Women’s Travelogues: Isabella Bird

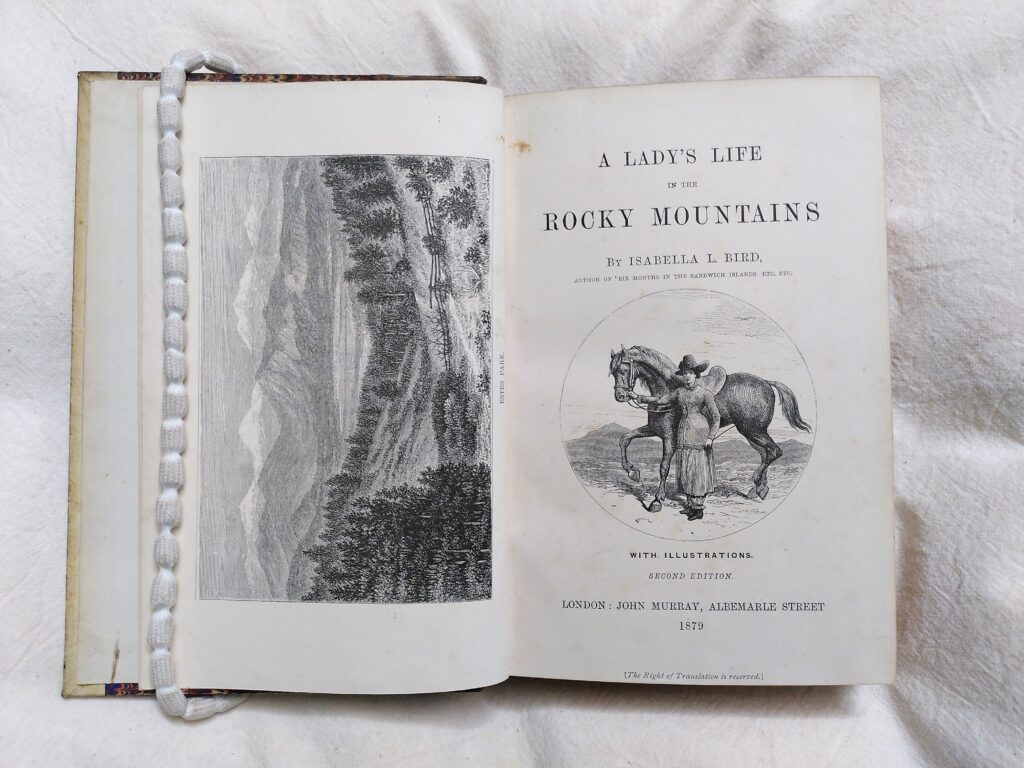

In the final instalment of her special edition Book of the Month blog, Isabel Moon discusses Isabella Bird’s ‘A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains’ (1879). A prolific writer and explorer, Bird was the first woman to be allowed to join the Royal Geographical Society. Her account of travelling in nineteenth-century Colorado is unique in giving a woman’s experience of the male-dominated world of the Western frontier. History MA student Isabel has just completed a project which explores the works of the 19th-century women who feature in our Voyages and Travels collection, and asks how we should engage with this material as a 21st-century audience.

Isabella Bird

A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains (1879)

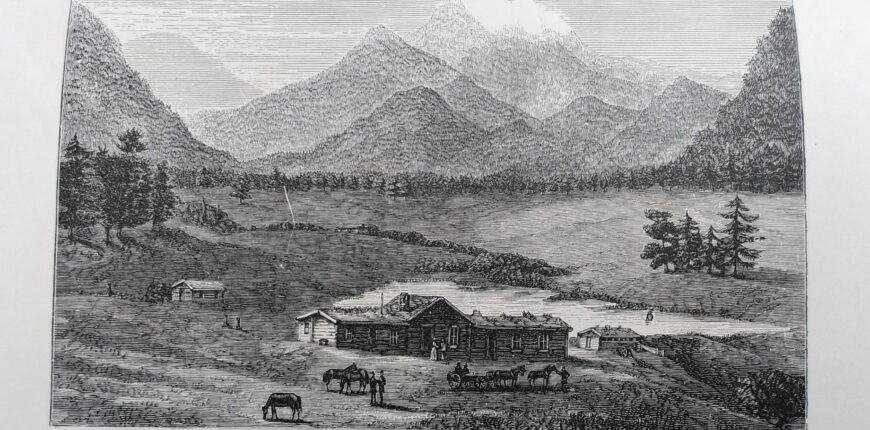

Isabella Bird was an explorer, writer, photographer, and naturalist born in Yorkshire in 1831. Based on the letters sent to her sister during her travels, this book tells the story of Bird’s three-month journey through the 19th-century Rocky Mountains in Colorado. What makes Bird’s narrative unusual is that she travels mostly alone, which highlights the isolated and male-dominated nature of the territories she travels through. A passage describing her accommodation illustrates her having to establish herself in the spaces habitually occupied by men. As the 19th century progressed, it became increasingly possible for women to travel independently beyond typical tourist circuits. As a result, more and more figures like Bird built successful careers recounting their time with people and places still little-known to those back home.

