An Invitation to Create #14- Whale Compass

The eternal whale will still survive, and […] spout his frothed defiance to the skies.”- Herman Melville, Moby Dick (1851).

What would a whale say on social media? A study emerged this week suggesting that sperm whales, which possess the largest brains on the planet, have developed a means of warning each other of threats. Though sperm whales have long adopted a means of collaborative defence in response to their only natural predators, orcas, it seems their patterns of communication altered significantly during the rise of commercial whaling in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the time of the industrial revolution, numerous whaling ships relentlessly hunted the whales for their meat and blubber, which would later be converted into oil for lamps, soaps, and other uses. In response, the whales dispersed, and passed information to each other about the locations of the vessels through echolocation. In just a few years, the whalers’ strike rate in the North Pacific fell almost by half.

What would a whale say on social media? A study emerged this week suggesting that sperm whales, which possess the largest brains on the planet, have developed a means of warning each other of threats. Though sperm whales have long adopted a means of collaborative defence in response to their only natural predators, orcas, it seems their patterns of communication altered significantly during the rise of commercial whaling in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the time of the industrial revolution, numerous whaling ships relentlessly hunted the whales for their meat and blubber, which would later be converted into oil for lamps, soaps, and other uses. In response, the whales dispersed, and passed information to each other about the locations of the vessels through echolocation. In just a few years, the whalers’ strike rate in the North Pacific fell almost by half.

