Mayflower: marking 400 years

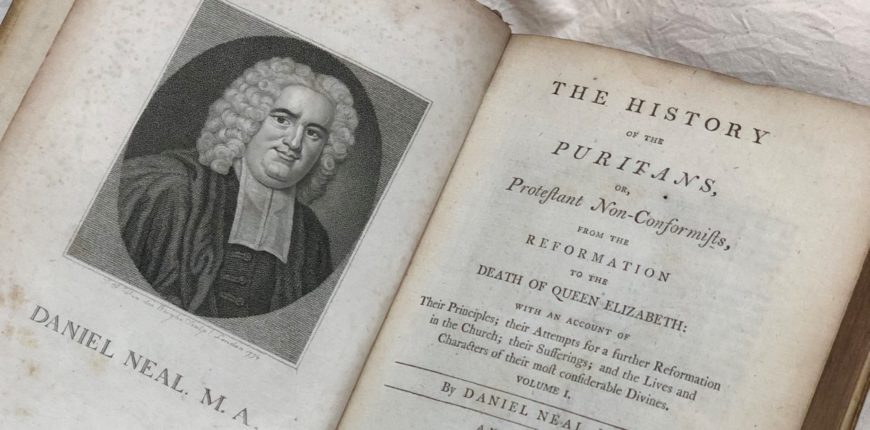

Daniel Neal (1678-1743), a historian and nonconformist minister, published the first volume of The History of the Puritans in 1732; the final fourth volume appeared in 1738. Neal’s story starts with the Protestant Reformation and concludes with the Act of Toleration in the reign of William and Mary. The second volume includes an account of the voyage of Mayflower to the new ‘Promised Land’.

Mayflower set sail from Plymouth on 16th September 1620. Bound for America, she promised her passengers a new life of religious freedom, adventure, and economic prosperity.

Daniel Neal (1678-1743)

The English Puritans wanted to ‘purify’ the Church of England from its Roman Catholic practices. In 1608, many fled persecution in England to establish a new community in The Netherlands, a country with a reputation for religious tolerance. They settled in Leiden in Holland and were supported and encouraged by John Robinson (1576-1625), a strong critic of the Church of England, often referred to as the ‘pastor of the Pilgrim Fathers’. However, it was not long before members of the congregation in Leiden looked to make another new start. Life in Leiden was poor, and their congregation was dwindling:

‘Among the Brownists in Holland we have mentioned the reverend Mr. John Robinson, of Leyden, the father of the independents, whose numerous congregations being on the decline, by their aged members dying off, and their children marrying into Dutch families, they consulted how to preserve their church and religion; and at length, after several solemn addresses to heaven for direction, the younger part of the congregation resolved to remove into some part of America, under the protection of the king of England, where they might enjoy the liberty of their consciences, and be capable of encouraging their friends and countrymen to follow them.’

The Puritans originally commissioned two ships for the voyage: Speedwell was to carry members of Robinson’s congregation from Leiden and Mayflower was to sail from London with ‘necessaries for the new plantation’. The two ships were to meet in Southampton and cross the Atlantic together.

Speedwell set sail from Holland on 22 July 1620. Daniel Neal offers some account of the moving ceremony conducted by John Robinson who ‘kneeled down on the sea-shore, and with a fervent prayer committed them to the protection and blessing of heaven.’ (The remaining congregation in Leiden subsequently declined; John Robinson never made it to America but his son, Isaac, arrived in the new Plymouth colony in 1631.)

Speedwell began taking in water on her journey from Holland but following repairs in England both ships set sail from Southampton on 15 August. Again, Speedwell sprung a leak and the two ships were forced to divert their course and return to Plymouth. Mayflower would make the journey alone. Passengers from Speedwell joined those on board Mayflower; however, after more than a month at sea already, some inevitably decided not to continue to America.

Mayflower set sail from Plymouth a month later. Her passengers were broadly divided into Saints (those seeking religious freedom) and Strangers (those looking for adventure and economic prosperity). The ship anchored at Cape Cod on 11 November 1620. Daniel Neal writes in some detail of the hardships they faced in their new ‘Promised Land’:

Mayflower set sail from Plymouth a month later. Her passengers were broadly divided into Saints (those seeking religious freedom) and Strangers (those looking for adventure and economic prosperity). The ship anchored at Cape Cod on 11 November 1620. Daniel Neal writes in some detail of the hardships they faced in their new ‘Promised Land’:

