A Touch of Ireland— A Book Display for St Patrick’s Day

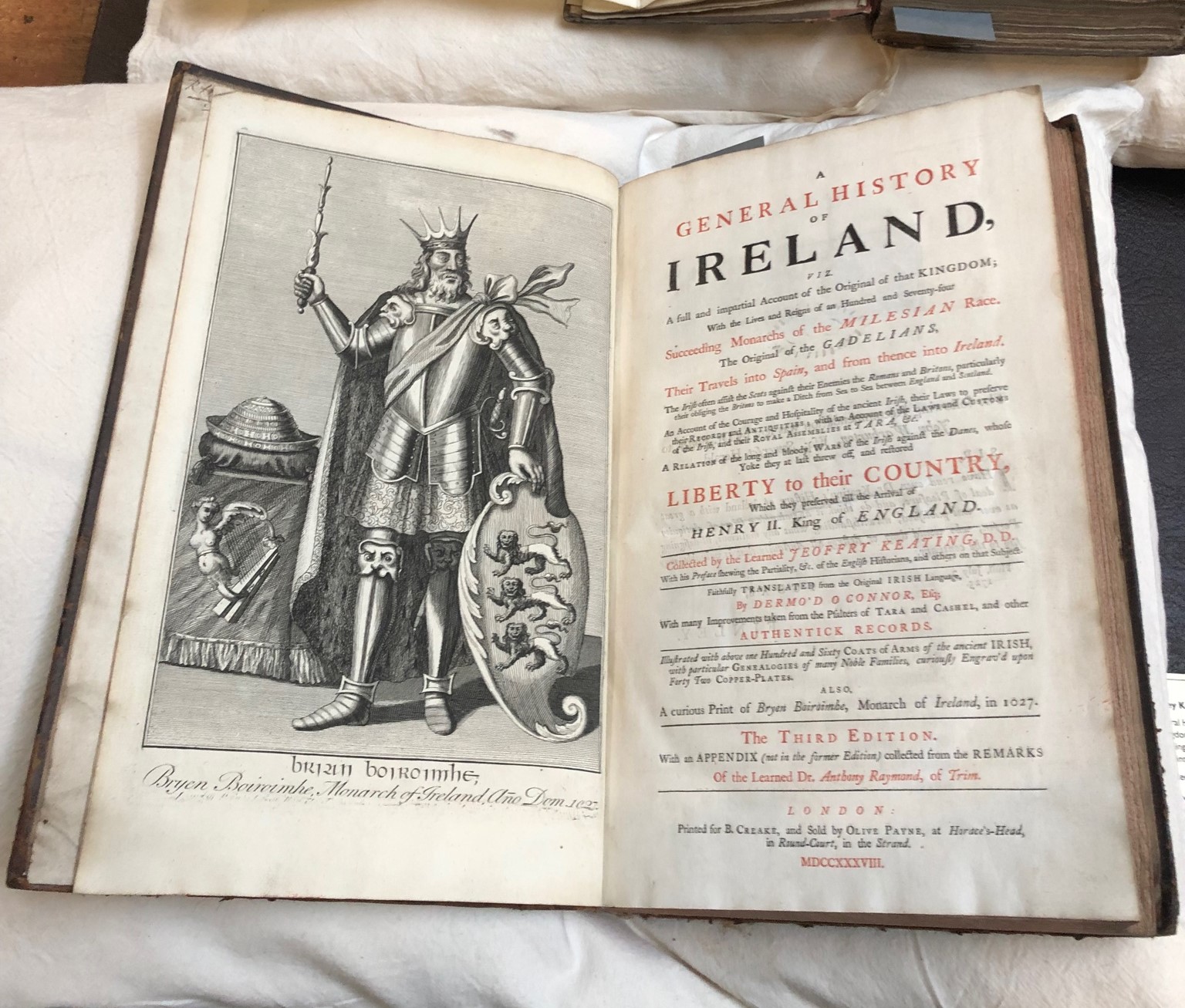

For St. Patrick’s Day this year we decided to draw on some items in the collection which relate to Ireland in some way. Some texts were written by Irish authors while others were written by English authors who were interested in Ireland. St. Patrick, the Irish patron saint, is thought to have brought Christianity to pagan Ireland c.432. It is said that the famous shamrock symbol, which is widely associated with this holiday, was used to explain the holy trinity of the father, the son, and the holy spirit. The Irish adopted Christianity in the centuries which followed, but also retained their Celtic traditions and heritage. Though theological in origin, St. Patrick’s day is today regarded more as a celebration of Irishness and Irish heritage amongst a massive Irish diaspora. One hundred years after Irish independence and the founding of Northern Ireland, this national holiday empowers people from a multitude of backgrounds to embrace Irish traditions.

Of course, for about half of the Devon and Exeter Institution’s lifetime, Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom. Those who were members for the first 119 years may have observed the ongoing agitation that was taking place across the Irish sea. The people of Devon may have drawn interest in the long-standing history between their county and Ireland. In 1591, Fitzgerald castle in County Limerick was granted to the Earls of Devon, who renamed it Devon Castle, during the Munster plantation. In 1910, the absentee landlords sold the property to their agents, the Curling family. It was later burned down during the Irish civil war. In addition, the Irish Famine of the 1840s saw millions of people emigrate to Britain, many of whom ended up in Devon or travelled through Devon to get to industrial cities where they could find work. It is conceivable, then, that the ‘Irish Question’ was contemplated at various times in Devon and Exeter. The purpose of this display was to therefore touch on what conversations may have been happening in the DEI during these periods. Can the books which were acquired relating to Ireland shed some light on the members’ perceptions, or do they simply reflect a wider interest in learning about other cultures?

