A ‘Cornish boy, in tin-mines bred’: the legend of John Opie (1761-1807)

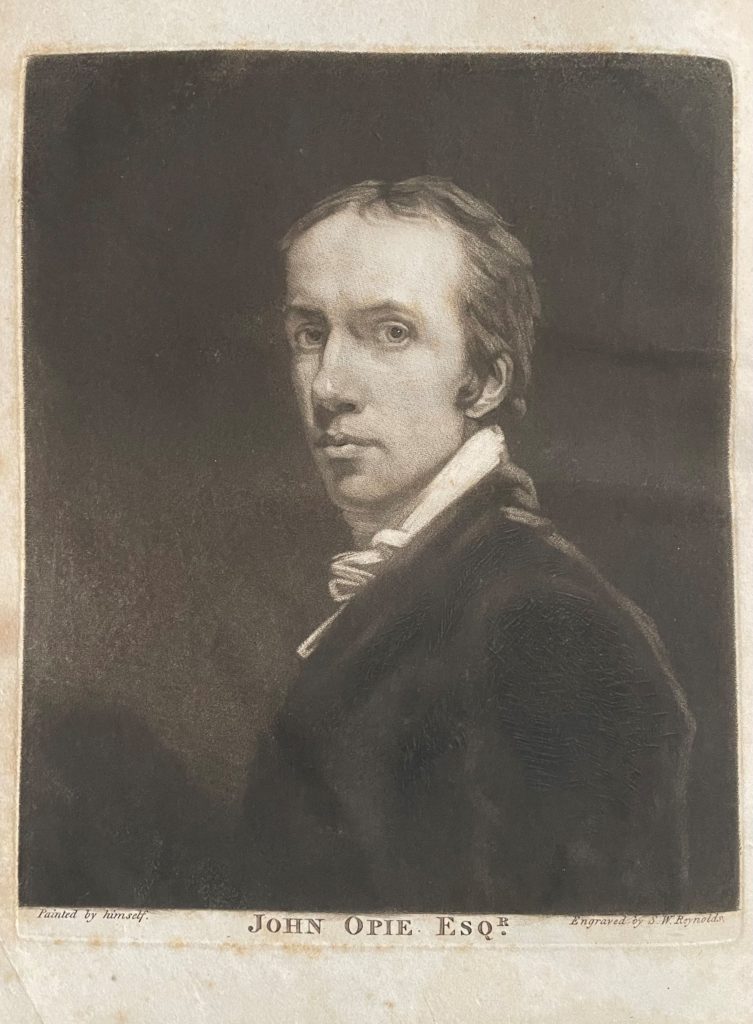

Born in Mithian, St Agnes, Cornwall, John Opie (1761-1807) overcame his humble birth to become a Royal Academician and one of the foremost portraitists and landscape artists of his day. He was introduced to the London art world as a self-taught Rousseauian 'noble savage', raised in a ‘remote and secluded part of the island’, who rose to fame ‘unassisted by partial patronage’. However, little of this was true.

Despite being educated at the local village school, John Opie certainly developed a flair for drawing and mathematics and even began teaching other children when he was still a child. His father, however, saw little value in his artistic abilities and insisted he be apprenticed to a local sawyer. Rather fortuitously, Dr John Wolcot (1738-1819), a local physician and satirist who published under the name of Peter Pindar, is said to have visited the sawmill one day in 1775 and observed John Opie’s natural artistic talent.

Wolcot immediately took Opie under his wing; he bought him out of his apprenticeship at the sawmill and invited him to live in his own home in Truro where he guided and mentored him for several years. Wolcot was well-connected and gained commissions for his protégé in Falmouth, Exeter and Plymouth. It was probably Wolcot who engineered the illusory title of Opie’s first exhibited painting at the Society of Artists in 1780: ‘Master Oppy, Penryn, A Boy’s Head, an instance of Genius, not having seen a picture’. Of course, nothing could have been further from the truth; by now, Opie had enjoyed five years under Wolcot’s patronage and four years’ experience as a portraitist. But Wolcot was creating a backstory for his protégé that would ensure him a popular reception in London the following year.

