Philip Henry Gosse’s Aquarium (1854)

In May 1852, the marine biologist and naturalist, Philip Henry Gosse (1810-1888), made his first serious attempt to create a marine aquarium. He put three pints of sea water into a glass container with a selection of marine plants and animals and topped up the water from time to time as it evaporated. The contents remained healthy for more than two months. The only tricky thing was preventing the animals from eating each other!

In May 1852, the marine biologist and naturalist, Philip Henry Gosse (1810-1888), made his first serious attempt to create a marine aquarium. He put three pints of sea water into a glass container with a selection of marine plants and animals and topped up the water from time to time as it evaporated. The contents remained healthy for more than two months. The only tricky thing was preventing the animals from eating each other!

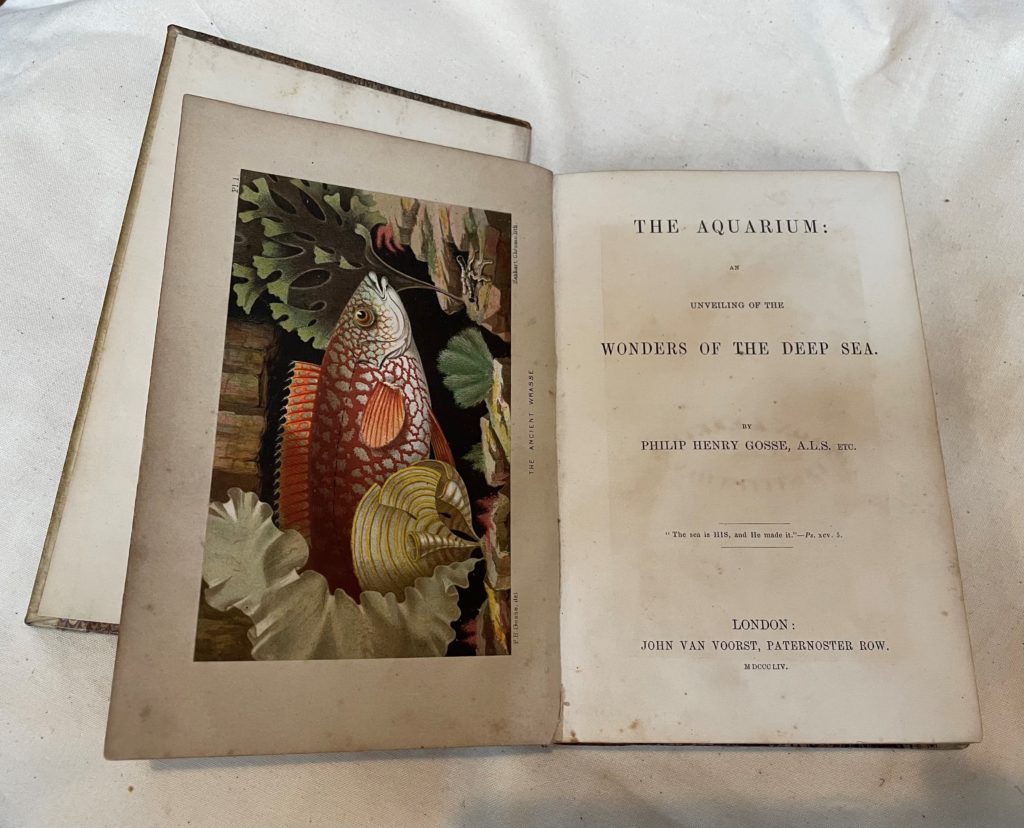

Gosse had been staying with his family in Devon, first in St. Marychurch, a mile outside Torquay in south Devon, and then in Ilfracombe on the north Devon coast. He spent his days gathering marine specimens to collect, identify and illustrate. In early December 1852, Gosse set about building a tank in the new Fish House at the Zoological Gardens in Regent’s Park (now London Zoo), stocked with about two hundred specimens collected in Ilfracombe two months earlier. In April 1853, Gosse again travelled west, this time to Dorset, to collect specimens to send back to the Zoological Society in London. His observations formed the basis of his best-seller, The Aquarium : an Unveiling of the Wonders of the Deep Sea (1854).