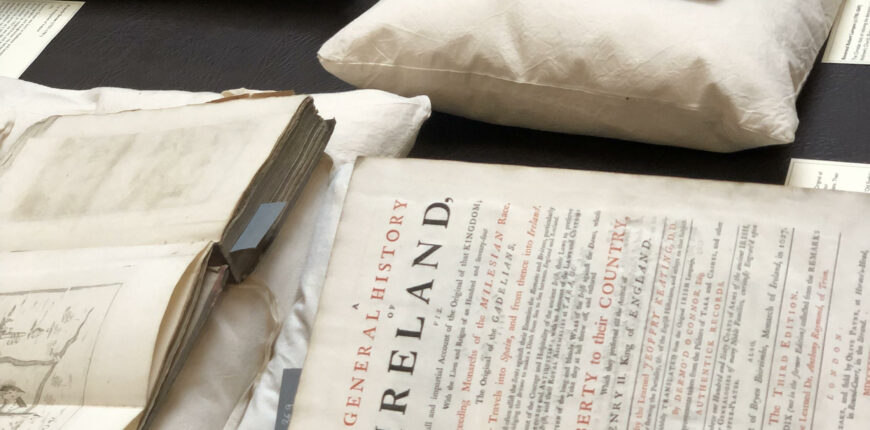

Patrick Weston Joyce (1827-1914)

The origin and history of Irish names of places, (1871)

Joyce was one of eight Catholic children born in the Ballyhoura mountains between Limerick and Cork. He became a teacher as an adult and was selected in 1856 by the Commission of National Education to help reorganise the national school system. He would go on to receive a BA and MA from Trinity College Dublin. In his lifetime, he worked tirelessly as an educationalist, historian, linguist, and writer of Irish folk traditions. He was an avid supporter of reviving the Irish language and was also interested in the study of Hiberno-English, which is the dialect of English spoken in Ireland. This volume explains the phonetic laws under which Irish place names were anglicised. A large proportion of Irish place names remained Celtic in origin while only one thirteenth had been influenced by the presence of British power structures. It is interesting to note that this work was dedicated to Patrick Joseph Keenan, who became the first Catholic to hold the position of resident commissioner of national education of Ireland. Joyce’s dedication to Keenan ‘as a small tribute to genius, patriotism, and kindness of heart’ encapsulates the spirit of Irish patriotism during a time when there were major campaigns for a ‘Gaelic Revival’. The front cover of the book, the title page and both prefaces are decorated with famous iconography that is associated with Celtic Ireland. The illustrations include round towers, ogham stones, Celtic crosses and standing stones. Both prefaces include calligraphy similar to that which can be seen on the renowned Irish illuminated manuscripts such as The Book of Kells.

