The Great Exhibition – 170 years on

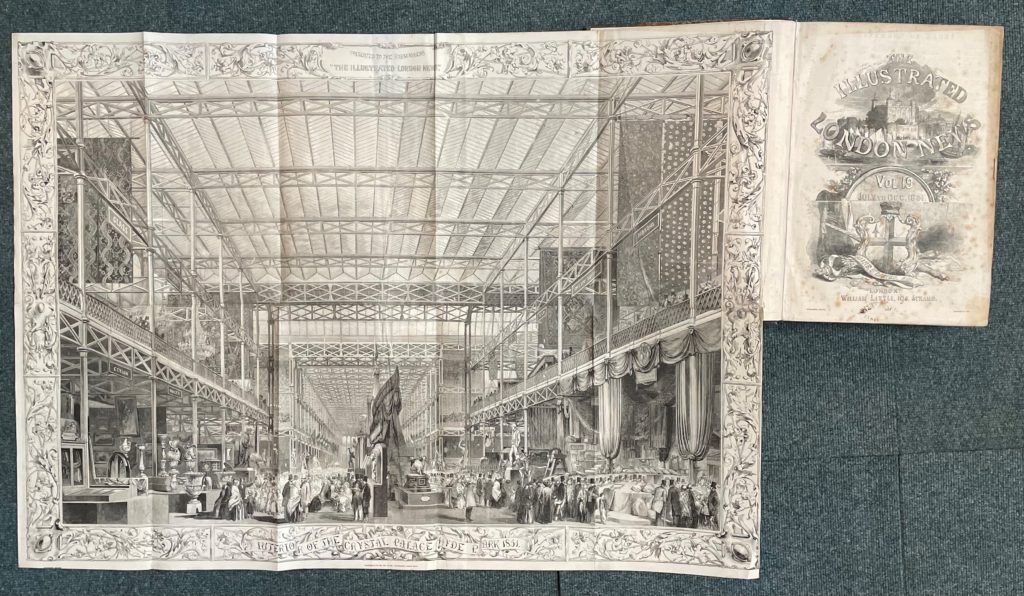

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations opened in Hyde Park, London, on 1st May 1851. It was spearheaded by Prince Albert and members of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (later the Royal Society of Arts), including Sir Henry Cole. The Crystal Palace - an incredible cast iron and glass structure, measuring 1848 feet long and 454 feet wide – was constructed in just nine months. The Great Exhibition was to be a ‘wonder of the world’ – a celebration of international industrial design and technology with exhibits from all corners of the earth. But, principally, it was to be a grandstand for Britain and for British manufacturing.

A Royal Commission formed in 1850 to plan and organise the Exhibition and to disseminate information across the country. Henry Cole (1808-1882), John Scott Russell (1808–1882) and Francis Fuller (1807–1887) were initially tasked with promoting the Exhibition and drumming up financial support. Here in Exeter, as in other towns and cities across the country, a local Exhibition Club was established. Committee meetings were held at the Guildhall on the High Street, chaired by Robert Dymond, (1824-1888), who subsequently became Honorary Secretary of the Devon and Exeter Institution, a committee member of the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, and author for five years of the Report of the Committee on Works of Art in Devonshire. Charles Brutton (1791-1854), a former mayor of the city, was the Club’s Honourable Secretary. The committee received and disseminated circulars from the Royal Commission and assembled exhibits to celebrate the region’s industry and manufacturing.

