“I Will Never Consent” – Enys Tregarthen’s Powerful Padstow Mermaid

Mermaids are woven throughout South-Western folklore, but are rarely considered as "hidden histories" of marginalised figures. In this Book of the Month blog one of our volunteers, Becky Rae, explores Enys Tregarthen's fascinating forgotten tale, "The Legend of Padstow Doombar."

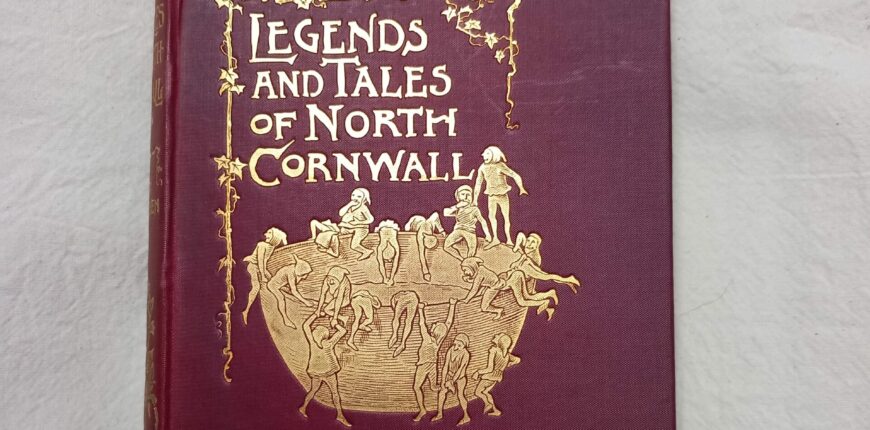

Whilst undertaking research for this year’s summer exhibition in the outer library — “In the roar of the sea,” an appropriate Southwest seaside theme for summertime — I came across a particular folktale and mysterious author who simply had to be included. Gilded lettering on a maroon spine caught my eye as I was browsing the shelves of Bay 54, looking for another book entirely, but the siren song pulled me in and before I knew it, I was diving into the depths of North Cornwall Fairies and Legends [alternative title Legends and Tales of North Cornwall] by Enys Tregarthen, a pseudonym of Ellen (Nellie) Sloggett, a Padstow born authoress and ‘fairyist’. Published in 1906 by Wells Gardner, Darton & Co. LTD in London, its over century-old delicate pages, replete with pretty black and white illustrations and evocative photographs of the North Cornish coast drew me in further, bewitching me with its sense of place, history, and fairy lore.

Despite having published eighteen books over her literary career, under both the folklorist Tregarthen penname, and an earlier alias of Nellie Cornwall, the DEI holds only one copy from Nellie’s oeuvre; perhaps the most important in terms of her position as the only published collector of folklore from North Cornwall. Of the thirteen tales within the collection, five feature ‘Piskeys’, perhaps Nellie’s best known folk creatures (The Piskey Purse was her favourite and most popular book; even Queen Mary had read Tregarthen’s work to her children. Close to pixies in size and stature, Cornish Piskeys were known to be both kind and mischievous: “when the cottages looked very clean and neat it was said that the Piskeys had done it” but that they also flew through keyholes and “ate up all the good” with a “special liking for junkets and sugar biscuits.” As to their origins, Nellie notes that granfolk used to say they were “spirits of still-born and unbaptised children”, who had “wistful moments and yearnings for higher things”, listening “at windows and doors when Christian prayers were being said.” Despite this reference to Christianity harmoniously co-existing with the supernatural, Dr Simon Young notes that there is a ‘jarring lack’ of religion in her writings as Tregarthen, given her earlier Nellie Cornwall sermonic stories, which featured moral tales preaching the importance of Christianity to younger readers (Young: 2017). For someone who had previously lectured these religious themes so heavily, this change in Nellie’s attitude by the early 1900s is perhaps linked to the rise in popularity of theosophist circles and spiritualism, reviving belief in fairies and the like (exemplified by the incident of the infamous Cottingley photographs.) Indeed, Marjorie Johnson, who ran the Fairy Investigation Society received a letter from a woman who had been friends with Nellie: ‘ “Often” wrote Agnes “when I visited [Nellie], she saw fairies on my shoulders.” ’(Johnson: 2014)

