A Seasonal Story: Charles Dickens’ Christmas Books

Many of us are familiar with Charles Dickens chilling festive tale, A Christmas Carol. Since its publication in 1843, it has been released in numerous editions and been adapted many times for the stage and screen. However, Dickens’ longstanding personal investment in the Christmas story tradition is perhaps a less-well known tale.

It has long been a tradition to tell ghost stories at Christmas time, but in the 19th century, Christmas ghost stories were written, published, and disseminated with a whole new energy. The steam-powered printing press and the invention of wood-pulp paper revolutionised the print industry, allowing for greater and more-rapid dissemination of printed material. As a popular novelist, Charles Dickens, (1812-1870), was well-placed to capitalise on these modern developments. Between 1843 and 1848, he wrote five Christmas novellas, starting with the Carol, which was conceived of and written in just six weeks in late 1843. After the strange tale received such a welcome from its hungry public, Dickens set about creating a seasonal story for each consecutive year. His third story, The Cricket on the Hearth, (1845), was confidently released alongside seventeen stage productions. Unfortunately, his 1846 creation, The Battle of Life, never met the success of his previous tales, and received negative reviews in the press. The Morning Chronicle particularly condemned a story “so bald and […] so absurd.” It was with some apprehension, then, that after a year’s break, Dickens once again began to write a Christmas tale in late 1848.