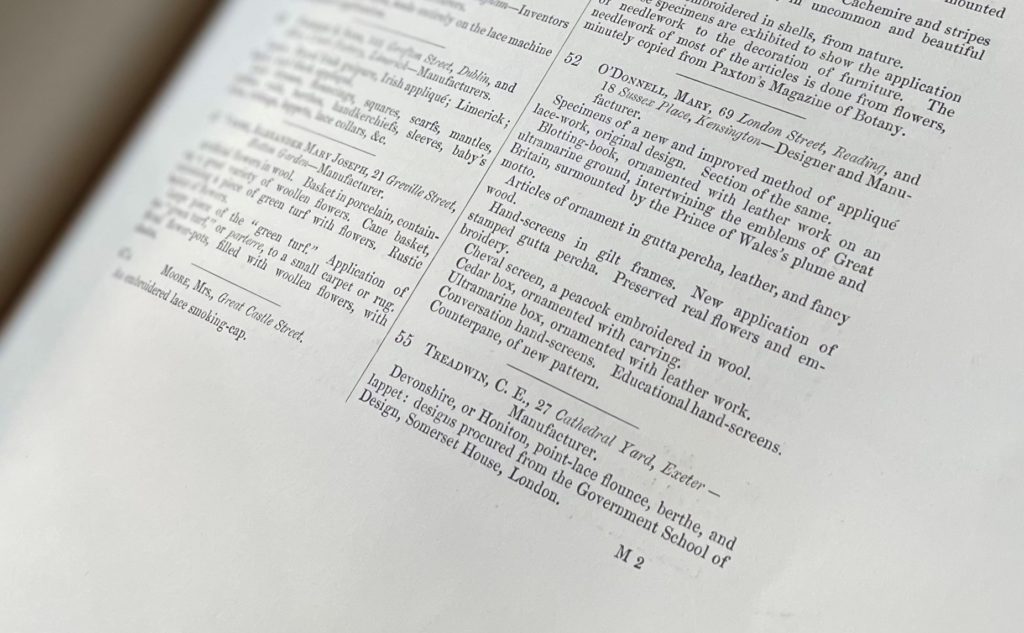

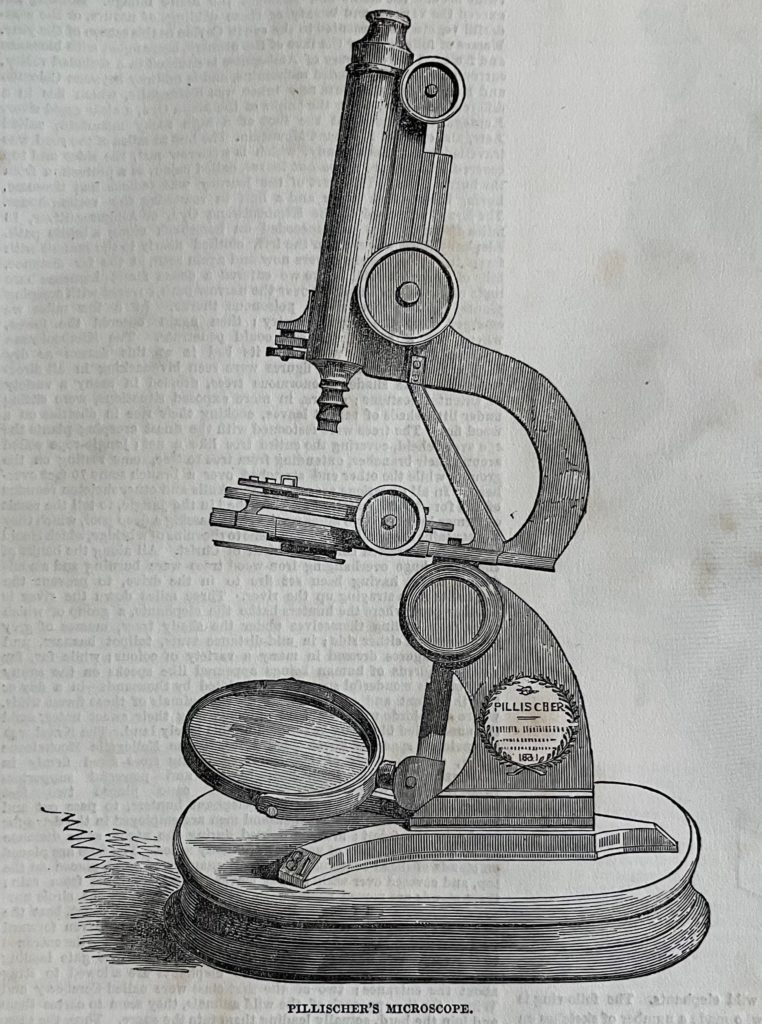

The Devon and Exeter Institution has a wealth of material relating to the Great Exhibition. Local newspapers offer information about the region’s short-listed exhibitors, including: Charlotte E. Treadwin (27 Cathedral Yard), articles of Honiton point lace; John Risdon (194 High Street), a fancy silk and velvet quilt; John Thomas Tucker, a patent for a universal brooch protector; William Clifford, a model of the West Front of the Cathedral made of ‘the pith of the common rush’; Henry Ellis & Son, a timepiece and brooches; Joseph Wippell (High Street), an octagonal alms-basin; James Williams (40 Exeter Street), a linen basket; Elizabeth Stirling (Mrs. Pinn’s, St. Thomas), an ivory statuette; John Bowring, the owner of a model bed-stead, and Thomas Kerslake, a boiler for heating churches, mansions and manufactories. Charles Brutton was the owner of a ‘most extraordinary and magnificent clock’ designed and constructed by Jacob Lovelace – a ‘wonderful production of ingenuity, perseverance, and mechanical skill’ (Exeter Flying Post, Thursday 23 January 1851).

