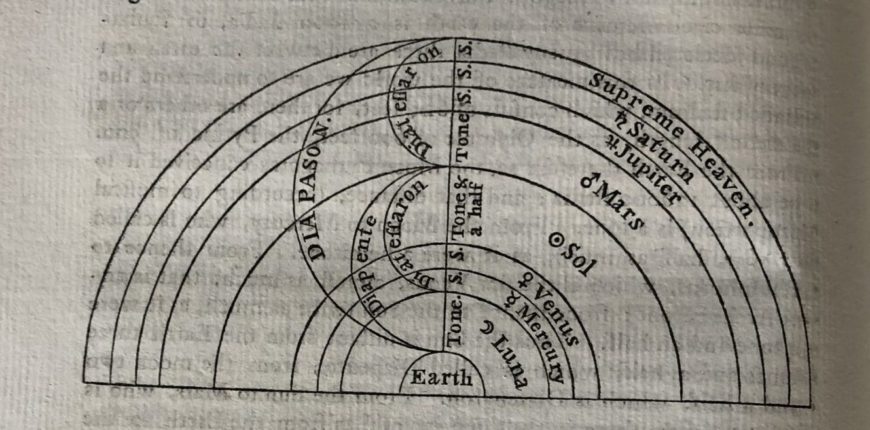

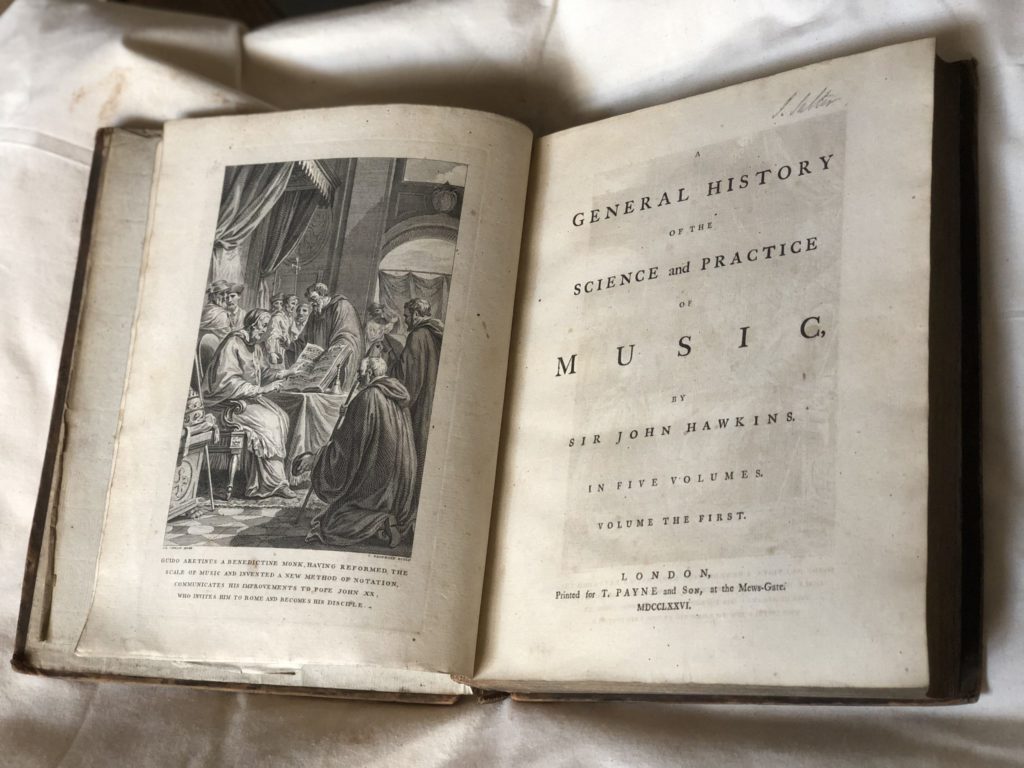

Unfortunately, Hawkins’ remarkable history of music suffered a similar fate. Sixteen years in the writing, Hawkins’ five-volume masterpiece appeared in 1776 but within weeks it was eclipsed by the publication of the first volume of a subsequent book of the same title – A General History of Music by Charles Burney (1726-1814), a professional musician:

‘The public did not even compare the respective merits of the works: they eagerly purchased the professor’s history, while that of the amateur was left unasked for, or sneered at, on the publisher’s counter.’

