Women’s Travelogues: Elizabeth Caroline Johnstone Gray and Amelia Blandford Edwards

In the first of a special edition three-part Book of the Month, history MA student Isabel Moon explores the works of the 19th-century women who feature in our Voyages and Travels collection. She has been looking at these works as part of an ongoing project, which asks how we should use this material as a 21st-century audience. This piece explores what drew these female travel writers to the genre, and the topics which they chose to explore, and tries to bring context to both the good and the bad in their books. How might modern readers engage with works that reflect Victorian ideas about “otherness” and the wider world? And what is the best use of books like these today?

Elizabeth Caroline Johnstone Gray

Tour to the Sepulchres of Etruria, in 1839 (1843)

Elizabeth Caroline Johnstone Gray is most famous for her contribution to the study of the ancient civilisation of the Etruscans in Italy. With some calling her “the female pioneer of Etruscology in Britain,” she was the first to bring Etruria – its archaeology and antiques – to the attention of the British public. In this book, she describes her journey around Etruria, visiting the cities, sites, and most importantly, the sepulchres, along her journey.

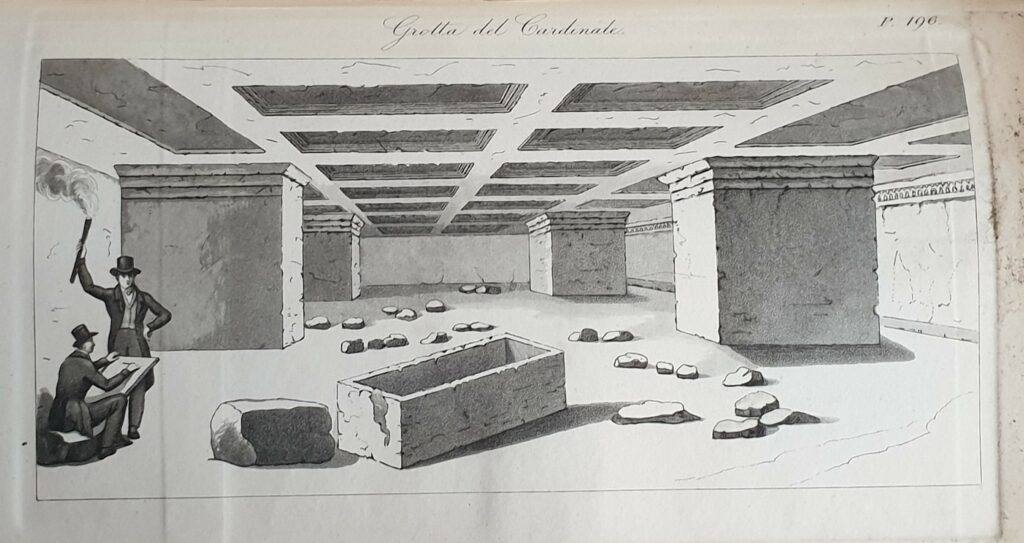

Our modern word “tourism” comes from the word “tour” as we see it used in the title of Gray’s book. The tourism industry expanded massively during the 19th century, as did the accompanying creation of travel guides such as this one. As a result, the reader gets an interesting mix of archaeology, adventure, and sightseeing that takes you through Gray’s journey as she discovers more about the country and its history. She takes a keen interest in the history and antiques of Etruria, visiting a lecture by an Archaeology Society and describing in great detail the history and study of vases and other antiques. On multiple occasions, she enters the tombs, describes their contents, and goes into details about the practices and history of tomb excavators. We see a carefree approach to historical antiquities which we today might consider unprofessional, even unethical, but also a relatable curiosity and enthusiasm, and Gray’s writing invites the reader to share in her disappointment and sadness when, upon entering one tomb, she finds that it has already been opened and sealed back up poorly.

Amateur archaeology and the collection of artifacts from around the world was prolific in the 19th century. It also formed part of the Devon and Exeter Institution’s history and played a vital part in establishing their collections. Prior to the donation of many of its artifacts to the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, the DEI housed a variety of artefacts collected by amateur antiquarians, the largest being Mr Frank H Lees’ moth collection and Lieutenant Francis Godolphin Bond’s Polynesia collection. Gray’s book interestingly gives us a first-person perspective on the Victorian antiquarians who played this important part in establishing British museum collections.