The Devon and Exeter Institution has a wealth of material relating to the Great Exhibition. Local newspapers offer information about the region’s short-listed exhibitors, including: Charlotte E. Treadwin (27 Cathedral Yard), articles of Honiton point lace; John Risdon (194 High Street), a fancy silk and velvet quilt; John Thomas Tucker, a patent for a universal brooch protector; William Clifford, a model of the West Front of the Cathedral made of ‘the pith of the common rush’; Henry Ellis & Son, a timepiece and brooches; Joseph Wippell (High Street), an octagonal alms-basin; James Williams (40 Exeter Street), a linen basket; Elizabeth Stirling (Mrs. Pinn’s, St. Thomas), an ivory statuette; John Bowring, the owner of a model bed-stead, and Thomas Kerslake, a boiler for heating churches, mansions and manufactories. Charles Brutton was the owner of a ‘most extraordinary and magnificent clock’ designed and constructed by Jacob Lovelace – a ‘wonderful production of ingenuity, perseverance, and mechanical skill’ (Exeter Flying Post, Thursday 23 January 1851).

Exhibiting at an international exhibition was a once in a lifetime opportunity for local manufacturers seeking to expand their businesses and perhaps even attract royal patronage:

‘Mr Woodley from the celebrated marble works at Mary Church, announced that he has a large table composed of the choicest Devonshire marbles, in a forward state of preparation, and this work was spoken of as likely to attract very great attention, from the beauty of the marbles, which Messrs. Woodley have done much to introduce, but the renown of which is destined to travel still more widely, it is hoped, through the medium of this great exhibition…’ (Western Times, 1 February 1851)

John Woodley’s marble works were exhibited in Class 27 – Manufactures in Mineral Substances, for Building or Decorations – on the north side of the Western Main Avenue.

The Western Times reported on the meetings of the Exeter Exhibition Club which, by all accounts, were ‘hearty’ affairs and well-attended. Various articles and reports offer some idea of the content of the Royal Commission’s circulars: exhibitors were asked to state their requirements for the display of their items, for example, whether they wanted a cotton or velvet covering. Indeed, ‘doubt was created as to whether parties would not be required to erect their own counter’ within the Crystal Palace. Evidently, local committees were also tasked with categorising their objects into one of the thirty exhibition classes:

The Western Times reported on the meetings of the Exeter Exhibition Club which, by all accounts, were ‘hearty’ affairs and well-attended. Various articles and reports offer some idea of the content of the Royal Commission’s circulars: exhibitors were asked to state their requirements for the display of their items, for example, whether they wanted a cotton or velvet covering. Indeed, ‘doubt was created as to whether parties would not be required to erect their own counter’ within the Crystal Palace. Evidently, local committees were also tasked with categorising their objects into one of the thirty exhibition classes:

‘Mr. Moses Dalton the ingenious lapidary, has, as is well-known, a beautiful table of native pebbles; the worthy exhibitor was doubtful as to the class in which his work should go, whither as Fine Art of Manufacture, the wording of the circular having left it doubtful to some, whether this mosaic table of stone should be entered under the head of Fine Art or Manufacture’. (Western Times, 1 February 1851).

Information on the exhibits had to reach London in time to publish the enormous catalogue. The Exhibition organisers printed thousands of application forms – ‘to the Catalogue what the manuscript of an author is to his proposed work’ – and circulated them, with instructions, to local committees. The final catalogue contained ‘the composition of some fifteen thousand authors; most of them authors for the first time, who have had their excrescences pruned, and their diction occasionally mended’. (‘The Catalogue’s Account of Itself’, extracted from Dicken’s Household Words, 23 August 1851, and reprinted in the Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue.)

