Sir George Staunton (1737-1801)

An authentic account of an embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China (London, 1798)

Staunton was born in Galway in 1737, and studied medicine at the University of Montpellier. He practised as a physician in the West Indies and bought an estate in Grenada where he was appointed attorney-general. He became very friendly with George McCartney (1737-1806), the governor of the islands; when Staunton’s plantations were pillaged following the French fleet’s attack in 1779, McCartney, who had been appointed governor of Madras, offered Staunton the post of private secretary. Staunton performed several diplomatic missions in India and returned to England in 1784.

Staunton was born in Galway in 1737, and studied medicine at the University of Montpellier. He practised as a physician in the West Indies and bought an estate in Grenada where he was appointed attorney-general. He became very friendly with George McCartney (1737-1806), the governor of the islands; when Staunton’s plantations were pillaged following the French fleet’s attack in 1779, McCartney, who had been appointed governor of Madras, offered Staunton the post of private secretary. Staunton performed several diplomatic missions in India and returned to England in 1784.

In 1792 Staunton was appointed principal secretary to McCartney’s embassy to China. The embassy sought to improve commercial relations with China and to establish ‘an amicable and frequent intercourse … for the mutual convenience of both nations’. Despite motivated by a ‘strong incentive of curiosity’ and an eager ‘spirit of enquiry’, the embassy was unsuccessful: McCartney and Staunton gained an audience with the emperor of China but their proposals were rebuffed.

Though politically unsuccessful, the embassy led to increased knowledge of China within Europe. Staunton closely observed and noted all that he saw and collected botanical specimens.

The sea was perfectly smooth; and its surface studded with innumerable clusters of coral islands. The substance of which they are composed is in a hard state, and similar to rock; but in various places considerable quantities of zoophytes were dragged from the sea, some of a fleshy, and some of a leathery texture. Of the corals there were vast masses, and of various species, the madrepora, cellipora, and tubipora, of different shapes, flat, round, and branched; and, as to colour, brown, white, and blue; and all these colours not unfrequently in the same specimen; but none red, except the tubularia musica.

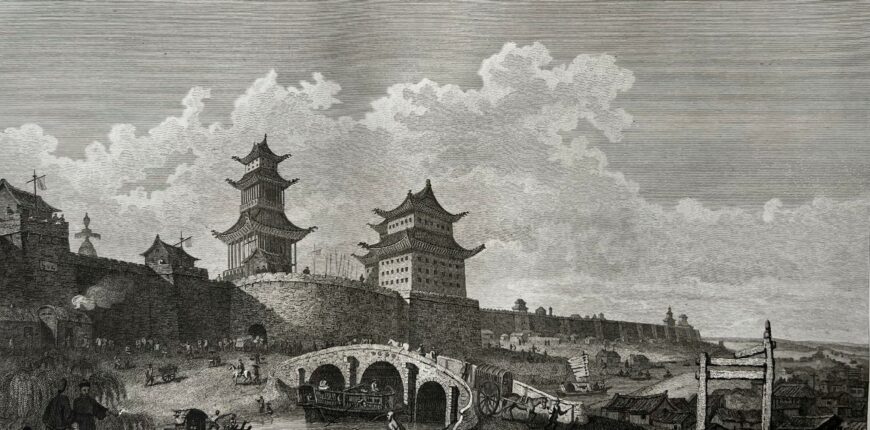

Before his death in 1801, Staunton published the official account of the embassy to China, incorporating descriptions and accounts from the papers of McCartney and of Erasmus Gower (1742-1814), the Commander of the expedition. Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820), President of the Royal Society of Arts, selected and arranged the remarkable engravings.

Staunton’s account is richly detailed and very informative of Chinese society. It offers extraordinary insights into the beginning of British imperialism in China, and is an important primary source of the history of Sino-Western relations. It also represents a historic failed opportunity to establish good relations, and led directly to the British occupation of Hong Kong. The descriptions of the countries visited during the voyage to and from China are also valuable.

The two volumes are accompanied by an atlas which contains numerous copper-plate etchings and a folded chart of the track followed by the two ships, Hindostan and HMS Lion, around the world. The draughtsman, William Alexander (1767-1816), travelled with the embassy and made numerous sketches and colour wash drawings, including views of palaces, temples, sailing vessels and military forts. The plates were issued in parts, each costing 7s 6d and containing a portrait, a subject of civil, military, or sacred architecture, a group of figures illustrating some particular employment or ceremony of the different ranks of society, and an exact representation of the various ships and vessels used in China.