Library no. E.28.15

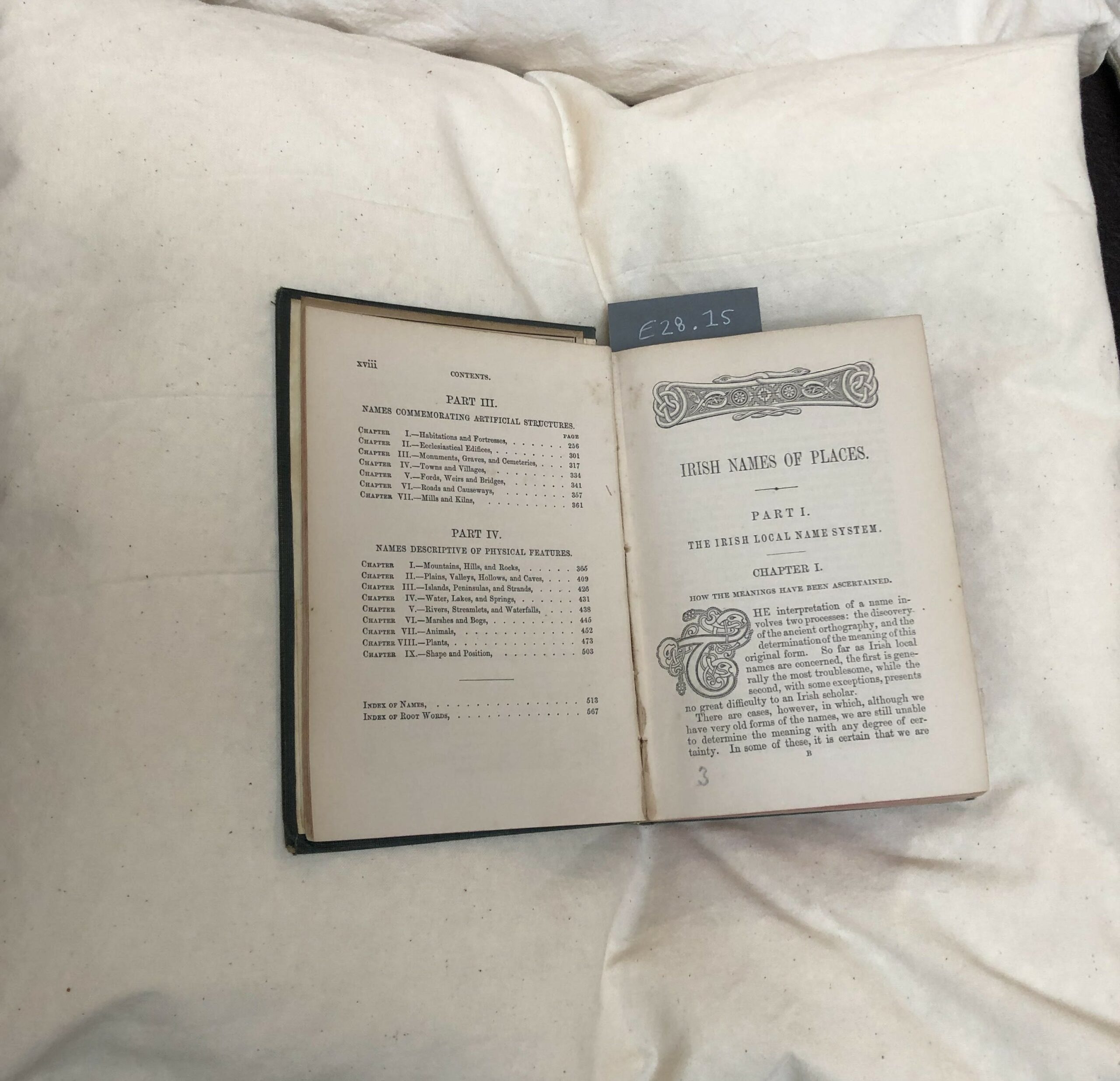

Francis Grose (1731-1791)

