Women’s Travelogues: Harriet Martineau and Alison Carmichael

History MA student Isabel Moon has been exploring the works of the 19th-century women who feature in our Voyages and Travels collection. This is as part of an ongoing project which asks how we should use this material as a 21st-century audience. Following last month’s post on Elizabeth Caroline Johnstone Gray and Amelia Blandford Edwards, May’s blog spotlights works by Harriet Martineau and Alison Carmichael. As well as further illustrating the challenges faced by Victorian women working in the travel genre, these books raise important questions about how we should engage with texts that contain problematic depictions and views. Both writers engage with contemporary debates about slavery (Martineau as an abolitionist, and Carmichael as the wife of a plantation owner), and their depictions of non-white, non-European peoples reflect, to different extents, the racist prejudices prevalent at the time.

Harriet Martineau

Eastern Life, Present and Past (1848)

Harriet Martineau was a social theorist, novelist, and journalist born in 1802 into a wealthy merchant family in Norwich. She was a passionate abolitionist and produced many works on slavery in the English and French Caribbean and in North America that were highly influential in the period directly leading up to emancipation in these colonies. Her anti-slavery writing circulated in American editions leading up to and throughout the American Civil War.

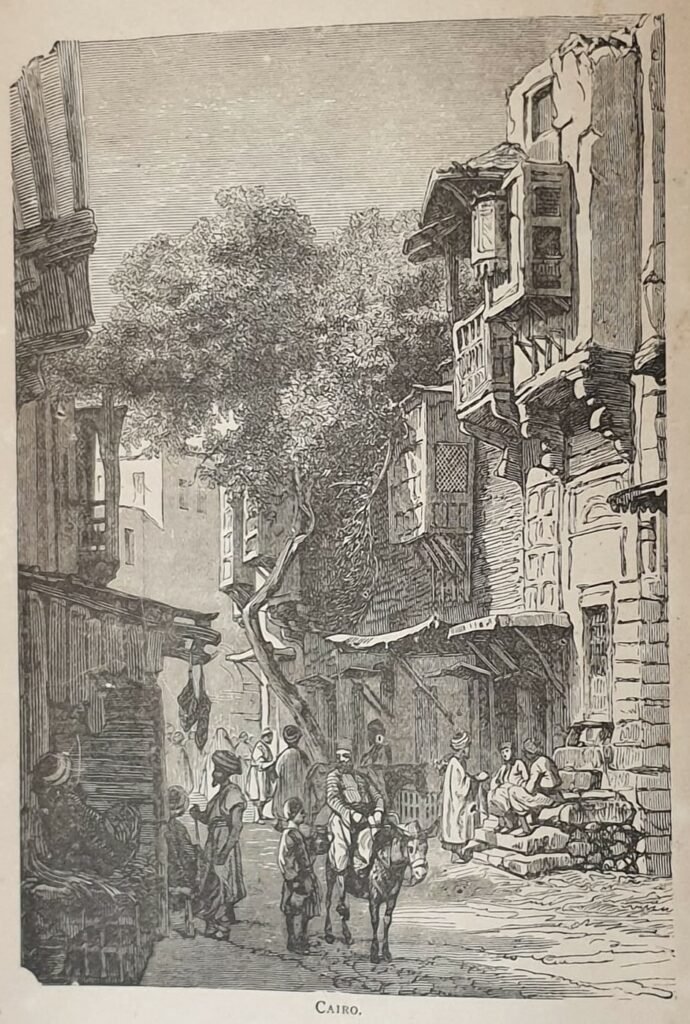

Eastern Life tells the story of Martineau’s journey through Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. This book gives the reader the impression of looking through her eyes at the world around her. It is mostly a study of the religious history and practices of the countries Martineau visits, but it is also filled with her political and moral judgments of what she sees.

It was not until the 19th-century that a significant number of travelogues by women began to be published. Despite the judgements of chauvinistic reviewers, many, like Martineau, were drawn to the genre because of its intellectual prestige and the opportunity to discuss political and sociological themes.

“Most of the girls were grinding millet between two stones, or kneading and baking cakes. They were freshly oiled, in good plight, and very intelligent-looking, for the most part. Some of them were really pretty in their way, in the old Egyptian way. They appeared cheerful, and at home in their business; and there can scarcely be a stronger contrast than between this slave-market and those I had seen in the United States.”

For modern readers, Martineau’s objective tone may seem jarring when she describes certain topics, for example, a slave bazaar in Aswan. She writes a very matter-of-fact description of the young girls offered for sale and finishes the passages explaining how slavery was “infinitely less repulsive in Egypt than in America”, though the institution as a whole was ultimately “no more defensible [in Egypt] than elsewhere.” Martineau’s tone may have helped her be taken more seriously as a female writer. By appearing rational, serious, and detached, she forestalled contemporary critics who might object that a natural delicacy must “preclude a female from doing literary justice to a tour”. But this approach might prompt criticism from 21st-century readers who may feel she doesn’t do justice to what she is describing here.