Across the country, local Members of Parliament and businessmen sponsored fundraising initiatives; when William Pope, ‘working hatter of the Bonhay’, was unable to convey his ‘ingenious furnace for consuming smoke’ from Exeter to London, the ‘Hon. Secretary took the invention under his special patronage and kindly undertook to pay the expenses’. Brutton was true to his word; Pope’s ‘furnace for consuming smoke, with apparatus for producing naphtha, if required’ was exhibited in Class 22 – General Hardware, including Locks and Grates – situated on the south side of the Main Avenue.

The Great Exhibition generated numerous local exhibitions in the run up to the official opening of the Crystal Palace in May. Lack of time put paid to the Exeter Exhibition Club’s idea for a local charity exhibition but, ‘in any case, it would perhaps be hardly fair towards the great exhibition itself, for the strong muster of talent and ingenuity with which Exeter is prepared to astonish the modern Babylon, might damp the ardour of some of the exhibitors, and deter many of them from entering the lists against so much talent and ingenuity’. (Western Times, 1 February 1851).

Between 1 May and 15 October 1851, about 6 million people (a third of the population of Britain) visited the Great Exhibition – an average daily attendance of 42, 831. Famous visitors included Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, Charles Dickens, Lewis Carroll, George Eliot, Alfred Tennyson and William Makepeace Thackeray. Charlotte Bronte visited more than once: ‘It is a wonderful place – vast, strange, new and impossible to describe. Its grandeur does not consist in one thing, but in the unique assemblage of all things… It seems as if only magic could have gathered this mass of wealth from all the ends of the earth …’ (Letter to the Reverend Patrick Brontë, 7 June 1851, published in The Brontës: life and letters (1908), edited by Clement Shorter.)

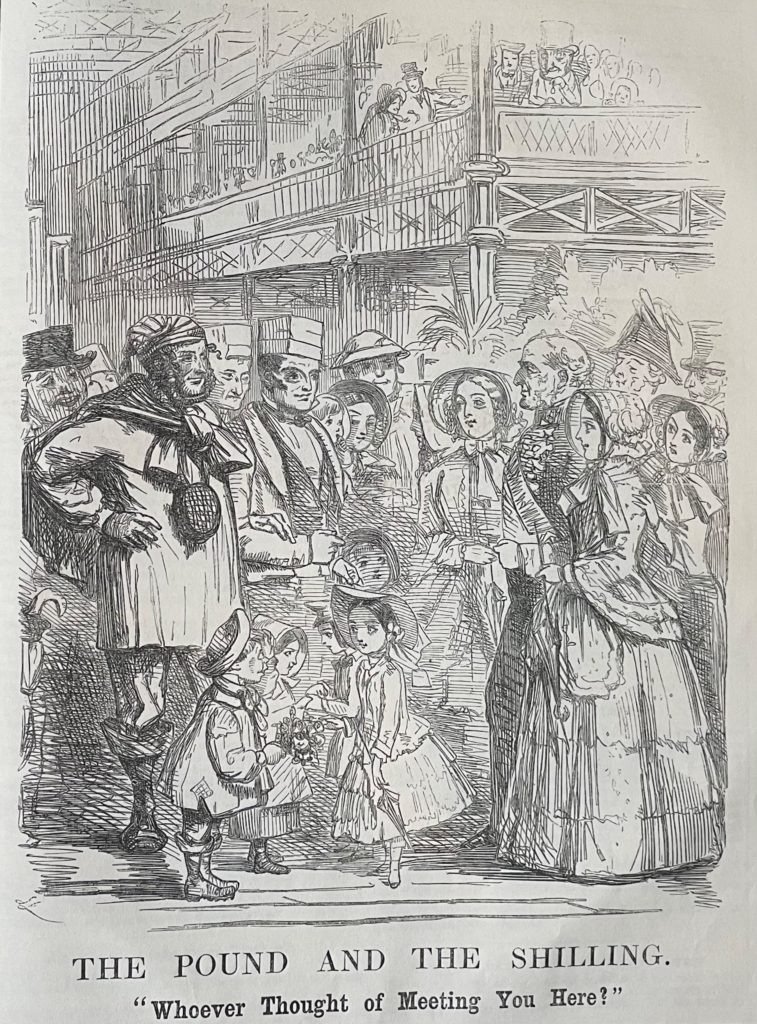

Local Exhibition Clubs, Mechanics Institutes, businesses, schools and churches fundraised so that everyone, rich and poor, could travel on the new train network to visit the Exhibition. The Exeter Flying Post (8 May 1851) remarked at the extraordinary convergence of the social classes: ‘Never before was so vast a multitude collected together within the memory of man’. (Exeter Flying Post, 8 May 1851). Punch cartoons were rather more satirical:

