Robert Fortune (1813-1880)

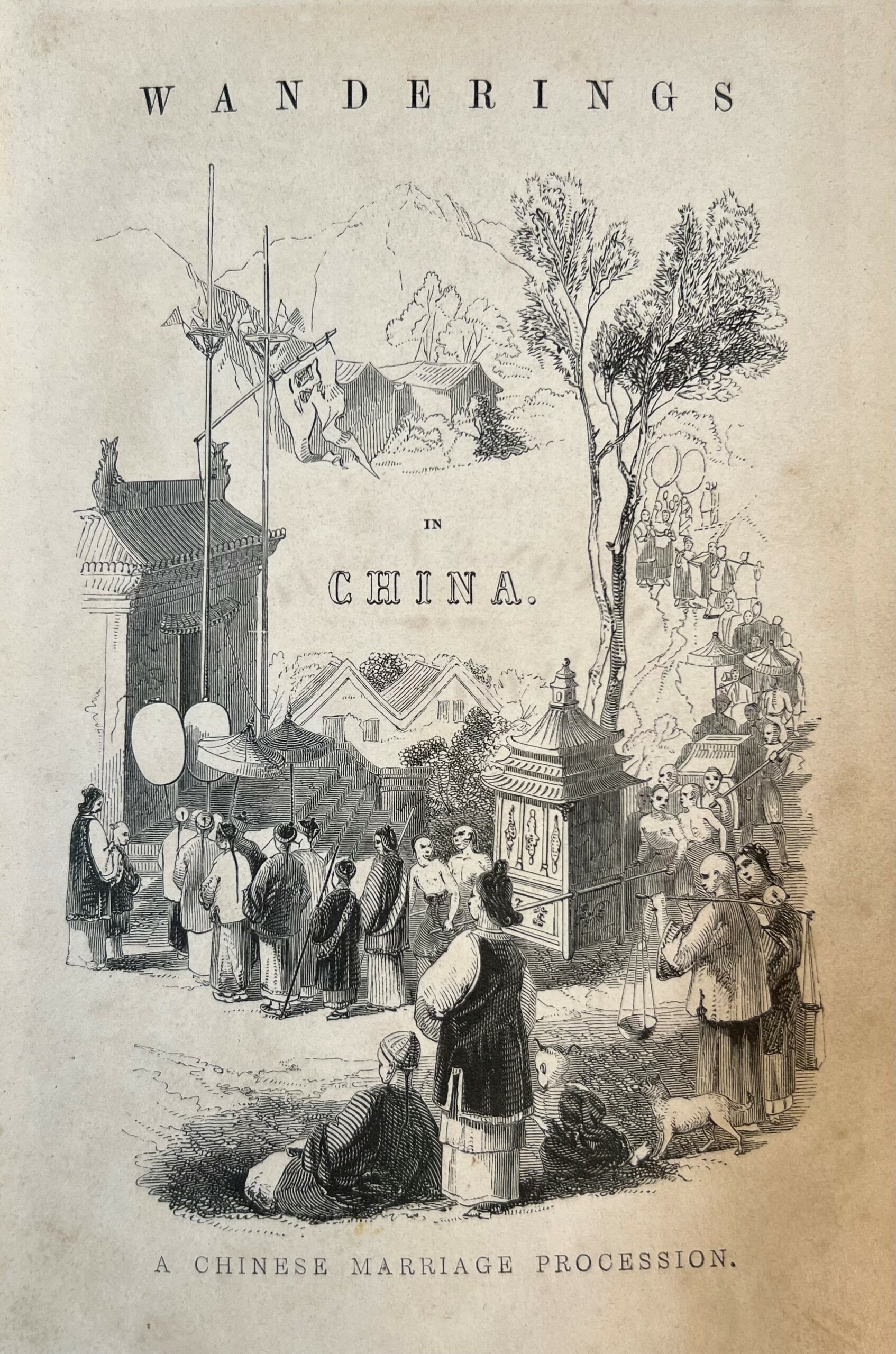

Three years’ wanderings in the northern provinces of China : including a visit to the tea, silk, and cotton countries (London, 1847)

Fortune was born in Berwickshire in Scotland. He was a skilled gardener and botanist, an entomologist and a travel writer. Though he claimed to have no intention of writing a ‘book on China’, he published a number of fascinating books full of lively incidents and perceptive accounts of inland China, then little known to Europeans.

Fortune was born in Berwickshire in Scotland. He was a skilled gardener and botanist, an entomologist and a travel writer. Though he claimed to have no intention of writing a ‘book on China’, he published a number of fascinating books full of lively incidents and perceptive accounts of inland China, then little known to Europeans.

This celebrated country has long been looked upon as a kind of fairy-land by the nations of the Western world. Its position on the globe is so remote that few – at least in former days – had an opportunity of seeing and judging for themselves.

In the autumn of 1842 he was appointed Botanical Collector to the Horticultural Society of London and began his travels to China the following spring. He went with the hope of exposing the ‘exaggerations and absurdities which have ever been written on China and the Chinese’; in fact, he found the country to be ‘just like other countries’. His introduction of tea plants to British India was of long-term commercial importance, but Fortune is chiefly remembered for introducing to Britain a wide range of plants, including varieties of skimmia, tree peony, kumquat, berberis, azalea and dicentra.

When we arrived at Hong-Kong, I divided my collections, and despatched eight glazed cases of living plants for England: the duplicates of these and many others I reserved to take home under my own care. I then went up to Canton, and took my passage for London in the ship ‘John Cooper’. Eighteen glazed cases, filled with the most beautiful plants of northern China, were placed upon the poop of the ship, and we sailed on the 22d of December. After a long but favourable voyage, we anchored in the Thames, on the 6th of May, 1846. The plants arrived in excellent order, and were immediately conveyed to the garden of the Horticultural Society at Chiswick. Already, many of those which I first imported have found their way to the principal gardens in Europe; and at the present time (October 20, 1846), the Anemone japonica is in full bloom in the garden of the Society at Chiswick, as luxuriant and beautiful as it ever grew on the graves of the Chinese, near the ramparts of Shanghae.

His timing was fortunate: he was sent to China at a time of peace when it was more accessible to Europeans. He was also able to make use of the new invention in 1833 of the Wardian case: a sealed glass case which increased the chances of bringing back living plants and other specimens. Furthermore, his travels coincided with a new trend for ornamental gardens in Britain which saw a huge increase in demand, particularly among the middle classes, for flowering shrubs and trees. There is little doubt, however, that his success was also due to his tenacious and courageous personality: from humble beginnings he achieved renown as a scientist and, while other plant hunters succumbed to gruesome ends overseas, Fortune made it home to live out his latter years in relative comfort and prosperity.

As I went down the river, I could not but look around me with pride and satisfaction; for in this part of the country I had found the finest plants in my collections. It is only the patient botanical collector, the object of whose unintermitted labour is the introduction of the more valuable trees and shrubs of other countries into his own, who can appreciate what I then felt.

The Devon and Exeter Institution holds Fortune’s four major publications on China, all beautifully illustrated.