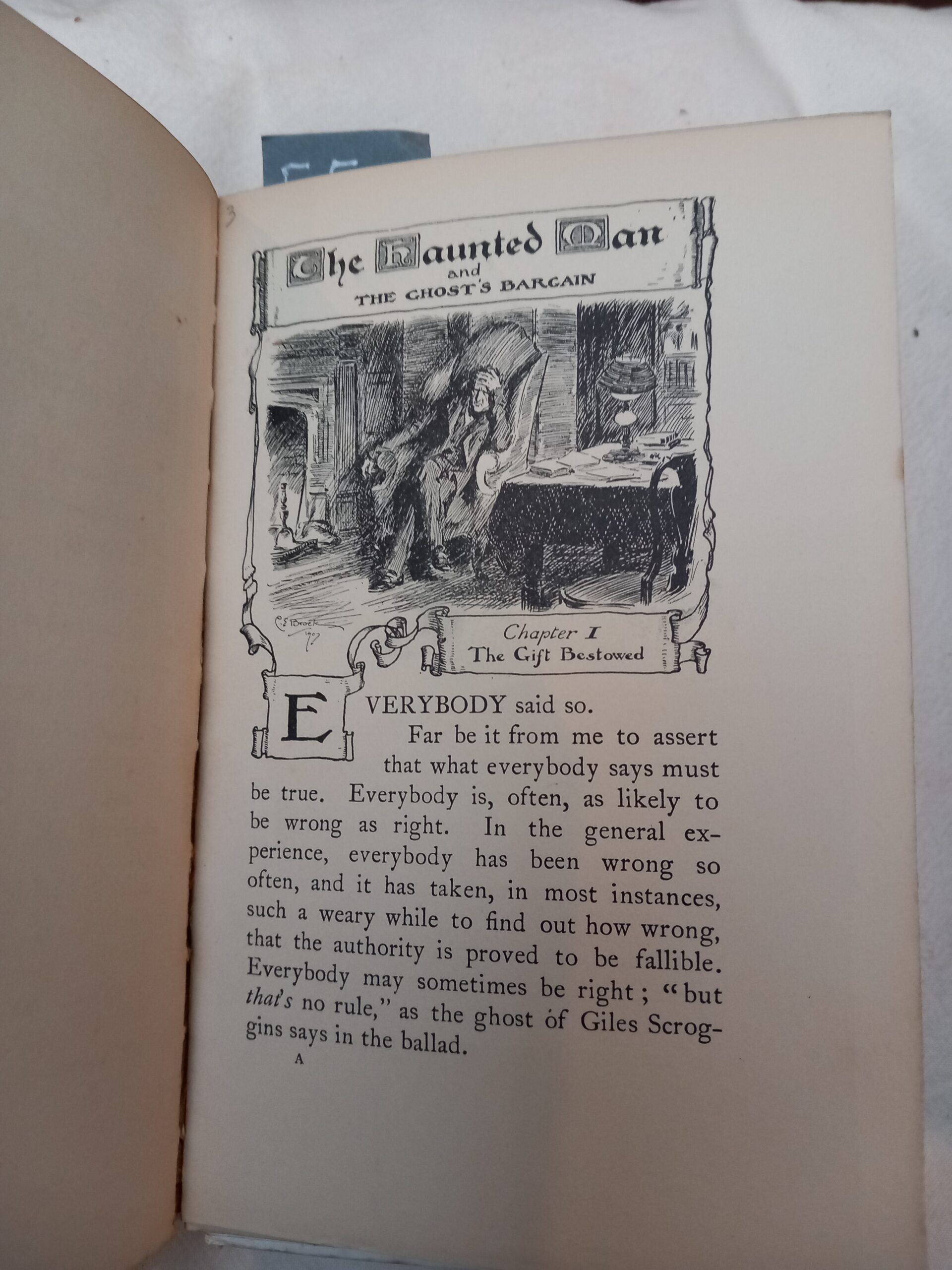

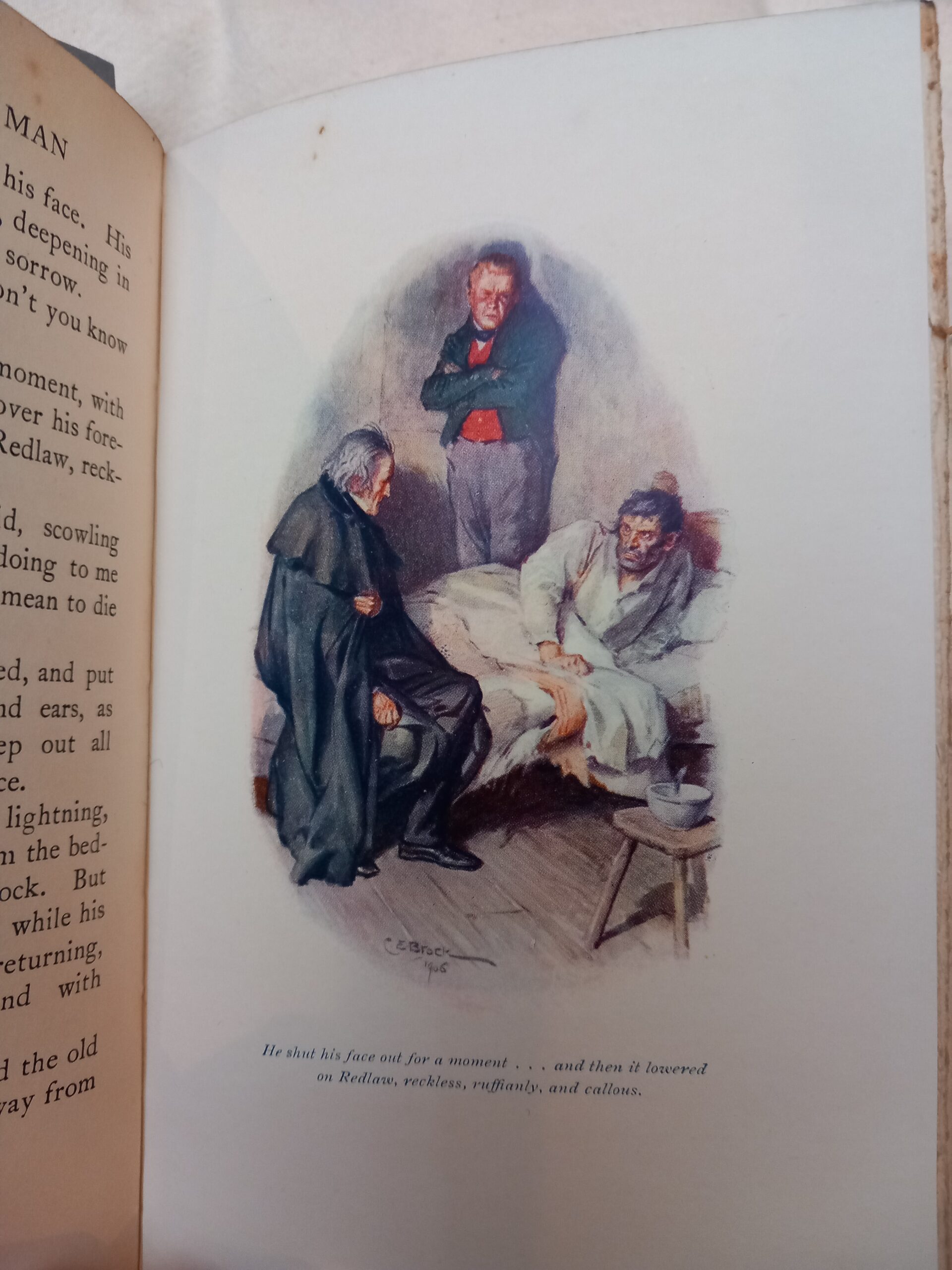

The story Dickens set about writing eventually became known as The Haunted Man, and the Ghost’s Bargain. The Devon and Exeter Institution has two copies of the tale: one is a particularly attractive 1907 edition with coloured plates by C. E. Brock, (1870-1983) , the other appears in a multi-volume series of Dickens’ works, concluding with his “Christmas Books etc.,” and “Christmas Stories.” The volume comprises a compilation of all five of Dickens’ Christmas tales, featuring some of the stories original illustrations, a collaborative effort by the celebrated Sir John Tenniel, (1820-1914), Frank Stone, (1800-1859), William Clarkson Stanfield, (1793-1867), and John Leech, (1817-1864). Clearly, by the time he came to write his later festive plots, Dickens was keen to play up the pictorial element. Originally advertised as a volume “elegantly bound in cloth,” Dickens’ fifth Christmas volume was a canny attempt to tap into the increasingly commercial aspect of the season, and to appeal to the festive shopper in search of a suitable gift. The subsequent release of his Christmas tales in a collected edition invited the Victorian reader to invest in the festive compilation, and to re-read them in Christmases to come.

Despite its decorative clothing, The Haunted Man was a classic contemporary ghost tale, tapping into the nineteenth-century zeitgeist. The plot appealed to Victorian sentimentality, and reflected Dickens’ personal preoccupation with conditions for orphans and the working-class in Industrial London. Redlaw, a disaffected Chemistry teacher, is