“Rough Cyder for Summer’s drinking”: 18th century treatises on Cyder

Treatises on Cider (1755), is a collaborative piece, and is currently on display as part of our “Looking Between the Lines: Marginalia in the DEI Collections” exhibition. It is the result of various writers forwarding new advice, or even intervening to interrupt the directions of the current speaker.

The first extract, entitled “A dissertation on Cyder and Cyder-Fruit,” was written by Hugh Stafford, of Pynes in Devonshire, Esq., (1674- 1734), as part of a “letter to a friend” in 1727. He pays particular attention to the “Royal Wilding apple,” the produce of a “single tree,” which “stands on a very little quillet… adjoining to the port-road that leads from Exeter to Oakhampton.” The walk of “a mile,” he elaborates, “will gratify any one, who has curiosity, with a sight of it.” According to Stafford’s account, the fruit was discovered by Mr Robert Woolcombe, Rector of Whitestone, who was so pleased with the apple he “talked of it in all conversations.” Stafford concurs “I.. am so… perfectly possessed with a persuasion of the excellency of the cyder, that I doubt not in the course of twenty years more, when gentlemen have furnished themselves with the fruit, and farmers have fallen in with it also, this county will be rendered abundantly happy in it.” Moreover, he contends “whatever fruit there may be in nature,… I have never tasted any cyder equal to it.” Stafford’s letter is therefore really an advocation of the virtues of one particular apple, the Exeter-made “Royal Wilding,” with some remarks on the “White Sour,” the Wilding’s only real “competition.”

At the end of Stafford’s letter, a previous reader of the volume makes sure to emphasize that the rest of the printed work is the result of another author’s efforts: “By the title we are informed that the whole of this work is the performance of Mr. Stafford, but it seems that only the foregoing letter is his production, and that the sequel is the work of another person who has not thought proper to put their name to it.” Indeed, the following “treatise on cyder” is simply signed “some Nursery man.” Nonetheless, the anonymous author assumes an authoritative tone: “Having now given Mr Stafford’s remarks, I shall now, without further interruption, proceed to my own. As I would recommend but a few kinds of apples for making cyder, it is necessary that there should appear in the catalogue, only fruits of an established reputation, and whatever is excellent for fruitfulness, quick growth, duration, hardiness, and plenty and goodness of juices.” The following text serves as a kind of catalogue of suitable apples, including “the White-Sour,” “The Elliot,” “The Herefordshire Red-Streak,” and the “Fox-Welp.” Like Stafford, he also includes the “Royal Wilding,” a “beautiful spreading tree, and most abundantly fruitful,” which was “accidentally produced near Exeter.”

In Section II, the anonymous writer evaluates the “Devonshire method” of collecting apples into heaps, and sweating the fruits “to prepare them for a market.” He outlines the method as follows:

- That all the promiscuous kinds of apples that have dropp’d from the trees, from time to time, are to be gathered up, and laid in a heap by themselves, and to be made into cyder, after having lain so about ten days.

- Such apples as are gathered from the trees, having already acquired some degree of maturity, are likewise to be laid in a heap by themselves, for about a fortnight.

- The latter hard fruits, which are to be left on the trees till the approach of frost is apprehended, are to be laid in a separate heap, where they are to remain a month or six weeks, by which, notwithstanding frost, rain, &c. their juices will receive such a maturation, as will prepare them for a kindly fermentation, and which they could not have attained on the trees, by means of the coldness of the season.

The nursery man concludes “by pursuing the above methods, besides making the best cyder, hurry and expence will be prevented, as they require no room within doors.”