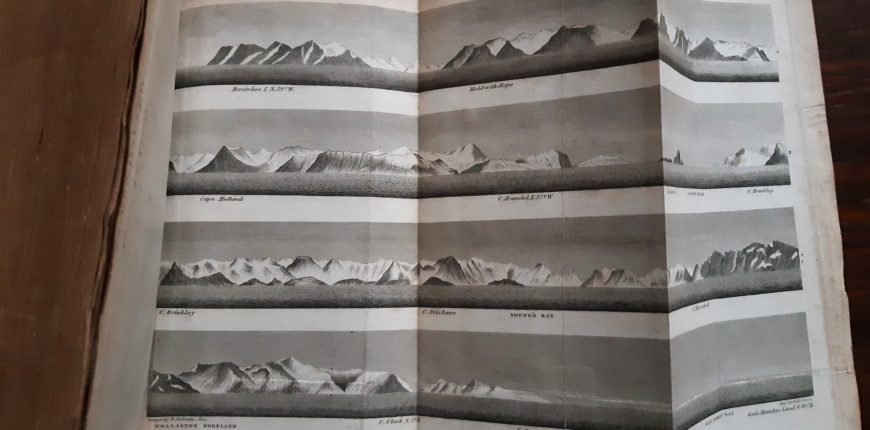

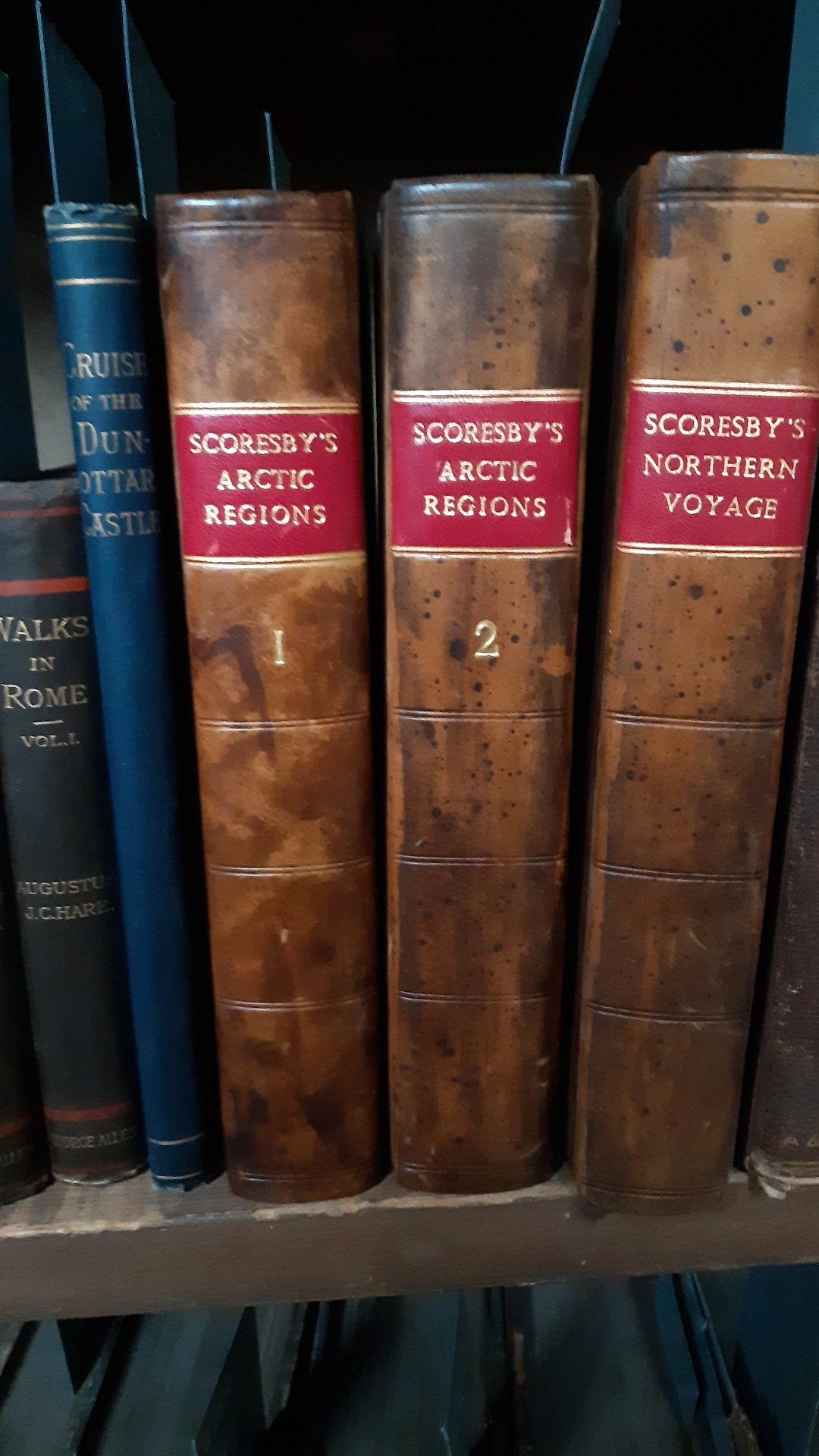

Amongst the DEI Collections we have a fascinating volume entitled Journal of a voyage to the northern whale-fishery: including researches and discoveries on the eastern coast of West Greenland, made in the summer of 1822, in the ship Baffin of Liverpool (1823). This journal was kept by William Scoresby junior, a whaler, explorer, and scientist who eventually settled in Torquay, Devon. Whilst the scale and persistence of these whale hunting expeditions might seem unsettling to us today, this book, with its beautifully-illustrated plates and maps, provides an important account of an industry that relied upon epic voyages to places like Greenland and Spitzbergen- no mean feat in the 1800s! As a young man, Scoresby went whaling in the breaks from his studies of natural philosophy and chemistry at Edinburgh University, and in this later volume it is notable that he also provides wider observations on the environment of the places he journeyed to. The account includes detailed descriptions of wildlife and even the geological compositions of the areas he encountered on his voyages.

Whalers also regularly engaged in a practice known as “scrimshawing,” carving detailed etchings onto whalebone and whale teeth. Though there are now understandably restrictions around dealing in or making scrimshawed works, and whaling itself is subject to environmental restrictions and regulations, these 19th century pieces afford us an insight into how humans affected and impacted upon this remote landscape and its wildlife, and encourage us to reflect on our evolving relationship with the natural world. If pioneering shipping and mapping technologies enabled large-scale travel to arctic regions in the 19th century, we are, as this week’s revelation proves, still making new discoveries. The question is, how do we use this information, and in what direction do we take it?

In later life, William Scoresby devoted increasing amounts of his time to the study of magnetism, in order to improve the accuracy of the ship’s compass. This week, we are inviting you to make your own compass, inspired by his work!