Wolcot immediately took Opie under his wing; he bought him out of his apprenticeship at the sawmill and invited him to live in his own home in Truro where he guided and mentored him for several years. Wolcot was well-connected and gained commissions for his protégé in Falmouth, Exeter and Plymouth. It was probably Wolcot who engineered the illusory title of Opie’s first exhibited painting at the Society of Artists in 1780: ‘Master Oppy, Penryn, A Boy’s Head, an instance of Genius, not having seen a picture’. Of course, nothing could have been further from the truth; by now, Opie had enjoyed five years under Wolcot’s patronage and four years’ experience as a portraitist. But Wolcot was creating a backstory for his protégé that would ensure him a popular reception in London the following year.

Wolcot and Opie moved to London in 1781. As Peter Pindar, Wolcot included a puff to Opie in his Lyric Odes to the Royal Academicians for 1782, introducing him in a sonnet addressed to the Exeter Cathedral organist, William Jackson, whose portrait Opie had painted. (Jackson had previously helped Wolcot’s career by setting some of his poems to music.)

Speak, Muse. Who formed that matchless head?

The Cornish boy, in tin-mines bred,

Whose native genius, like her diamonds, shone

In secret, till chance gave them to the sun.

Wolcot presented Opie to the London art world as a ‘Cornish wonder’ and curated his unkempt appearance and ‘habitual ruggedness’. Opie’s wife, Amelia Alderson, recalled:

When he first came to London … it was reported that he used to speak unpleasant truths, which the humour that they were delivered with could scarcely render palatable. But I have reason to think that these his recorded sayings were invented, and related by a friend who wished to make him an object of public attention, and fancied that, the more of a savage he was represented to be, the greater wonder he would appear as a painter…

Opie was a success: Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), President of the Royal Academy, compared him to the great Italian artist, Caravaggio, while others called him an ‘English Rembrandt’; even the King purchased a couple of his pictures. Opie went on to paint the leading men and women of his day, including Mary Wollstonecraft, Samuel Johnson, Edmund Burke, Henry Fuseli, Robert Southey, Thomas Girtin, Elizabeth Inchbald and Mary Shelley. In 1787 he was elected a member of the Royal Academy.

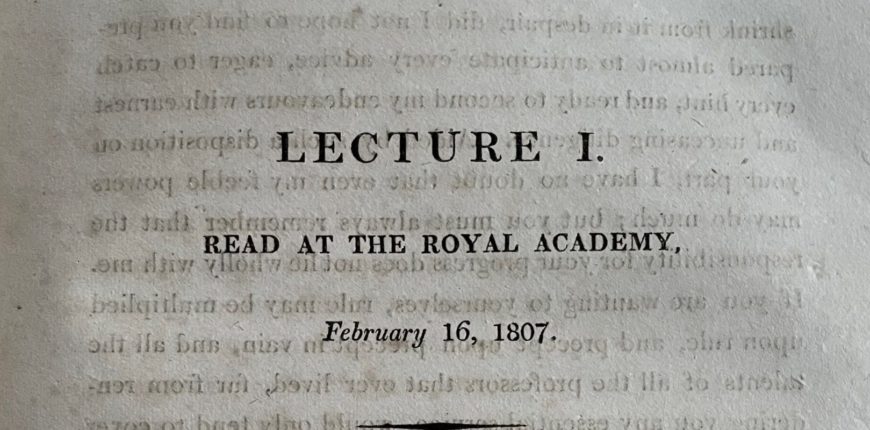

Opie delivered lectures to the Royal Institution and gave a series of four lectures to the Royal Academy in spring 1807:

he shone more as professor at the Academy, than as lecturer at the Institution, because he was more formed by nature and application to address the studious and philosophic, than the light and gay.

A month later, however, John Opie died of fever; he is buried in St Paul’s Cathedral next to Sir Joshua Reynolds.