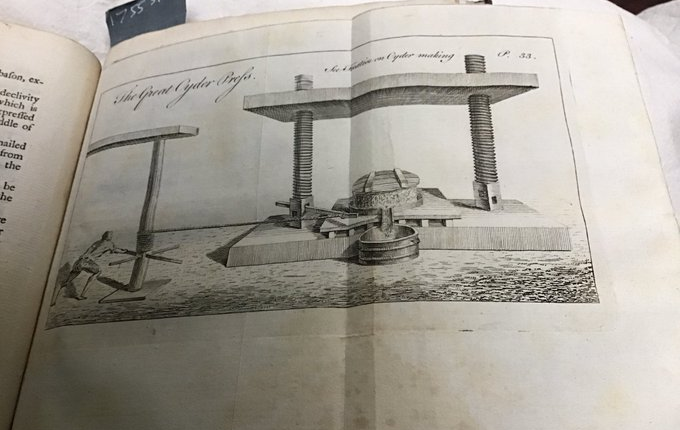

The following sections, (III, IV, and V), the nursery man devotes to the “invention of an Engine,” made by “the People in Devonshire,” which “least bruises the skin, pulp, and kernels of apples.” A fold-out illustration of “The Great Cyder Press” (see above) compliments the account.

The writer proceeds to extend advice on fermenting, racking, preserving, and finally drinking cider, asserting:

“In Devonshire, in rough Cyder for summer’s drinking, it is usual to put either the Leaves or Flowers of Clary, which makes it very nearly imitate Rhenish wine.”

