Annotating Alice: An Exam-Season Special Collection Highlight

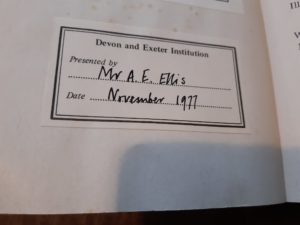

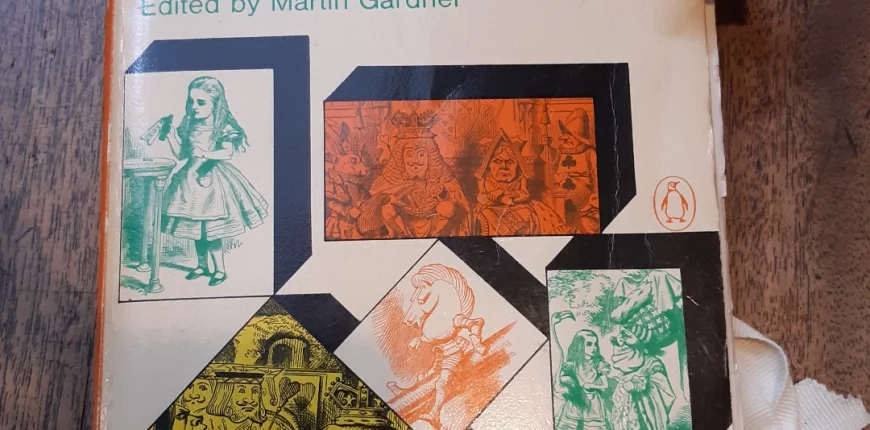

January is exam season, and we would like to extend wishes of good luck to our student members, many of whom have been revising and studying here over the last few weeks. Of course, studying a subject in great depth, though a chore to some, can also provide a source of great interest. This certainly appears to be true in the case of a Mr A. E. Ellis, a dedicated fan of the “Alice” books, who donated his copies of Rhyme? and Reason? (1913), The Lewis Carroll Picture Book (1919), The Complete Works of Lewis Carroll (1966), and The Annotated Alice (1965), in 1977, with “copious additions, annotations and inserts,” as our catalogue entry for the volume indicates.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), and Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found there (1871), have been popular since their original publication, amongst children and adults. Partly, the appeal of the “Alice” books can be attributed to Carroll’s clever satire on the culture of rote learning, and a hope for the scope of the imagination beyond cold hard facts. At various points throughout the books, Alice forgets or substitutes lines of poetry that she has been taught at school, or worries that she is disobeying instructions. Her ability to get out of Wonderland, and later, out of the Looking Glass, nonetheless relies on her capacity to think creatively, to interact with the creatures around her, and to glean the information she needs.

It seems it was in a similar spirit of curiosity and creativity that our generous donor, A.E. Ellis, was acting in 1977. In his copy of The Annotated Alice in particular, notes, postcards, slides and images are pasted and inserted into the text, providing extra information about Lewis Carroll’s world of influence and his creative process. Our Mr. Ellis clearly made several trips to Oxford, and pasted in a 1969 slide from the Museum of the History of Science, and a postcard depicting the remains of a dodo in the Ashmolean.

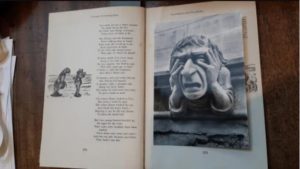

Tracing the inspiration behind Carroll’s maddening Duchess character, he includes a print of the Quinten Massys’ 16th century painting of “A Grotesque Old Woman,” which bears an uncanny resemblance to John Tenniel’s illustrative interpretation of the curious hatted figure. Ellis also includes extensive notes regarding the carving of a hare with a satchel in The Church of St Mary, Beverley, where Lewis Carroll stayed with friends. Portraits of the writer himself are interspersed at several points. On the back of a carving at New College, Oxford, Ellis asks: “Is this the model for Tenniel’s carpenter?”

A little battered and well-thumbed, Ellis’ volume of the text was clearly loved, but is also testament to the idea that a volume can have many lives, and many readers. Like many texts, it has been heavily perused for information, and has hallmarks of the ideas and notes of its one-time owner. One thing is certain, in the event of an exam on Alice, our Mr. Ellis would have done very well indeed.