Well-met by moonlight: Illuminating the astronomical treasures of the DEI collection

In the Age of Enlightenment, in which our own Institution was founded, various individuals turned to the skies. As a professional science, Astronomy was still relatively young in the early nineteenth century, and tended to be pursued by amateurs with the financial means to do so, as was illustrated by the demographic of the fourteen men who met in London to found the Royal Astronomical Society in 1820. Nonetheless, in printed volumes, published lectures, and paraphernalia from determined enthusiasts, there is evidence of an infectious spirit of curiosity and learning, a story which is corroborated by various items from the Devon and Exeter Institution’s Special Collections.

In the 1700s, in a desire to inform and educate, John Harris delivered lectures on Astronomy at the Marine Coffee House in Birchin Lane, London. Offered free to the public and established by Charles Cox. M.P, Harris’ instructions pertaining to the description and use of the globes, and the Orrery, were converted into published form in 1704. Our 1732 edition, complete with illustrative diagrams and fold-out maps of the solar system, suggests his work remained of interest for a considerable time. New editions of Harris’ volumes were released for several years throughout the following century.

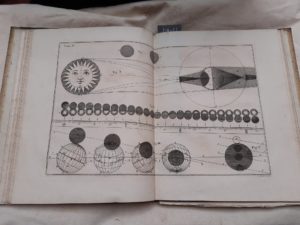

David Brewster, Astronomy, Plates Illustrative of Ferguson’s Astronomy, Edinburgh: Ballantyne, 1811.

In 1811, the renowned Edinburgh Encyclopaedeia editor David Brewster set about an edited volume dedicated to the work of the self-taught, itinerant lecturer James Ferguson. As a young man in Rothiemay, Scotland, Ferguson had taught himself to read, and later had only three months of formal education at Keith Grammar School, at the age of seven. After setting himself up as a successful instrument maker and miniature portrait painter in Edinburgh, Ferguson moved to Inverness and published his first work on Astronomy. He later made his home in England, where he travelled to give popular lectures on aspects of his work, supported by his own diagrams and models. In later life, he was supported by a Government pension due to his contribution to the advancement of science and scientific education. This volume, Astronomy, with Plates Illustrative of Ferguson’s Astronomy, by David Brewster, a esteemed writer and scientist in his own right, attests the legacy of Ferguson’s work for years after his death.

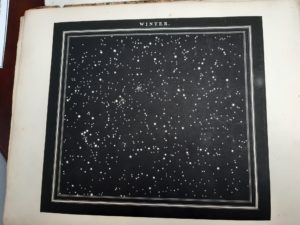

It seemed a similar spirit inspired the enthusiastic educator James Middleton to publish his Celestial Atlas in 1842, for the benefit of his students. Containing five sets of charts relating to the stars visible from Great Britain, Middleton’s work, complete with hand-drawn figures illustrative of the constellations, is both instructive and quaint, a beautiful testament to a time in which Astronomy was still emerging from its links to the more fanciful practice of Astrology. As he reflected on his work, Middleton asserted that if his reader pursued “the plan thus recommended… a knowledge of the heavens […would be…] much sooner acquired than a knowledge of the earth.” With careful diagrams and a straightforward introduction, Middleton’s volume also evidences a considered combination of modern and traditional printing techniques.

James Middleton, A celestial atlas, containing maps of all the constellations visible in Great Britain, London : Whittaker and Co.; Norwich, Jarrold and Sons, 1842.

Lunar photograph by Lewis Morris Rutherfurd, Richard A. Proctor, The Moon: her motions, aspect, scenery, and physical condition, Longmans: Green, 1873.

As the population became more literate, and with increased access to magazines and periodicals that sought to bring scientific knowledge to the masses, the democratization of scientific knowledge became more widely achievable. It was in such an environment that Richard A. Proctor, the lawyer-turned popular scientist writer, turned to the pioneering photographer Lewis Morris Rutherfurd to illustrate his volume about the moon in 1873. The plates beside the frontispiece of Proctor’s lunar text are photographs taken through a telescope by Rutherford from his studio in the 1870s, whilst diagrams and drawings illustrating various views of the moon are dispersed throughout. Proctor’s oeuvre, including his intended twelve-part text on Old and New Astronomy (later completed by Arthur Cowper Ranyard), owe their success to a contemporary thirst for knowledge that was created and encouraged by the advancement of the periodical press. In such an environment, inspired by the knowledge he had gained from the English Mechanic, the irrepressible stationmaster of Silverton Railway Station, Mr. Roger Langdon, began to make his own telescopes following his relentless day’s work. In 1864, he created a remarkable model of the moon’s visible hemisphere, which was subsequently donated to the Devon & Exeter Institution.

Overall, this display illuminates a phase in which Astronomy was emerging as a serious science, and a desire on the part of determined individuals to advance and build on the work of their predecessors. It is this early spirit of enthusiasm and collaboration which we hope to carry forward. To see the treasures discussed here and other volumes, do come and visit our display in the Outer Library- it’s certainly illuminating!