Advertisements for tickets, transport and lodgings (including affordable options for the working classes) appeared in local newspapers in early 1851. Admission prices varied. Tickets on the first two days cost £1 a day and the wealthy purchased season tickets at 3 guineas. Subsequent tickets cost 5s a day until 22 May, and thereafter 2s 6p on Fridays and 5s on Saturdays. The 1s ticket was popular among the working classes and railway companies offered discounted tickets and special rates to parties travelling from remote parts of the country. Punch mocked provincial visitors to the Exhibition in satirical sketches, poems and ballads:

The Country Clergyman to his Flock – a ballad of the Exhibition

Come, put on the best gown, and the cleanest smock frock,

And we’ll make an excursion, both Parson and Flock;

A day of your labour each master will spare,

And we’ll go up together to see the World’s Fair-

Lads and lasses,

Labouring classes,

You, my good folks, its enjoyment shall share.One-and-sixpence apiece will be all you’ve to pay,

Your wealthier neighbours the rest will defray;

You’ve saved up the money I’m happy to hear,

By giving up smoking, and guzzle, and beer.

All so steady;

You’ve the “ready,”

Stored for the Show of this wonderful year…’

Ballad for Old Fashioned Farmers on the Great Exhibition

You may zay what you like to about the World’s Fair,

But I’ve no inclination nor wish to goo there.

Your Palace of Crystial I don’t care to zee;

What good until the Varmer is it like for to be?I hears a vast deal, and I s’pose I shall moor,

About that famous dimond [sic] the gurt Koh-i-Noor,

That’s worth nigh a million, as folks do relate;

But what’s that with wheat down below thirty-eight?

Thomas Mayhew (1812-1887), co-founder of Punch, wrote a satirical novel about a fictional family from Buttermere in Cumbria, ‘who came up to London to “enjoy themselves,” and to see the Great Exhibition. Copies of the book, illustrated by George Cruikshank (1792-1878) and published by David Bogue in the year of the Exhibition, are extremely rare but the full text can be read online. Mayhew pokes fun at the rural working-classes as news of the opening of the Great Exhibition penetrates the provinces:

Thomas Mayhew (1812-1887), co-founder of Punch, wrote a satirical novel about a fictional family from Buttermere in Cumbria, ‘who came up to London to “enjoy themselves,” and to see the Great Exhibition. Copies of the book, illustrated by George Cruikshank (1792-1878) and published by David Bogue in the year of the Exhibition, are extremely rare but the full text can be read online. Mayhew pokes fun at the rural working-classes as news of the opening of the Great Exhibition penetrates the provinces:

‘Buttermere was one universal scene of excitement from Woodhouse to Gatesgarth. Mrs. Nelson was making a double allowance of her excellent oat-cakes; Mrs. Clark, of the Fish Inn, was packing up a jar of sugared butter, among other creature comforts for the occasion. John Cowman was brushing up his top shirt; Dan Fleming was greasing his calkered boots; John Lancaster was wondering whether his hat were good enough for the great show; all the old dames were busy ironing their deep filled caps, and airing their hoods; all the young lasses were stitching at all their dresses, while some of the more nervous villagers, who had never yet trusted themselves to a railway, were secretly making their wills – preparatory to their grand starting for the metropolis’.

A series of misadventures ensues, many of which would have been all too familiar to people travelling to the Exhibition, and Mr. Sandboy finally arrives at the ‘bothering Crystal Palace’ only to find it closed.

The Exeter Exhibition Club arranged several excursions in July and August and lengthy reports in local newspapers conjured the spectacular experience of the Crystal Palace in the imaginations of those who, for whatever reasons, could not attend. The first excursion departed the train station in Exeter on 5 July 1851 with nearly 600 Exhibition Club members on board (other members joined at Cullompton and Tiverton Road). For many, it would be the first and last journey anywhere by train, and an experience ‘the like of which none of the excursionists had ever seen before, and but few probably will ever live to witness again’.