Of course, it wasn’t the Piskeys I was really interested in; looking for a companion piece to exhibit alongside Eileen Molony’s The Mermaid of Zennor, with stunning illustrations by the artist and theatre designer Maise Meiklejohn, I found another mermaid tale in Tregarthen’s collection, The Legend of Padstow Doombar, in which an arrogant, violent young man finds his murderous actions have terrible consequences, resulting in a mermaid cursing the previously-safe harbour of Padstow to a perilous stretch of sand that would cause many a shipwreck. Molony’s pairing with a woman illustrator, Meiklejohn’s name a highly-likely selling point of the 1946 publication by Edmund Ward, Leicester, mirrors Tregarthen’s collaboration with her illustrators, which she credits in the opening pages to three women: Miss Ivy Fox, Miss Preston, and Miss M. Forbes— although it’s not stated which illustrations belong to which artist. There are also several black and white photographs scattered throughout, referencing North Cornish landmarks pertinent to each tale; these are all supplied by men, reinforcing the notion that creativity during the late Victorian and early Edwardian era had gendered mediums and spaces (indoor drawing was an acceptable pastime for women, landscape photography which required strength, free leisure time and a sense of adventure/outdoor knowledge was a pursuit for men and men alone. Of the fifty-four photographers currently listed on the Carte De Visite website, only one is a woman— a Mrs. Emma Exley, one of the first women to have her own photographic studio in England. If women did engage in photography, it was most likely portraiture, such as the eponymous Julia Margaret Cameron.)