For modern readers, Martineau’s objective tone may seem jarring when she describes certain topics, for example, a slave bazaar in Aswan. She writes a very matter-of-fact description of the young girls offered for sale and finishes the passages explaining how slavery was “infinitely less repulsive in Egypt than in America”, though the institution as a whole was ultimately “no more defensible [in Egypt] than elsewhere.” Martineau’s tone may have helped her be taken more seriously as a female writer. By appearing rational, serious, and detached, she forestalled contemporary critics who might object that a natural delicacy must “preclude a female from doing literary justice to a tour”. But this approach might prompt criticism from 21st-century readers who may feel she doesn’t do justice to what she is describing here.

While Martineau may not have wished to emphasise her gender, her travelogue, in describing a woman’s experiences, provides a unique perspective for the reader. For example, we see inside some spaces that a male writer would not have been allowed to visit. The Harem was such a space, and one that had particularly “caught the imagination of the West” at this time. In contemporary art and literature, Harems were often depicted as exciting, mysterious, exotic, spaces. By contrast, Martineau adopts a realistic, rather than a romantic, tone. She emphasises how unpleasant and saddening her visit was, and vehemently condemns polygamy in the form she saw it. She describes the women as “miserable-looking”, calls them “dull, soulless, brutish, or peevish,” and generally stresses their unhappiness and boredom. Shirley Foster explains that such responses were typical of Western women, who often expressed sympathy for women living within a system which they felt must “enslav[e] their bodies and coloniz[e] their minds.” Whatever her intentions, Martineau creates a portrayal of the women in the Harem that at first appears shocking, but counters the Romantic, Orientalist depictions of these spaces created by some men at the time.

“The moonlit plain lay, with the river in its midst, within the girdle of mountains. Here was enthroned the human intellect when humanity was elsewhere scarcely emerging from chaos. And how was it now? That morning, I had seen the Governor of Thebes, crouching on his haunches on the filthy shore among the dung heaps, feeding himself with his fingers, among a circle of apish creatures like himself”

Historian Cora Kaplan asks an interesting question: how should 21st-century readers approach the contradictions between Martineau’s strong abolitionist sentiments and the “disturbing racial tropes that erupt from her observations of actual slaves?” Similarly, John Barrell highlights the ape-like imagery Martineau uses to describe the Governor of Thebes, which evokes contemporary discussions about anatomical similarities and differences between human beings and apes – precursors of Darwin’s evolutionary theory. Like many Victorian Egyptologists, Martineau, despite some of her otherwise progressive ideas, celebrated and idolised the ancient Egyptian world but had little to no respect for the contemporary population.

Alison Carmichael

Domestic Manners and Social Condition of the White, Coloured, and Negro Population of the West Indies (1834)

Alison Carmichael was most likely an educated, Scottish gentlewoman who wrote to defend the plantation-owning class against abolitionists. In contrast to Martineau, Carmichael believed that the conduct of plantation owners and managers in the West Indies was just and humane, and that the non-white population had lower morals and intelligence. In her book, she describes living in the West Indies after she married her husband and moved to his plantation.

Although Carmichael does not take us on a journey but rather builds a stationary picture of her experience living abroad, this style is reminiscent of many female travel writers in the 18th- and 19th-centuries who experienced other countries while accompanying their husbands and families. Carmicheal clearly states that her objective is to combat what she sees as the false characterisation of the treatment of enslaved peoples in the West Indian Colonies made by abolitionists and politicians at the time. Although Carmicheal tells the reader that her book was not made for any particular occasion, her preface references “the agitation of the West India question by the present government.” This is likely a response to the Slavery Abolition Act that received royal assent in 1833, the year before Carmichael’s book was published, and would go on to abolish slavery in most British Colonies.

Carmichael uses her position inside the West Indies to legitimise her views on slave ownership. This was a common tactic for both sides of the abolition debate. Like other books, Carmichael claims objectivity: “I can only record facts” and “not the conclusions to which they lead.” Like other 19th-century female travel writers, she underplays her own expertise, promising picturesque or “objective” descriptions rather than her own informed insights or opinions. This approach allowed many to talk about matters not considered appropriate for their gender, such as politics, without reproach. Secondly, as Angela Perez-Mejia argues “if these women suffered discrimination in their travels for the fact of being women… their European origins and their white skins allowed them to assume a position of superiority as narrators with respect toward any other race.” While Carmichael may have had to battle with preconceptions about her ability to engage with the intellectual discussions surrounding abolition as a woman, she was white, wealthy, and married into the plantation-owning class, and this afforded her the opportunity to participate in the debate by means of this book.

It is a difficult read, not just because of the language used, as we can see in the title, but the casual way Carmichael talks about what she sees. The way she moves between descriptions of remarkable cruelty to delightful scenery is unsettling. While she occasionally recognises some of the brutal treatment the enslaved people around her undergo, she ultimately sympathises with the “owners”, and believes it her “duty to defend a class which has been aspersed, and to which [she herself] belonged .”

Books like this raise difficult questions about how libraries should treat texts and objects associated with imperial violence and oppression. Should it be displayed? And if so, how? Is there value in engaging the public in the uncomfortable aspects of the past? Does a text like this spoil our journey through the works of 19th-century female travel writers or does it deepen our understanding when we have a fuller and more varied picture of Britain’s history?