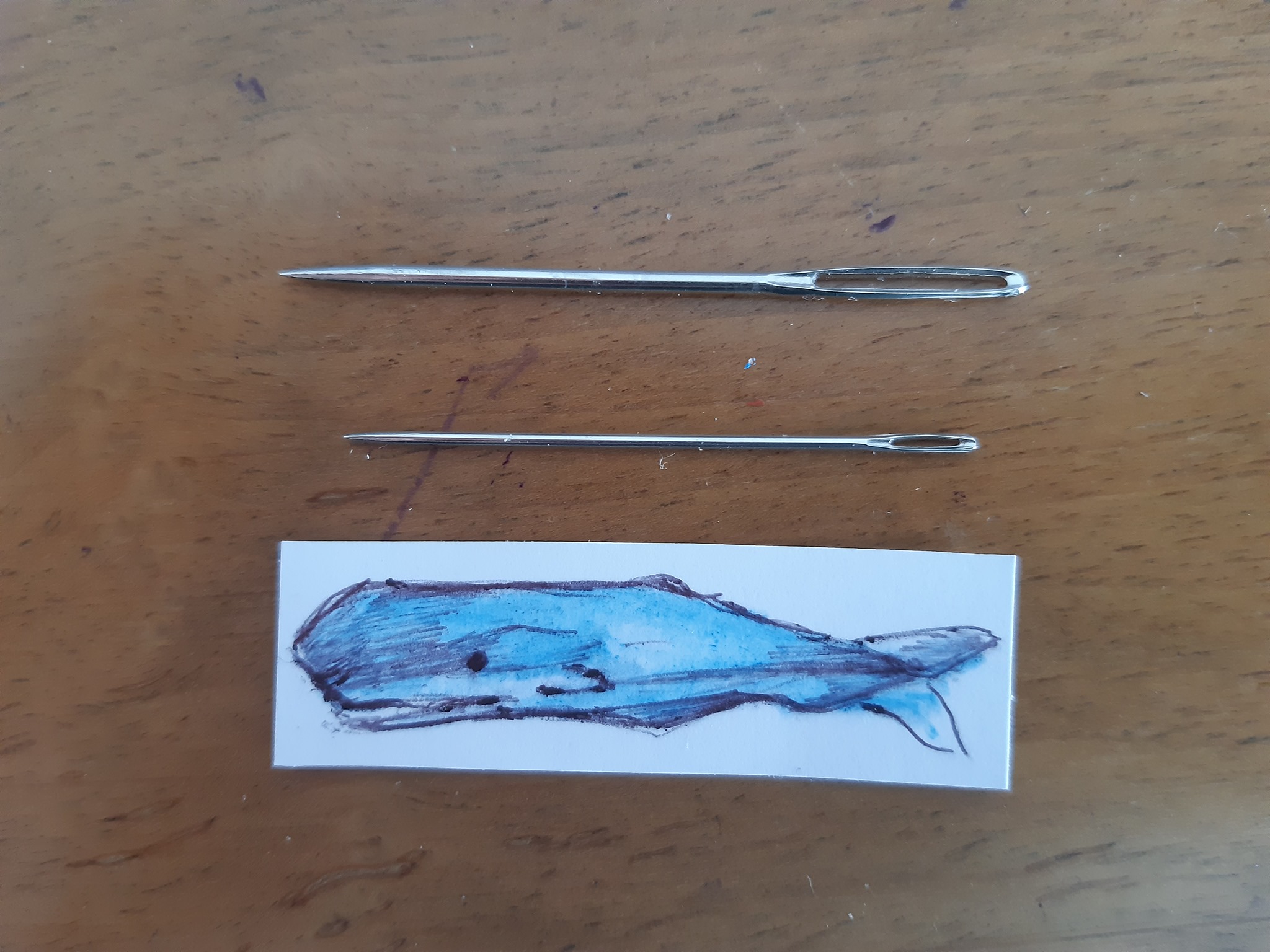

When we record something, we look at it in a new way. Drawing or depicting something encourages us to develop a different relationship with it. First, we would like you to depict a whale, in ink, in collage, in paint, or in pencil. Make sure your whale is roughly the size of needle (choose a darning needle if this is easier!) Attach this drawing to a cork with clear tape. Place your whale-decorated cork in a bowl of water on a flat surface. Let the needle calibrate itself, and eventually, its point should point north!

Bethany Howell

Saturday Activities Coordinator