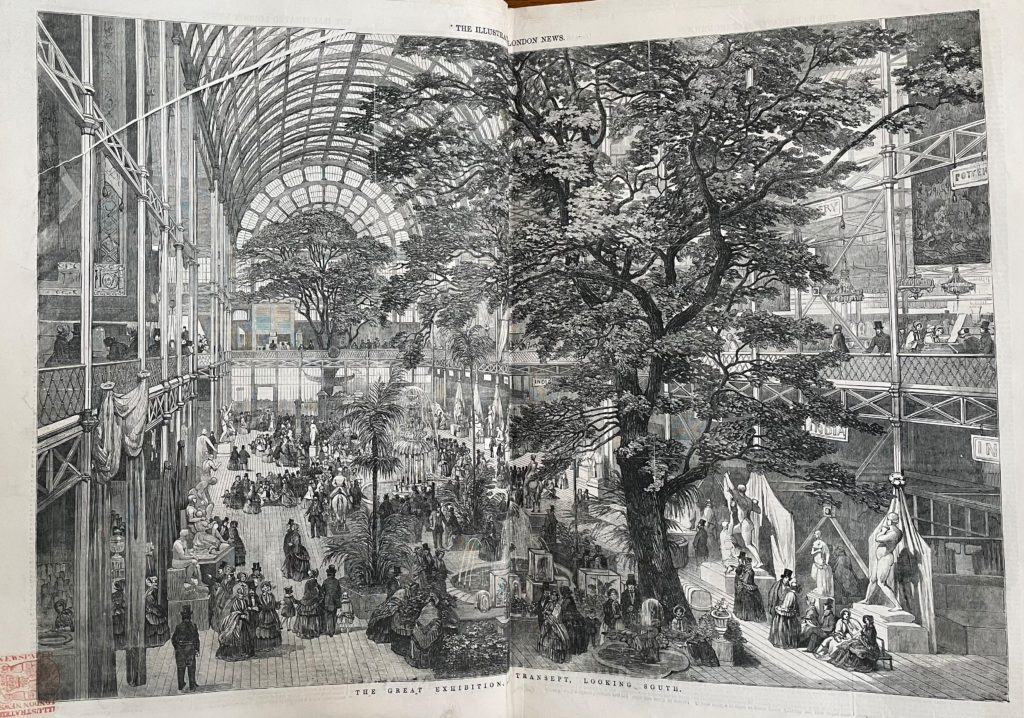

‘The first feeling of the visitor, we should say, is one of bewilderment – he looks before him, as far as the eye can reach he observes statuary, trophies, banners, beautiful tapestry, gorgeous carpets, wonderful gold, silver, and other metallic piles, candelabra, ornaments of every variety – the long and interminable vistas of pillars, delicately tinted with blue and white – the magnificent colors waving from the galleries. Overhead, the light of day pouring in a curtained stream from the transparent crystal roof, on each side the rush of thousands of spectators all astonished at the stupendous scene – and the hum of voices like the sound of many waters meets his ears. As he walks on, the sparkling drops of water falling like brilliant diamonds from the glistening fountain in the transept …

Perhaps a stranger may form some idea of the extent at least of the building, by comparing it with other localities with which he is familiar. Imagine then a building occupying twenty acres of ground, so long that it would reach from about St. Sidwell’s Church up to St. Ann’s Chapel, so much broader than the Exeter Cathedral is long, taking the latter from its extreme ends, the great door of the west, to the end of the Virgin Mary’s Chapel, on the east, and so high that the whole cathedral, if the towers were slightly lowered, could stand under the transept of the Exhibition, and the reader would have some notion of the extent of this wonderful building … Supposing the roof of the Cathedral to be of glass, the row of massive columns removed, and iron ones substituted about the fiftieth part of their diameter, and these columns extended six deep on each side, and it would bear some resemblance to the Palace.’ (Western Times, Saturday 12 July 1851)