The Antiquities of Ireland, (1791)

Francis Grose was born in Middlesex and became a well-established antiquary, lexicographer, and draughtsman. His father bought him a place in the College of Arms, which he resigned from, and was left a substantial fortune that he is said to have wasted. In 1757 he was elected as a member of the Society of Antiquaries and resumed his career as a soldier in 1759. His classical education and gift for drawing led him to publish his first major work Views of Antiquities in England and Wales. He embarked on an expedition to Ireland to write this work but soon after had an apoplectic fit and died. His nephews Daniel and Dr. Edward Ledwich had luckily already worked on Irish antiquities and published the final version of Grose’s work in 1791. On 18 May 1791 he was buried in Drumcondra cemetery in Dublin where his father had built a house nearby. Art historian William Hauptman maintains that this book is still an important historical resource as it captures precisely how Irish monuments and antiquities looked at the end of the eighteenth century. The front of the book also includes some pagan antiquities, such as Newgrange, a 5000 year old passage tomb in county Meath, which is pictured here.

Library no. S 31. 11-12

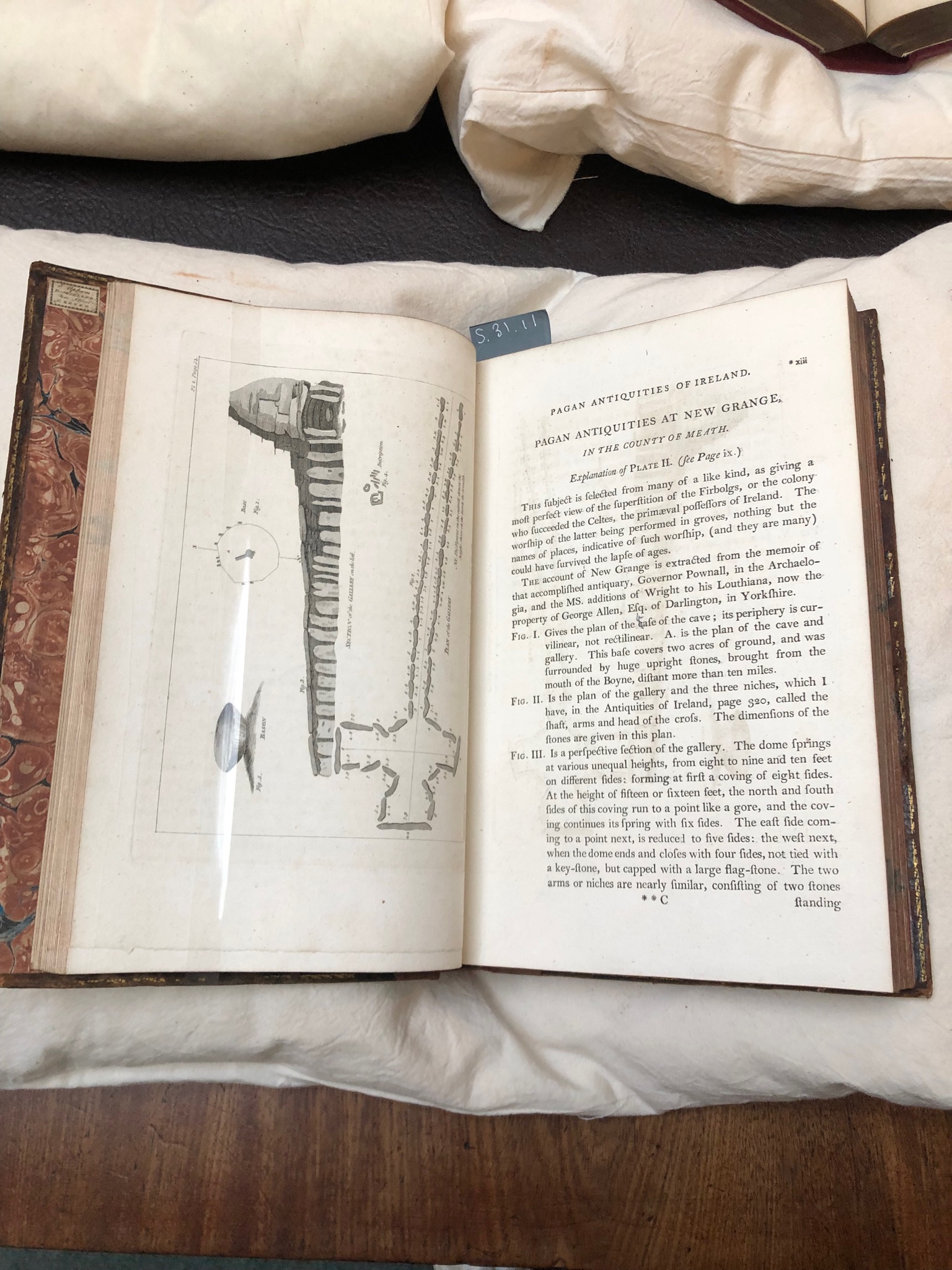

Geoffrey Keating (c1569 – 1644)