As a woman writing in a genre heavily associated with educated upper-class young men, for whom the ‘Grand Tour’ to Europe and beyond remained a rite of passage throughout the 19th century, Gray had to combat assumptions about her work and her abilities. She begins apologetically, explaining the academic limitations of her work, which she deems better suited for the “ignorant and pleasure-loving traveller, and not for the learned and antiquarian”. One review by explorer George Dennis highlights the prejudices that women travel writers faced. He writes that “the female mind is warm, imaginative, indisposed to doubt, eager to conclude” and that any “deep or Earnest” investigation into “matters concerned w[ith] the social instit[utio]n of a gentle nation” was “not properly within the female province”. Despite comments like this, Gray’s book went on to be a notable success.

Amelia Blandford Edwards

A Thousand Miles up the Nile (1877)

Amelia Blandford Edwards was an author, journalist, and Egyptologist born in London in 1831. In 1873, Edwards and a close friend of hers, Lucy Renshaw, set off for Egypt on a trip widely considered to have changed the course of her life. She would go on to dedicate herself to Egyptology, founding the Egypt Exploration Fund in 1882.

A Thousand Miles up the Nile is an engaging work, described by Eamonn Gearon as “one of the most remarkable accounts of Egypt in print”. The book is full of immersive descriptions of the sights surrounding Edwards as she travelled, which are representative of a larger movement in 19th-century travel writing from scientific to more picturesque and romantic language. Her use of colour and imagery brings the beauty of the landscape to life, and her descriptions of the environment make the reader feel like they are right there alongside her. At the time of this book’s publication, Egypt was a popular topic in Britain as both England and France raced to discover the source of the Nile. Edwards’ dark and tense descriptions of mummies and tombs fit well with the growing “Egyptomania” and the rise of Egypt-focused gothic and horror literature in the late 19th- and early 20th-centuries.

“He offered [a papyrus] first, with a mummy, for £100. Finding, however, that we would neither buy his papyrus unseen nor his mummy at any price, he haggled and hesitated for a day or two, evidently trying to play us off against some rival or rivals unknown, and finally disappeared[…] [These rivals], bought both mummy and papyrus at an enormous price; and then, unable to endure the perfume of their ancient Egyptian, drowned the dear departed at the end of a week.”

At the time of her visit, the trade in Egyptian artefacts was prolific, and this is something that, throughout the book, Edwards became increasingly concerned about. Her description of this trade is full of menacing imagery that conveys Edwards’ perception of an illicit underworld. She describes meeting a “mummy-snatcher” in Thebes who, from the moment she and her companion expressed an interest in a papyrus, “regarded [them] as his lawful prey.” Later, Edwards describes viewing a mummy in a “a dark and dusty vault”, where it lay ” on an old mat at [her] feet.”

Despite her qualms, evidence suggests that she at some point owned mummified body parts. In an autobiography she wrote for The Arena in 1891 she describes having “three mummified hands” “in the library,” “two arms” “in a draw in my dressing room,” and “grimmest of all, I have the heads of two ancient Egyptians in a wardrobe in my bedroom, who, perhaps, talk to each other in the watches of the night, when I am sound asleep.” Edwards was considered one of the more legitimate collectors of the time by her contemporaries. Her collection eventually went to University College London to establish an Egyptian Museum the year she died, now called the Petrie Museum.

“Perhaps I ought to say something in answer to the repeated inquiries of those who looked for the publication of this volume a year ago[…] To write rapidly about Egypt is impossible. The subject grows with the book, and with the knowledge one acquires by the way.”

Many scholars have interpreted Edwards’s apology for the book’s lateness and her comment about having spent the last two years studying the ever-growing field of Egyptology as a sign of her academic intentions for this book. But Edwards also uses romantic language throughout to depict Egypt in exciting detail for casual readers. As John Marx describes, she takes full advantage of the conventions of the travelogue genre to change England’s relationship with the cultural legacy of Egypt. Edwards uses her vivid descriptions to contrast with the bustling tourism industry in Egypt. She moves focus away from souvenirs and spending money and towards the sights and ancient splendour that Edwards’ herself was so passionate about. Edwards published this book at a turning point between the lower levels of interest in Egyptology in the years before and the heightened “Egyptomania” of the following decades. Most historians agree that Edwards’ mix of academic and creative content significantly contributed to this change.