“The accommodation is too limited for the population … and beds are occupied continuously, though by different occupants, throughout the greater part of the twenty-four hours. Consequently I found the bed and room allotted to me quite tumbled-looking. Men’s coats and sticks were hanging up, miry boots were littered about, and a rifle was in one corner.”

Most historians agree that Bird’s construction of gender and her position as a woman traveller is a crucial feature of this story. Whether in the descriptions of her daring and dangerous adventures or her experience as a woman alone in an incredibly masculine environment, this element of Bird’s story is vital to the book.

Often the focus by those studying this book is on her time spent with the notorious Rocky Mountain Jim, an infamous local mountain ranger who Bird conflictedly depicts as charming and dangerous, regularly reminding the audience of his reputation, crimes, and eventual death after the events of her story. The characterization of Rocky Mountain Jim echoes romantic novels :

“His face was remarkable. He is a man about forty-five, and must have been strikingly handsome. He has large grey-blue eyes, deeply set, with well-marked eyebrows, a handsome aquiline nose, and a very handsome mouth[…] One eye was entirely gone, and the loss made one side of the face repulsive, while the other might have been modelled in marble. ” Desperado ” was written in large letters all over him. I almost repented of having sought his acquaintance[…] We entered into conversation, and as he spoke I forgot both his reputation and appearance, for his manner was that of a chivalrous gentleman, his accent refined, and his language easy and elegant[…] So far as I have at present heard, he is a man for whom there is now no room, for the time for blows and blood in this part of Colorado is past, and the fame of many daring exploits is sullied by crimes which are not easily forgiven here[…] Of his genius and chivalry to women there does not appear to be any doubt; but he is a desperate character, and is subject to “ugly fits,’ when people think it best to avoid him[…] His besetting sin is indicated in the verdict pronounced on him by my host: ‘When he’s sober Jim’s a perfect gentleman; but when he’s had liquor he’s the most awful ruffian in Colorado.’”

Christine DeVine argues that Bird’s story has been heavily edited, and the narrative constructed into a romantic tale full of allegories and metaphors. Bird would have been very aware of the threat of speculation about her sexual and romantic deeds from audiences back home. For example, we know that she left some details out of her book that she had included in her original letters to her sister and that researchers since have discredited Bird’s stories of Jim. On the other hand, Deanna Stover interprets their romance, and the book as a whole, through its religious and imperialist overtones. In this light, Jim’s character becomes a “religious philanthropic project with just enough hint of romance to garner reader interest.”

Bird’s journey through the Rocky Mountains sees her overcome both the landscape and the people, declaring at the end that “Estes Park is mine” and presenting her adventures as both a victory for England and for Protestant ideals. As with many travel texts from the 19th century, Bird’s book combines tropes and conventions typical of fiction and allegorical books of her time that add a complicating layer to anyone reading it today as a simple travel narrative.

Conclusion

19th-century travel literature raises important questions about how modern audiences and historical institutions should engage with material containing difficult and contentious ideas and opinions. Any work with historical material must respectfully do justice to the material and its audience at the same time. This is especially true of difficult material like 19th-century travelogues and, in the course of these blog posts, I have looked at a range of ways to achieve this. Firstly, adding context to the books brings us closer to appreciating them as their original audience would have. It bridges the gap between our modern understanding and the understanding that the original 19th-century audience would have had. Secondly, including multiple viewpoints and opinions about the texts gives the audience the space to interpret the material themselves in an informed manner. Finally, in my display on Amelia Blandford Edward’s book A Thousand Miles Up the Nile, I tried to create a dialogue between the material and the audience, asking visitors how they think the DEI should curate and display works like it.

One of the things that makes these texts interesting as historical material is that they give a first-person account of the past and an insight into the writers themselves. This can allow us to better understand historical figures, their ideas and perspectives, and the period in which they lived, which is especially useful when we want to consider their achievements, and criticise their actions and beliefs. This is something that made this project particularly interesting to me and drew me to the collection itself.

The women writers I have looked at contributed greatly to their fields – as antiquaries, Egyptologists, explorers, naturalists, and more. They make great sources of information for an important moment in history. For this reason, it would be a shame and a mistake to ignore their works. We can see that many female writers wrote travel literature for similar reasons to their male counterparts; as scholarly work, for political reasons, or as an income. As such, we see similar topics explored in women’s texts, as well as some subjects which were unavailable to male writers. Unfortunately, this means the texts are also likely to include the racist and otherwise difficult content that is commonly seen in the genre and time, and that inherently goes hand in hand with Victorian discussions of “otherness.” I would argue that, in exemplifying the Victorian distrust of, and anxiety about, the racial Other, they can help us to better understand it, where it came from, and how it influenced both their world and eventually our modern world.

I would like to thank the DEI for the amazing opportunity to work with their collection as part of this research project. I want to send a big thank you to Emma Dunn for organising this opportunity and a massive thank you to Fiona Schroeder for her help editing and giving feedback on my work.