Mary Bulteel Ponsonby, a Radical Maid of Honour to Queen Victoria

For November’s Book of the Month our volunteer cataloguer Paul Auchterlonie appraises an unusual find from the travel section, detailing the life of Mary Ponsonby, (1832-1916), a woman who lived a rich and unusual life at the Court of Queen Victoria.

When I was going through the Geography and Travel Section for the Collections Review, I came across a book which seemed out of place there: Mary Ponsonby: a Memoir, Some Letters and a Journal, edited by her daughter Magdalen Ponsonby (London: John Murray, 1927: G 21). Looking at its content, it painted a portrait of a woman who also seemed out of place in the rather stuffy conservative court of Queen Victoria. So, I decided to investigate with the help of a recent donation, Henry and Mary Ponsonby: Life at the Court of Queen Victoria, by Michael M. Kuhn (London: Duckworth, 2002: AB 92 PON/K). This book, perhaps surprisingly, but refreshingly and entirely appropriately, devotes as much space to Mary Ponsonby’s life as it does to that of her husband, Henry.

Mary Bulteel was born in 1832 at Lyneham House, a country house near Yealmpton in the South-West of Devon, but the family moved to the nearby but grander house of Flete, near Holbeton in 1837. The Bulteels were of Huguenot origin, but had been established in Devon since the 1620s; they were also connected with the aristocracy, and Mary’s grandfather was Lord Grey, who had brought in the Great Reform Act. In 1843, Mary’s father died and she moved with her mother and sisters to a house in Eaton Square, London. Although not well-off, the Bulteels were connected to some of the richest families, and Mary spent a lot of time at Woburn Abbey and Wrest Park, where she and her friends ‘acted, danced, flirted and enjoyed ourselves’. When she was twenty, she went on a visit to her uncle General Grey, who was private secretary to Queen Victoria, to whom she was presented. Victoria took an immediate liking to her because of her interest in acting and music and made her a Maid of Honour. Mary’s daughter Magdalen suggests that ‘they attracted each other, not because they were alike, but because they were startlingly unlike’. While she was young, Mary was in the grip of a religious fervour and wanted to join or even found an Anglican order of nuns. She wrote that when she joined the court, she ‘was rather odious … I found the Court atmosphere exceedingly dull. I am sure I was rather superior and pompous … [and] I made strenuous efforts to keep up a high standard of religious practice.”

However, she also made the first of a long line of female friends at court, in particular Lady Margaret Canning and Lady Frances Jocelyn, both Ladies in Waiting. She also made friends with Magdalen ‘Lily’ Wellesley, wife of Gerald Wellesley, Dean of Windsor, and “Lily showed her what it was like to live a deeply Christian life without shutting oneself away in a cloister”. Her reading also coloured her views; brought up as a Liberal, she was influenced by John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty (1859: I 26.7) and the works of George Eliot (whose letters show a significant correspondence with Mary: D 9.2-4). In 1855 she rejected marriage to the future Chancellor and Home Secretary William Harcourt because of his ‘religious heterodoxy’ (‘1855 was the most exciting, the most disappointing, the happiest and the most miserable year of my life’ she wrote in retrospect). In 1860 she gave up her position as Maid of Honour when she married Henry Ponsonby, who was a colonel in the Grenadier Guards and equerry to Prince Albert (and from 1870 private secretary to Queen Victoria which kept Mary close to court circles). During the 1860s she lived in Canada, Ireland and London, had five children (the youngest, Arthur Ponsonby, became a Labour MP), and briefly had an intense friendship with Agnes Courtenay, the daughter of the Earl of Devon. She was also very active in her concern for justice and equality. She was a member of the committee which set up the first women’s college in Cambridge, Girton, and contributed both her time and her money to this cause, particularly in the early 1870s. She also joined both the general and the executive committee of the Society for the Employment of Women on 1867, and remained on both for thirty years. An advocate of education for women, Mary supported Elizabeth Garrett (as she then was) as a candidate for the London School Board, and when Mary fell ill in the 1890s, was determined that Mrs. Garrett Anderson (as she had become, the first women to qualify as a physician and surgeon in Britain), would be her doctor.

However, her views changed over the decades. In religious terms, she gradually abandoned her enthusiasm for High Church Anglicanism, helped in part by her correspondence with the agnostic, George Eliot (‘I thought that to speak to her of all that was lying deepest in one’s heart and mind without reserve, and to be received in the kindest and most sympathetic way was a rare delight’.). She also became interested in ‘molecular physics and evolutionary biology,’ corresponding with Thomas Henry Huxley, one of the leading scientist of the late Victorian age, and taking a great interest in the work of Marie Curie. However, she still enjoyed the music and ritual of the church, and felt that George Eliot did not always take account of spirituality. She had always been influenced by the work of the French religious philosopher Blaise Pascal, who ‘taught her how a life sternly devoted to loving God might destroy self-love’. She wished to write a book about him but felt that by 1901 she was too old for such a vast undertaking, contenting herself with writing an article on him in 1903 for the periodical Nineteenth Century (Bay 37). Although still believing in justice and equality, she also moved somewhat to the right, disagreeing with her husband over the significance of the death of General Gordon in 1885, and with Gladstone’s home-rule policy, which she felt would lead to the ‘dismemberment’ of the British Empire. She also had a public but not acrimonious correspondence with H.G. Wells about the nature of socialism, a subject on which she wrote an unfinished and unpublished article (she was influenced by the French utopian socialists Fourier and Saint-Simon).