A General History of Ireland viz. A full and impartial Account of the Original of the Kingdom; with the Lives and Reigns of an Hundred and Seventy-four Succeeding monarchs of the Milesian Race. The Original of the Gadelians. Their Travels into Spain, and from thence into Ireland. Translated from Irish by Dermod O’ Connor (1738)

Keating was an Old English Catholic priest in County Tipperary. The ‘Old English’ in Ireland referred to the descendants of those who arrived during the Norman invasion and had become largely Gaelicised through culture and marriage. The ‘New English’ arrived during the Tudor and Stuart conquests of Ireland in the 16th and 17th centuries and came to be known as the Protestant ascendancy. Keating’s work highlights the ancient traditions and history of settlement in Ireland prior to the confiscation of Irish land. This was written during a time when national histories were increasingly being written as a method of affirming an Irish national identity. Historian Clare O’ Halloran asserts that Keating’s work was a response to accusations from the Protestant ascendancy that Ireland was in need of civilisation due to their alleged barbarism. This work therefore attempted to show the learned nature of the ancient Irish. The frontispiece depiction of Brian Boru, the 11th century High King of Ireland, was a popular image during this period which represented efforts to form a homogenous Catholic Irish identity amongst the indigenous Irish and the Old English.

Library no. B 26.9

Sir Thomas Stafford (c1574-1655)