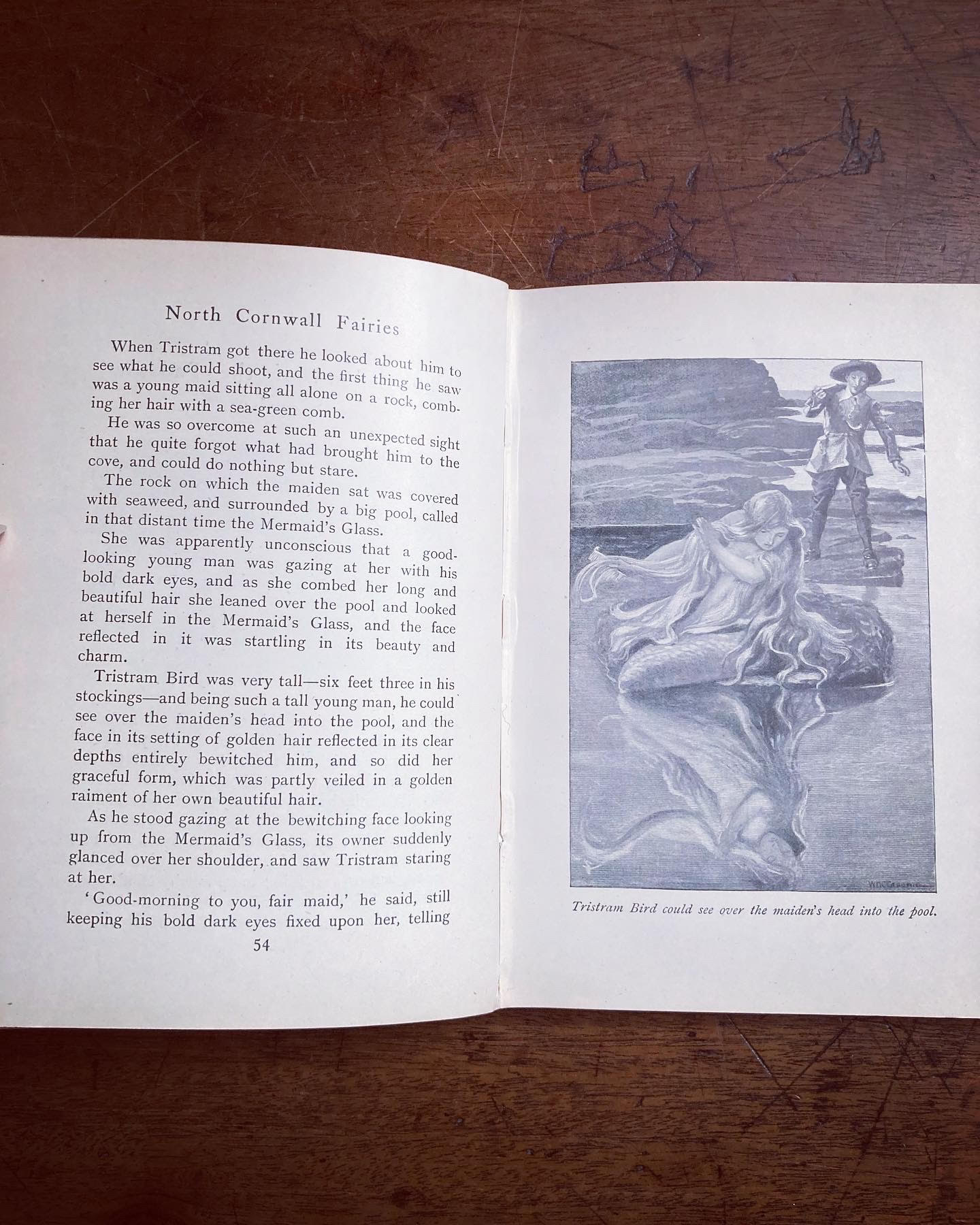

Similarly to Molony’s retelling of the Zennor tale, the merwomen in both Cornish legends have a high level of independence and are seemingly romantically unattached and unincumbered by societal restraints on their behaviour (Molony’s mermaid essentially kidnaps a young choir boy and Tregarthen’s mermaid refuses to marry a man who repeatedly proposes to her.) I was particularly struck by the theme of empowered consent in Tregarthen’s folktale; unlike the other female characters portrayed throughout the collection, with simple commonfolk wives and mothers tied to their domestic and communal duties, her mermaid is liberated from such moral and practical burdens, instead preferring to spend her time akin to Narcissus, combing her long golden hair and gazing out over her own beautiful reflection in a pool of water known as the Mermaid’s Glass. It is here that the young Tristram Bird, on the hunt and desperate for something to shoot to impress the ladies back in Padstow, birds and seals no longer satiating his bloodlust, finds our mermaid— her tail hidden from sight under the water surrounding the rock she sits upon:

“She was apparently unconscious that a good-looking young man was gazing at her with his bold dark eyes, and as she combed her long and beautiful hair she leaned over the pool and

looked at herself in the Mermaid’s Glass, and the face reflected in it was startling in its beauty and charm.”

From the start, then, we are told how unpreoccupied she is at the presence of a man, one who struggles with this concept throughout in a constant bid for her attention and affection. What strikes me as interesting is that we have all the ‘red flags’ of misogynistic and abusive behaviour that 21st-century women are well-versed in but in a text of 1906; within moments of meeting her, he is commenting on her appearance, showering her with compliments and telling her that he loves her (what would now be described as love-bombing.) But Tregarthen’s mermaid isn’t turned so easily – she mocks Bird throughout with a knowing scorn: ‘ “It does not take a man of your breed long to fall in love,” said the beautiful maid, with a toss of her golden head and a curl of her sweet red lips.’ Bird’s confusion at her apathy pushes him further, insisting how much of a ‘catch’ he is, and demanding that she give him a lock of her hair to wear above his heart. She refuses, calling him a ‘landlubber’, to which he takes offence, claiming, “one would think you were a maid of the sea!” Even when she has confirmed this, he ignores the “warning look in her sea-blue eyes” as she speaks of cursing the harbour and demands that she marry him given what a fine home he has. But Tregarthen’s mermaid is as uninterested in material possessions and wealth as she is in him: “Let me tell you once and forever I would not marry you if you were decked in diamonds and your house a golden house.”