Gosse had been staying with his family in Devon, first in St. Marychurch, a mile outside Torquay in south Devon, and then in Ilfracombe on the north Devon coast. He spent his days gathering marine specimens to collect, identify and illustrate. In early December 1852, Gosse set about building a tank in the new Fish House at the Zoological Gardens in Regent’s Park (now London Zoo), stocked with about two hundred specimens collected in Ilfracombe two months earlier. In April 1853, Gosse again travelled west, this time to Dorset, to collect specimens to send back to the Zoological Society in London. His observations formed the basis of his best-seller, The Aquarium : an Unveiling of the Wonders of the Deep Sea (1854).

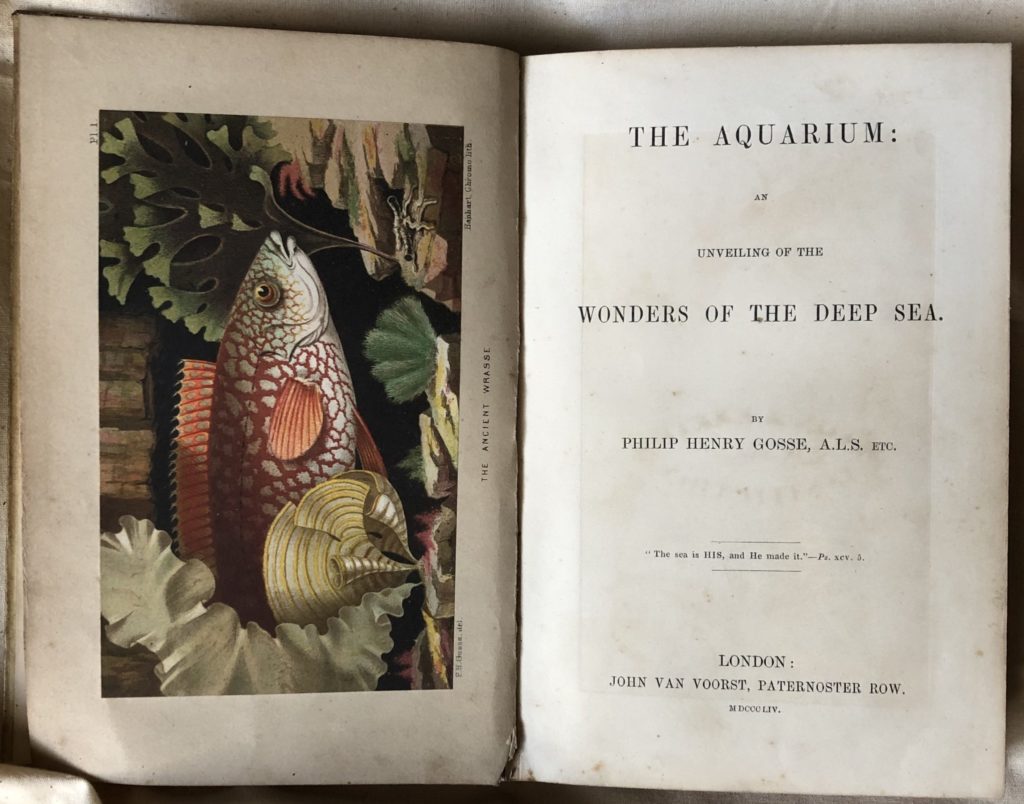

The book sold ‘like wild-fire’ and was ‘lavishly adorned’ with twelve very expensive colour lithographed plates:

I have endeavoured – in a manner hitherto, I believe, unattempted – to represent marine animals, with their beauty of form and brilliance of colour, in their proper haunts, surrounded by submarine rocks and elegant sea-weeds, as these appear when transferred to an Aquarium.

In the final chapter, he offers guidance on setting up an aquarium at home. Within a few years the marine aquarium had become a fashionable ornament of the Victorian parlour; families gathered round to watch the live show and designs for vessels, made from glass, slate, wood and iron, became more and more elaborate. Gosse went on to publish a sequel, A Handbook to the Marine Aquarium, and in 1856 was elected Fellow of the Royal Society. An obituary notice in the Proceedings of the Royal Society 1889 claimed that he was, ‘not only a many-sided and experienced naturalist, but one who did more than all his scientific contemporaries to popularize the study of natural objects’.