After her husband’s death in 1895, her biographer, Michael Kuhn, wrote ‘In the last two decades of her life, the flame of MP’s passions burnt very hot. In her sixties, she began a triangular friendship with two women who broke down the barriers of reserve and reciprocated her affection with an intensity she had not expected.’ These two women were Ethel Smyth, the very accomplished musician who composed the suffragette anthem, ‘The March of the Women’ and Violet Paget, a forgotten but in her time, popular author who wrote as Vernon Lee. Ethel Smyth wrote that her ten years with Mary Ponsonby, were ‘the happiest, the most satisfying and for that reason, the most restful of all my many friendships with women’.

Before her death in 1916 at the age of 84, she also wrote nostalgically about women in two articles in the Nineteenth Century, not about their rights and education, but about the decline of the great salons, run by the great political and cultural hostesses of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. She argued that ‘noblewomen at Versailles, or in mid-Victorian Mayfair, had more power, position and place than modern women did in the year 1900’. She also supplied the notes for Edmund Gosse’s article on Queen Victoria which appeared in the Quarterly Review in 1901, ‘the first critical piece on the queen to be based on privileged, inside information.’

Mary Ponsonby was, in the words of Lady Constance Lytton, ‘an unusually clever and cultivated woman’. She had known fervent religious belief only to lose it gradually over time. She had worked for equality and justice particularly for women, but regretted the decline of the salons run by the great women of the time. She felt superior to many of her contemporaries, but was determined not to show off, as her self-examination diaries show. She embraced both socialist and conservative beliefs, and wrote about both. She was a devoted wife and mother, but developed a wide array of intense friendships with women. So, a complex, difficult, passionate human being, whose diaries and letters give us a fascinating insight into the concerns, philosophical, political and cultural, of a very well read, intellectual and dynamic Victorian woman.

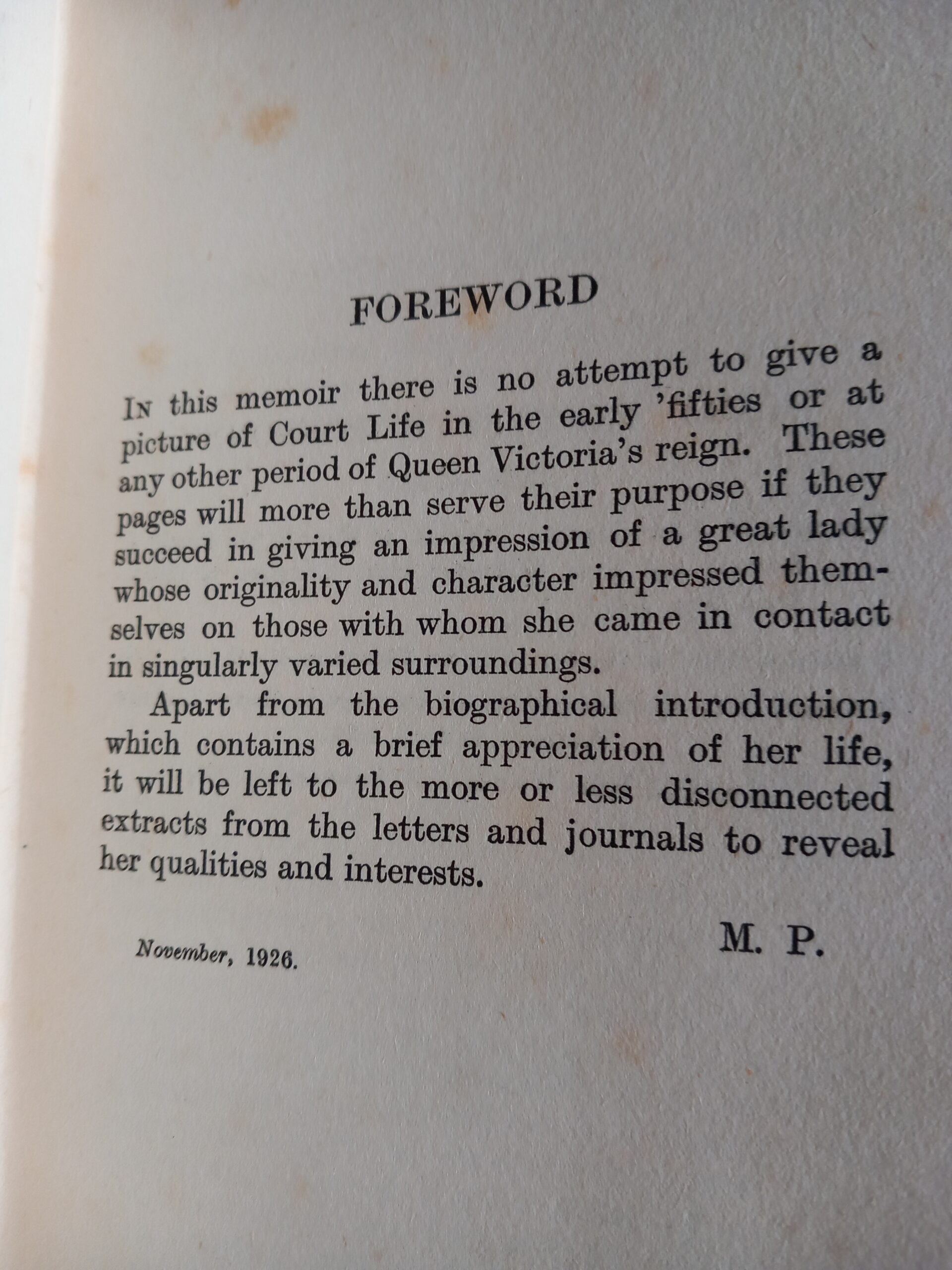

Foreword to G. 21 Mary Elizabeth Bulteel Ponsonby, Mary Ponsonby: A Memoir, some letters, and a journal, (1927)

by Paul Auchterlonie, Volunteer cataloguer.