Humiliated and aggrieved that a woman should treat him with such casual neglect and refuse his advances, comes the inevitable switch from the ‘nice guy’ to the cruel entitled misogynist: “You have bewitched me, sweet, and no other man shall have you. If I can’t have you living, I’ll have you dead.” It seems a shocking line within the context of a book of family-friendly folktales, and yet given that over a hundred years later, in 2023 two women are killed by domestic violence on average every week in the UK (most often by a current or ex-partner), this theme of ‘if I can’t have you no one will’ is as common now as it was at the time of Tregarthen’s writing. Indeed, Bird’s entitled behaviour and murderous threats— which he of course acts out, thus igniting the curse of the Doombar— reeks of what would now be described as incel culture, (a mass shooting that took place in Plymouth in 2021 follows this exact pattern of behaviour). While we may still suffer the Tristram’s of the world, what struck me as a reader is her mermaid’s resolute courage and conviction in saying no: ‘ “I will never consent,” she said.’ Our merheroine would rather die than give up her independence, individualism, and liberation from gendered society that her watery world offers her.

It is interesting that instead of simply diving into the water and swimming away, Tregarthen’s mermaid refuses to move from where she sits, and her tail is unseen by Tristram until after he has shot her dead. While we might read this as an empowered choice —I was here first, why should I have to leave?— another reading is through the lens of disability Nellie herself might have felt. As a teenager, (sources differ on the exact age), Nellie became paralysed from the waist down, an affliction she would live with for the rest of her life, keeping her bedbound and unable to physically explore many of the Cornish landscapes she wrote about: ‘ “The little cripple”, as she was known in her home town (Yates: 1940), had suffered, in her teens, from an illness that had left her paralysed. From the onset of this illness to her death at 73, she never took a step. Indeed, she spent most of her life prone, looking out over “Padstow’s storied land and water” (Wright: 1978): “the Camel River to the St. Minver sand hills” on one side of her bed, and “the rocky tors of Bodmin Moor” (Yates: 1940) on the other.’ (Young: 2017) Like her mermaid, it is probable her lower half was consistently covered, and she would not have been able to get up and leave at her own free will. Instead, she wrote “from her bed, leaning on one elbow and holding a pencil in her other hand.” (Yates: 1959)

Perhaps it was not Nellie’s intention to offer up such a boldly feminist figurehead at the time— we do not know, for example, if she was a supporter of Women’s Suffrage— but I can only imagine what hopes and dreams tales of such radically liberated merwomen might have inspired in female readers of the early 1900s. What is wonderful to see now is the rightful recognition of Nellie’s work as a disabled woman author and folklorist alongside her male counterparts; the recording of Cornish folklore has for too long been solely attributed to Robert Hunt and William Bottrell, but as Young states ‘Hunt and Bottrell dealt predominantly with the west of the county’ while ‘Nellie concentrated on the little-investigated northern coast and partially plugged a gap in our knowledge.’ (Young: 2017) In a recent lecture, Young called for a blue plaque to be instated in her name, and she was featured by Cornwall Council for International Women’s Day March 2023. She is also currently highlighted alongside a number of other distinguished women in the 2023 Women of Cornwall exhibition at Kresen Kernow, and with a recent resurgence in popularity of mermaid lore (Disney’s live action version of The Little Mermaid was released in May, and Florence + The Machine’s Mermaids track in April) what better choice was there than Nellie’s powerful mermaid of Padstow to swim the stacks with.

by Becky Rae.

[Citations and further reading:

Dr Simon Young’s Enys Tregarthen of Padstow: A Neglected Cornish Folklorist and Fairyist was published in May of this year, and I am indebted to his article “Her Room Was Her World: Nellie Sloggett and North Cornish Folklore” which appeared in the 2017 Journal of Ethnology and Folklorisitics (11 (2): 101–136). The numerous citations included above were taken from the aforementioned paper. A copy of North Cornwall Fairies and Legends can be read on Project Gutenburg here.]