Burney went on to write and publish a further three volumes over the next thirteen years – arguably an easier task since he had Hawkins’ complete work to reference and, no doubt, to borrow from. Sadly, Hawkins’ work ‘did not even furnish a pair of carriage horses to its author’. Instead, booksellers, apparently, sold Hawkins’ book for wastepaper or disposed of copies in their cellars, ‘so that now hardly a copy can be procured undamaged by damp and mildew’.

Hawkins’ biographer concluded: ‘few persons have been, both during life and after death, so rancorously attacked as Sir John Hawkins’. History, however, has been somewhat kinder to Hawkins; his history of music is recognised as a valuable source of information. Since copies are rare, I am delighted the Institution’s Library preserves a complete first edition. In fact, Hawkins and Burney can finally share the same shelf – the amateur complementing the professional.

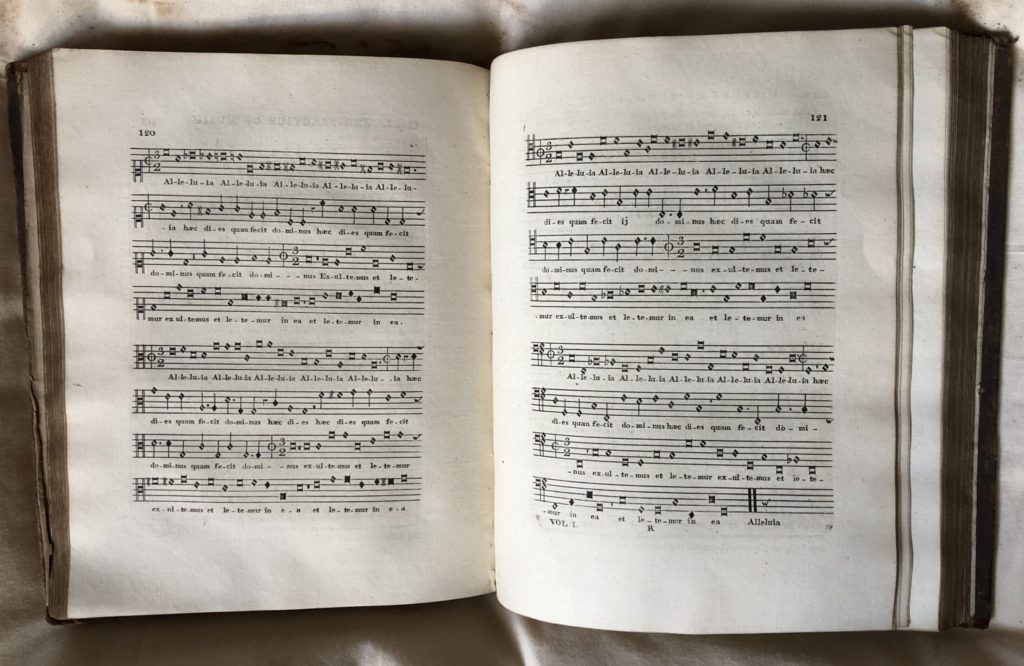

Hawkins’ history of music is a product of the Enlightenment and a testament to its prevailing spirit of enquiry. Unlike Burney, Hawkins had ‘no prototype of his great work. The design, as the execution, was entirely his own’. He considered music a science and approached his research diligently and with a scientist’s attention to detail:

‘…recourse has been had to the Bodleian library and the college libraries in both universities; to that in the music-school at Oxford; to the British Museum, and to the public libraries and repositories of records and public papers in London and Westminster; and, for the purpose of ascertaining facts by dates, to cemeteries and other places of sepulture …’

The result is a ‘delightful book … of the most curious and entertaining information upon a subject the most enchanting’ – truly, an amateur’s ‘labour of love’, and probably the better for it.

In 1875, the music publishers, Novello, Ewer & Co., sought to ‘rescue a worthy, honest name … and to reclaim his literary efforts’ by publishing a new edition of Hawkins’ history of music with a ‘Life of Sir John Hawkins, compiled from original sources’. The entire text is available online here.

Emma Laws – Director of Collections and Research