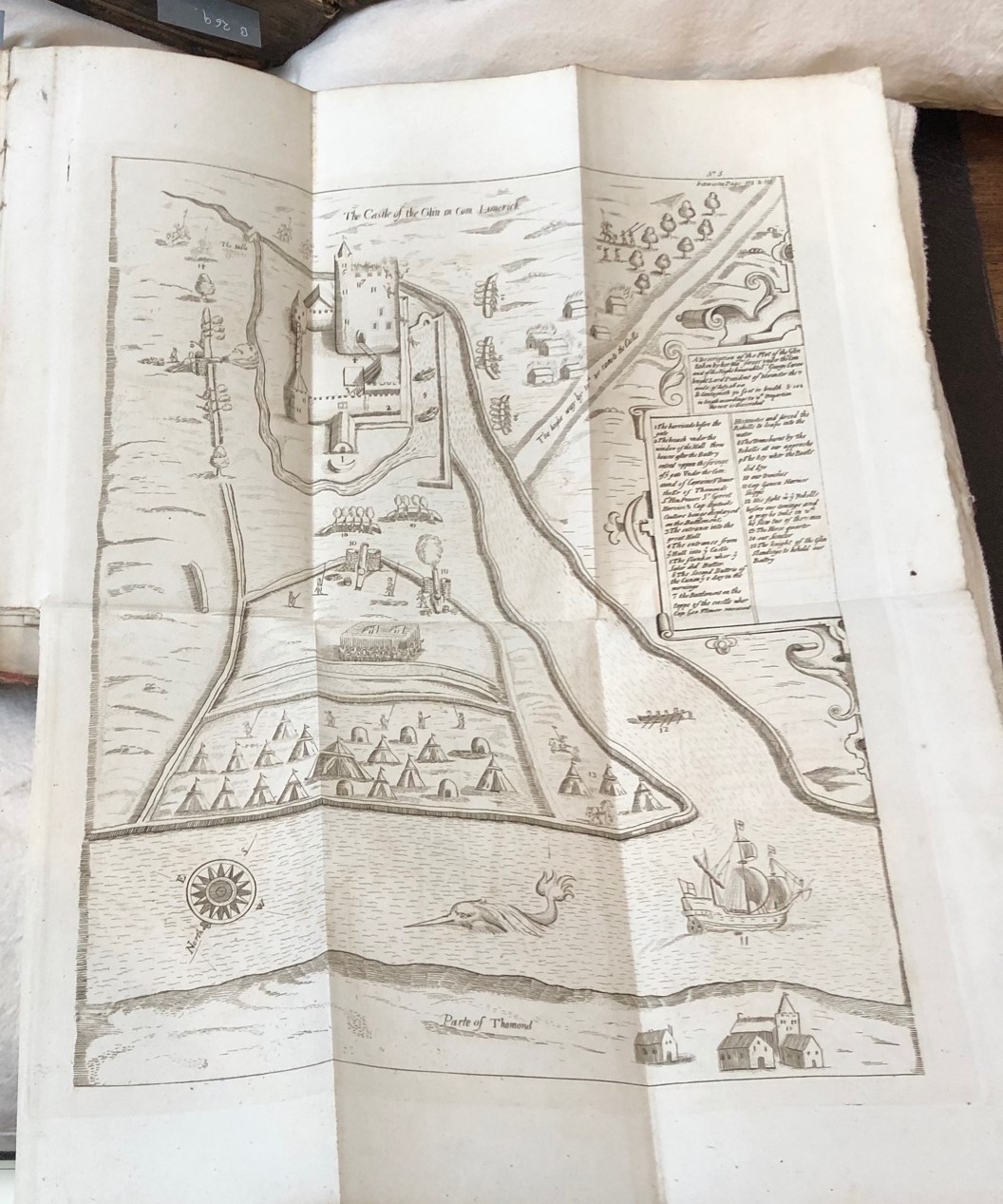

Pacata Hibernia: Ireland appeased and reduced, or, A History of the wars of Ireland in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, Reprinted for James Taylor, by S. and R. Bentley, (1821)

Stafford was an English courtier and antiquarian who was particularly interested in the Irish Wars. He is thought to be the illegitimate son of George Carew, who was the earl of Totnes and was made president of Munster during the reign of Elizabeth I. Stafford inherited some of the manuscripts that Carew had compiled relating to Ireland, which he used to inform this text. Pacata Hibernia was promoted as an impartial historical account of the end of The Nine Years War, with particular reference to the province of Munster. This war was led by Hugh O’ Neill of Tyrone and Hugh Roe O’ Donnell of Tyrconnell and was a response to the ongoing Tudor conquests and English rule in Ireland. The back of this volume contains engraved representations of the battles and fortifications from the war.

Library no. C 24.16-17

Reverend Robert Lampen (c1790-1849)

The Christian duty of relieving the distresses in Ireland. A sermon preached in St. Andrews’s Church, Plymouth, on Sunday, July 7th, (1822).

Reverend Robert Lampen was the Vicar of Probus in the County of Cornwall and a Prebendary of the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter in Exeter. This sermon was preached in Plymouth during the Irish crop failures of 1822. It is estimated that one million Irish people were starving at this point. Lampen proclaims, “it would be folly to suggest immediate work for those suffering as they are much too weak” and describes how people were travelling up to fifteen miles to get just “one quart of oats” to feed entire families. This crop failure proved to be a grim precursor to the Great Famine of 1845, which caused widespread devastation and halved the population of Ireland due to emigration and death from starvation. It is interesting to note the Reverend’s assertion that it would be unreasonable for Irish people to be expected to work in their condition, when considering that the Poor Laws from 20 years later imposed hard labour on the starving Irish in exchange for food.

Library no. TRACTS 106/1

—by Amber Flood, PhD researcher at the Devon & Exeter Institution.