visited by a ghost, and receives a unique but troublesome gift to wipe the memories of every individual he encounters. From the moment this power is bestowed upon him, he is haunted by the spirit of a homeless child, who accompanies him on various visits to other individuals. First, he visits the Tetterbys, and causes their boarder, Mr Denham, to forget the efforts of the woman who has nursed him in a time of ill health. Afterwards, he calls on the Swidgers, and the older man fails to recognise his son. Following these experiences, Redlaw begins to doubt the merits of forgetfulness. Later, it is revealed to Redlaw that the child’s state is the consequence of fugue: without the remembrance of the sorrows that shape him, Redlaw risks becoming benumbed and irredeemable. The story concludes with a characteristic moral:

“Christmas is a time in which, of all times in the year, the memory of every remediable sorrow, wrong, and trouble in the world around us, should be active with us.”

Though nowadays we might associate such gothic stories as synonymous with Halloween, Christmas for the Victorians was a time of reflection and anticipation. Families could gather round the fireplace to read a terrifying tale together. It was a tradition that Dickens cemented by publishing such stories in a tantalising volume. Later, he would abandon full-scale novellas, and instead create shorter Christmas stories for publication in his popular periodical Household Words. Through his efforts, Dickens truly created a market for seasonal reading, a legacy that has rippled into the contemporary tendency to buy our nearest and dearest a book for Christmas.