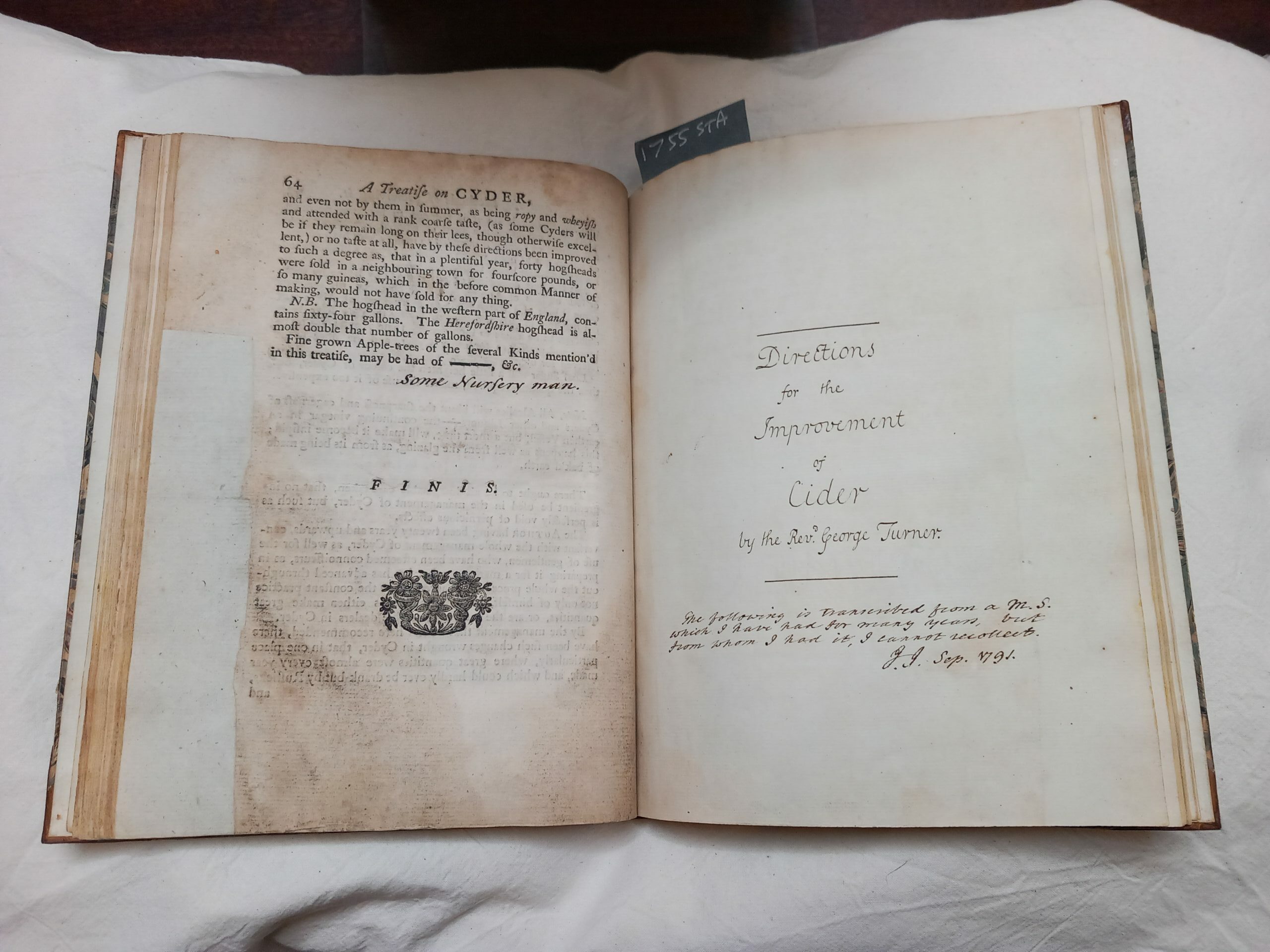

Following the Nursery Man’s guide, a handwritten series of “Directions for the Improvements of Cider,” begins on a new page. Though at first these instructions appear to be from the pen of “the Rev.d George Turner,” the writer acknowledges: “the following is transcribed from a M. S. which I have had for many years, but from whom I had it, I cannot recollect.”

The account, written in a delicate cursive hand, is almost poetic in tone:

“Let all your apples drop, from the tree, that they may have the full benefit of the stock and of the sun.

Let your apples (especially in windy and tempestuous weather) be pickt up once a week, at least, and thrown to a heap in some secure place without door; for hoarding within doors is apt to give the juice a musty taste for want of a free and open air: it also prevents the cider from quick refining.

Let your apple-heap be made on slanting and open ground towards the South that the falling rains may fleet from it, and that your fruit may likewise have the benefit of the air and of the sun.”

However, the writer deviates slightly as he begins not only to “enlarge” on cider’s medical benefits, “as a good diuretick, pectoral and a cooler of the blood when taken in a moderate way,” but also to advocate for cider against “foreign wines.” He concludes by similarly asserting:

“I might observe, by way of postscript, that at this critical juncture, we are obliged in interest as well as for health’s sake, to wean ourselves from French spirits, which, by a sad abuse of speech, some are wont to call Mother’s Milk; for as money is the sinews of war, to waste our treasure in wine and brandy, what is it but running the risque of a double death, by putting a sword into our enemies’ hands to destroy us, and by becoming our own executioners in the use of these pernicious liquors.”

Following this emphatic remark, another text on cider is inserted, written in another hand. The work is entitled “A main and concise treatise on the properties of apples and pears, and quality of their liquors,” and is dated 1799. The author, E. Gardiner, describes himself in his short introduction as “a man that has made cyder and perry his study for more than twenty years,” who “has at last attained a thorough knowledge and method of making these liquors in a manner to be little inferior to the most wholesome white wine.” Like many of the other authors, he attests to cider’s emergent reputation by comparing the drink with other beverages.

Gardiner’s instructions also expand on the advice offered elsewhere across the collection of treatises. He asserts “all fruits, particularly apples and pears, should be left on the trees until they are ripe, that the asperity of their juices may have time, and benefit of sun and air, to become mellow and sweet.” In such a way, this policy of non-intervention echoes Turner’s direction to “let all your apples drop, from the tree, that they may have the full benefit of the stock and of the sun,” and the anonymous nursery man’s advocation of the “Devonshire method,” in which “all the promiscuous kinds of apples that have dropp’d from the trees, from time to time, are to be gathered up, and lain in a heap by themselves, and to be made into cyder, after having lain so about ten days.” Perhaps such methods did indeed foster such great cider-making apples as the Royal Wilding, the favourite of Hugh Stafford. At choice points in this text, new writers patch in to interrupt the previous speaker, but their writings consent much more than they differ.

Treatises on Cyder, (S. W. Cupboard 1755 STA), can currently be viewed in the Outer Library, as part of our “Looking Between the Lines: Marginalia in the DEI Collections” exhibition.