Samuel Parkes (1761-1825)

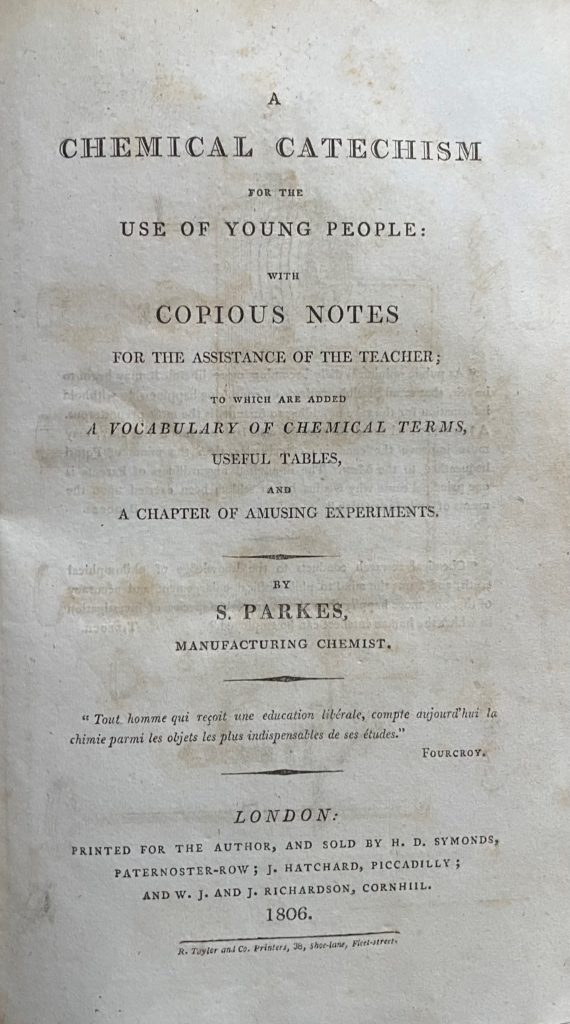

A chemical catechism (1806)

Samuel Parkes was self-taught. He began his career in his father’s grocery business in Stourbridge and in 1793 moved to Stoke-on-Trent to work as a soap manufacturer. Keen to improve his product, Parkes began to study chemistry and apply it to his work:

Samuel Parkes was self-taught. He began his career in his father’s grocery business in Stourbridge and in 1793 moved to Stoke-on-Trent to work as a soap manufacturer. Keen to improve his product, Parkes began to study chemistry and apply it to his work:

If we look to the manufactures of the kingdom, there is scarcely one of any consequence that does not depend upon chemistry, for its establishment, its improvement, or for its successful and beneficial practice.

By 1803 he had settled in London as a manufacturing chemist.

Parkes married on 23 September 1794; his daughter, Sarah, was born three years later. When Sarah was about nine years old, Parkes produced a series of chemistry lessons for her in manuscript form. These were published in 1806 as A Chemical Catechism for the use of young people: with copious notes for the assistance of the teacher. The book went through thirteen English editions, numerous American editions and was translated into French, German, Spanish and Italian. It even reached the Emperor of Russia who, it is said, sent him a valuable ring in return. Parkes published further works, including The Rudiments of Chemistry (1809) – an abridged version of his Chemical Catechism for use in schools – and Chemical Essays (1815), a five-volume work.

Parkes advocated the study of chemistry for its ‘habit of investigation’. Chemistry, he believed, ‘lays the foundation of an ardent and inquiring mind’, whatever a child may grow up to do. He also believed in encouraging a ‘love of knowledge’; the catechetical form was not intended to be rigid or to be ‘committed to memory verbatim by the pupil’. Instead, ‘whether it be employed as a catechism, as a set of dialogues, as matter for familiar conversation, or as a book for the closet’, Parkes hoped to encourage students to undertake self-study and develop a passion for the subject.

Samuel Parkes presented his book to parents as ‘a body of incontrovertible evidence of the wisdom and beneficence of the Deity’ and made no apology for including ‘moral reflections’ that might seem ‘irrelevant to chemical science’ but which he believed might defend young readers ‘against immorality, irreligion, and scepticism’. No doubt, such remarks derived from his strong Unitarian faith, but probably also served as a clever marketing ploy. Parkes also softened the text and broadened its appeal with numerous excerpts of poetry by the likes of James Thomson, William Falconer, William Hayley, Mark Akenside and Erasmus Darwin; art, science and commerce were inextricably connected in Parkes’ enlightened view of the world.

Following the chapters on air, heat, water, earths, alkalies, acids, salts, combustibles, metals and oxides, Parkes provides ‘a chapter of amusing experiments’, describing the methods but leaving the student to ‘discover the cause of every effect …’:

‘Nothing tends to imprint chemical facts upon the mind so much as the exhibition of interesting experiments. With this view the following selection has been made, in which such experiments as may be performed with ease and safety, have uniformly been preferred….’