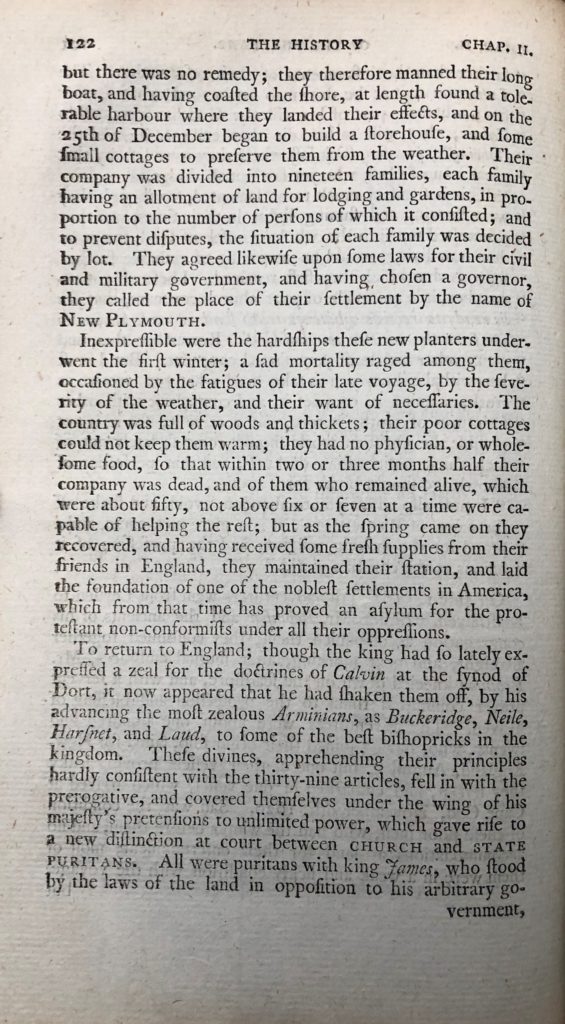

‘Sad was the condition of these poor men, who had the winter before them, and no accommodations at land for their entertainment; most of them were in a weak and sickly condition with the voyage, but there was no remedy; they therefore manned their long boat, and having coasted the shore, at length found a tolerable harbour where they landed their effects, and on the 25th December began to build a storehouse, and some small cottages to preserve them from the weather. Their company was divided into nineteen families, each family having an allotment of land for lodging and gardens, in proportion to the number of persons of which it consisted; and to prevent disputes, the situation of each family was decided by lot. They agreed likewise upon some laws for their civil and military government [the Mayflower Compact], and having chosen a governor, they called the place of their settlement by the name of New Plymouth.

Inexpressible were the hardships these new planters underwent the first winter, a sad mortality raged among them, occasioned by the fatigues of their late voyage, by the severity of the weather, and their want of necessaries. The country was full of woods and thickets; their poor cottages could not keep them warm; they had no physician, or wholesome food, so that within two or three months half their company was dead, and of them who remained alive, which were about fifty, not above six or seven at a time were capable of helping the rest; but as the spring came on they recovered, and having received some fresh supplies from their friends in England, they maintained their station …’

The colonists celebrated their first harvest in 1621 with a three-day festival of prayer; Thanksgiving remains a national holiday in America.

Daniel Neal claims that the Puritans ‘laid the foundation of one of the noblest settlements in America, which from that time has proved an asylum for the protestant non-conformists under all their oppressions.’ Alas, this is not entirely true. The Puritans proved just as intolerant of differences in religious practice as those who had forced them to flee England in 1608. Quakers were among those persecuted in the new colony – Edward Burrough (1634 – 1663), a Quaker preacher, describes their brutal treatment in A Declaration of the Sad and Great Persecution and Martyrdom of the People of God, called Quakers, in New-England, for the Worshipping of God (1661).

Other voices, too, have been excluded from the Mayflower story over the centuries. The Wampanoag, and other Native American tribes, who had lived on the land for thousands of years before the arrival of the colonists were struck down by European diseases for which they had no immunity. Worse, thousands of Native Americans were killed or sold into slavery.

This year, the Wampanoag join the UK, USA and The Netherlands to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower’s crossing. More details are available on the Mayflower400 website (https://www.mayflower400uk.org/education/native-america-and-the-mayflower-400-years-of-wampanoag-history/):

‘The words “we are still here” echo through this anniversary, as does centuries of Wampanoag history and the voices of those determined to keep the stories of their ancestors alive through a series of commemorative projects, exhibitions and events.’

The Devon and Exeter Institution’s copy of Daniel Neal’s History of the Puritans, or Protestant Non-Conformists is the new edition of 1793, edited by Joshua Toulmin (1740-1815), a West Country nonconformist minister. Toulmin began his career at a Presbyterian congregation in Colyton, East Devon, before moving to a Baptist congregation in Taunton, Somerset and then to a Unitarian congregation in Birmingham. His History of Taunton in the County of Somerset was published in 1791. The full text of Daniel Neal’s account of the Mayflower story is available online: https://archive.org/details/historyo02neal

Emma Laws

Director of Collections and Research