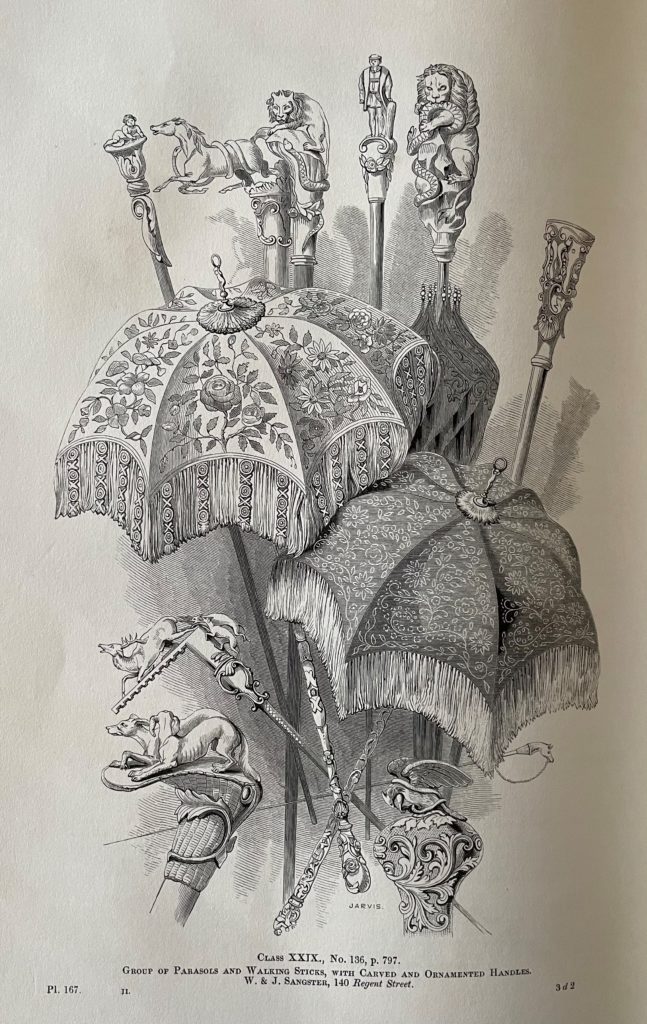

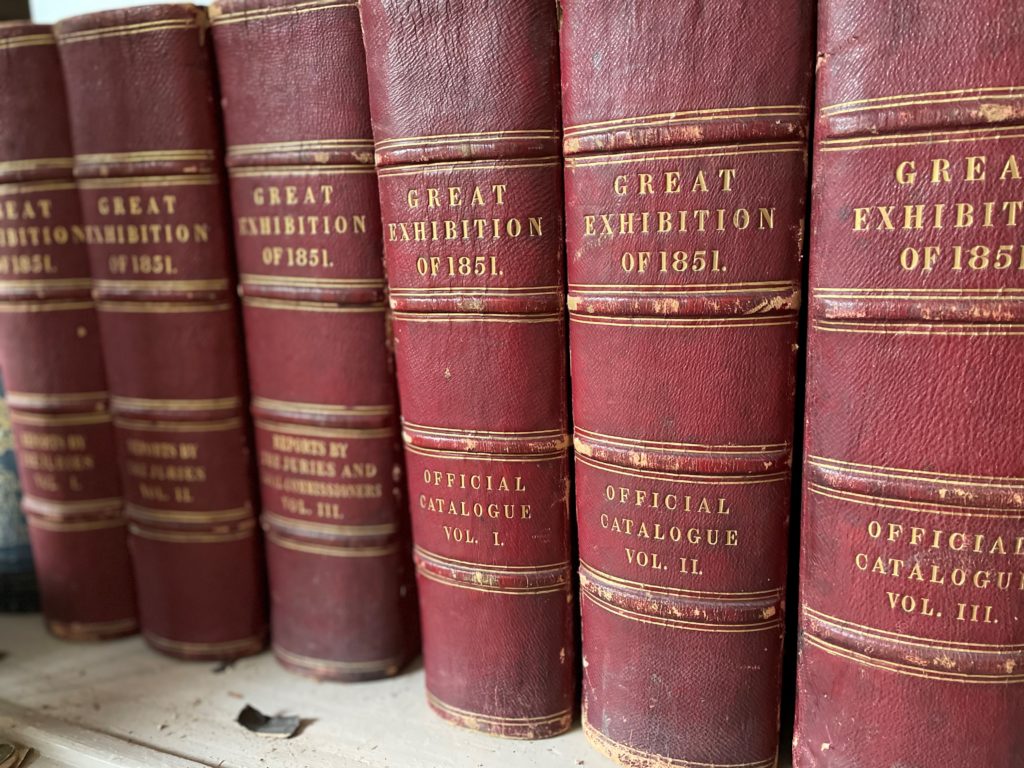

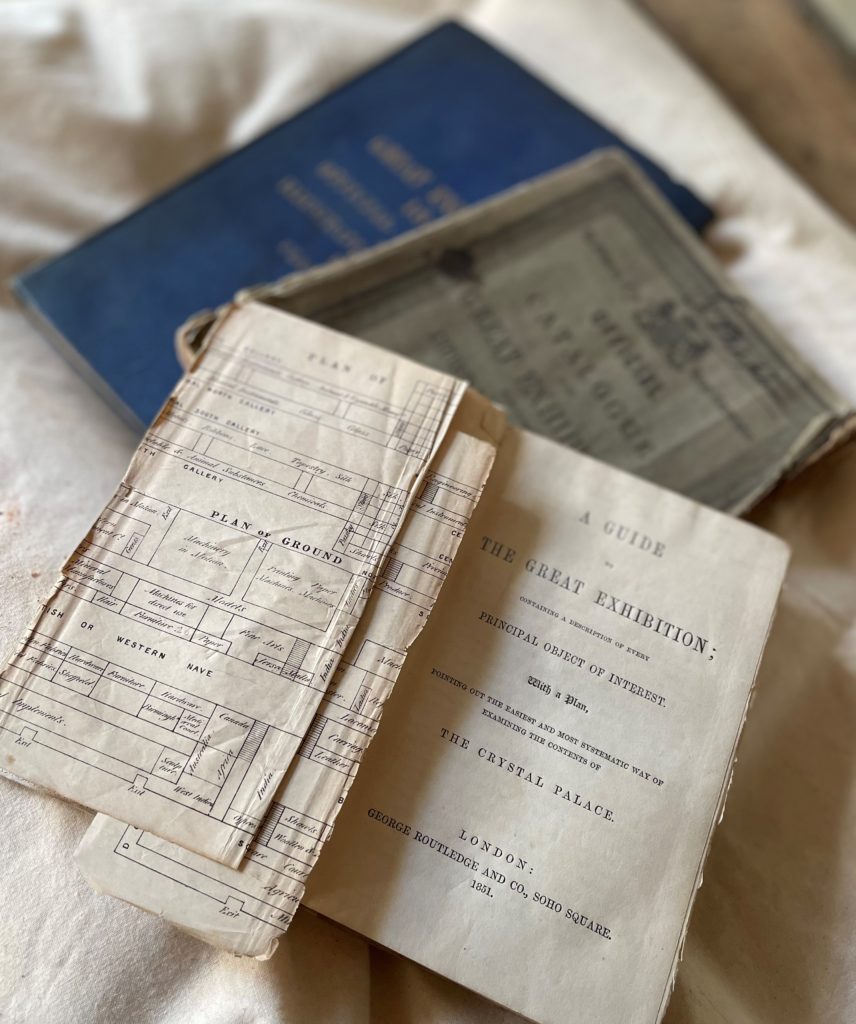

The Great Exhibition offered a guidebook for every budget. The Library at the Devon and Exeter Institution has several, from the heavy, gilt-edged, red leather-bound folios, illustrated with exquisite steel engravings, published by the Spicer Brothers and printed by William Clowes and Sons, to cheap pocket guides in grey paper wrappers with fold-out plans. Members unable to travel to London could also read the special Exhibition issues of the Illustrated London News which contain magnificent fold-out engraved plates, ten times the size of the newspaper.

Surplus funds from the Great Exhibition were used to found the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum), the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum; an educational trust continues to provide grants and scholarships today. From its foundation in 1813, the Devon and Exeter Institution had assembled a collection of artefacts and specimens and, prior to the Great Exhibition, was urged to take the lead in establishing a ‘Museum illustrative of the Natural and Ancient History of Devonshire’ (Western Times, 1 December 1849). Following Prince Albert’s death in 1861, however, Devon MP Sir Stafford Northcote of Pynes (1818–1887), President of the Exeter School of Art and one of Prince Albert’s secretaries for the Great Exhibition, was instrumental in founding the Royal Albert Memorial Museum which held its official opening in August 1869. Artefacts in the early collection at the Devon and Exeter Institution were transferred to the new Museum in Queen Street, and can still be seen there today.

Emma Laws, Director of Collections and Research

Emma is currently undertaking research on Exeter and the Great Exhibition.