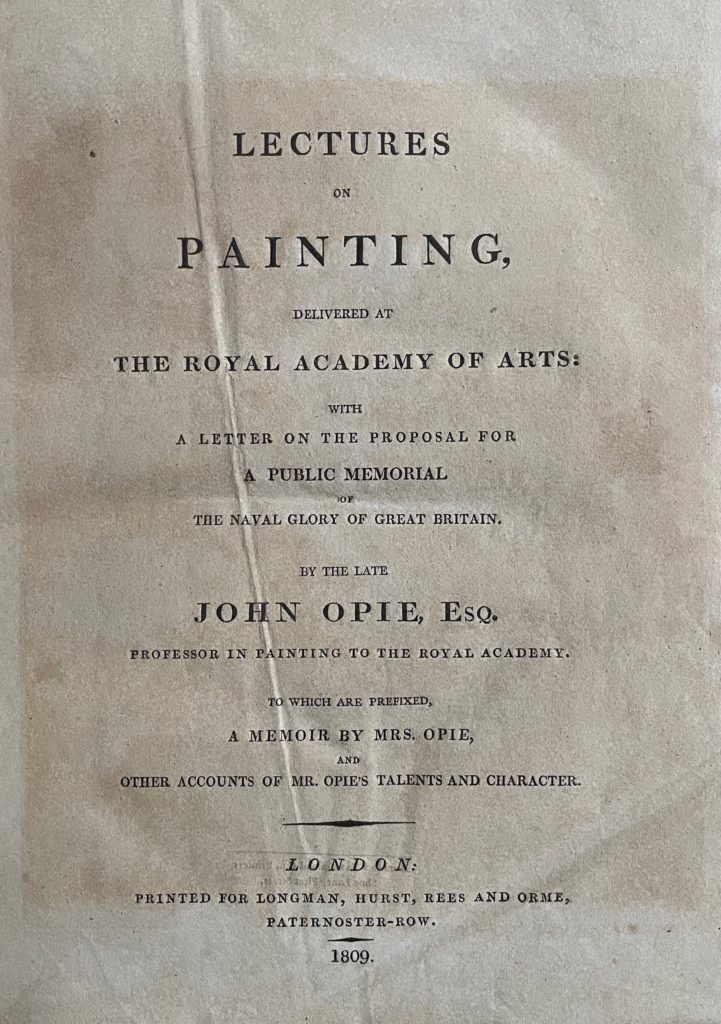

Opie’s Royal Academy lectures were published posthumously in 1809 as Lectures on painting, delivered at the Royal Academy of Arts … to which are prefixed, a memoir by Mrs. Opie, and other accounts of Mr. Opie’s talents and character. The copy pictured here is held in the Library at the Devon and Exeter Institution. These various accounts and tributes authenticated the legend of Opie as a self-taught man who rose to greatness unsupported.

The Cornish clergyman and poet, Richard Polwhele, described Opie as ‘a wild animal of St. Agnes, caught among the tin-works’. Opie’s contemporary, James Northcote (1746-1831), a Plymouth portraitist and landscape painter and fellow Royal Academician, wrote of his friend:

Born in a rank of life, in which the road to eminence is rendered infinitely difficult, unassisted by partial patronage, scorning with virtuous pride all slavery of dependence, he trusted alone for his reward to the force of his natural powers, and to well directed and unremitting study…

Similarly, a ‘Tribute to the Memory of Opie’ by Sir Martin Archer Shee (1769–1850) fails to mention anything of Wolcot’s starring role in Opie’s career:

No feeble follower of a style or school;

No slave of system in the chains of rule:

By his own strength his merits be amass’d

And liv’d, no dull dependent on the past:

His genius kindling from within was fir’d,

And first in nature’s rudest wild aspir’d.

Opie painted at least eight portraits of John Wolcot, one of which now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, London. Wolcot continued writing satires until his death in 1819.

Emma Laws, Director of Collections and Research

The full text of Opie’s lectures can be read here.