John Gabriel Stedman (1744-1797)

Please be aware that the historic title of this item contains outdated language and terminology which is harmful and offensive.

Narrative, of a five years’ expedition against the revolted negroes of Surinam in Guiana on the wild coast of South America from the year 1772 to 1777 (London, 1806)

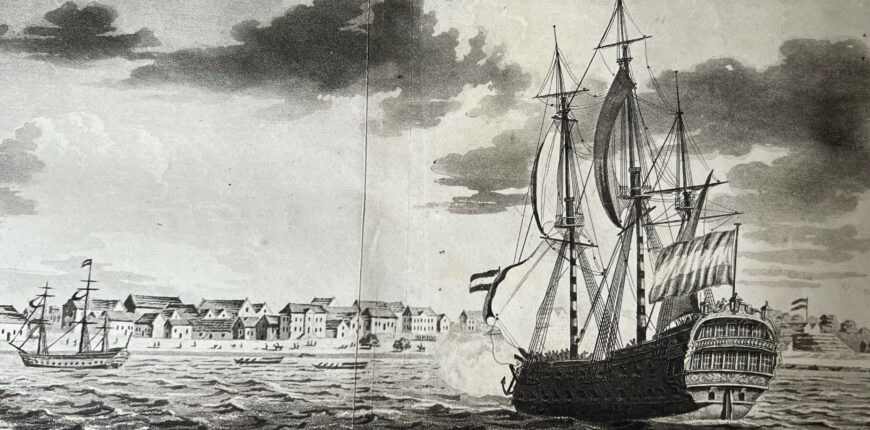

Stedman was born in 1744 in Dendermonde (which then was in the Austrian Netherlands) and left in 1772 after responding to a call for volunteers to serve in the West Indies. He was given the rank of Captain; his corps comprised 800 volunteers to be sent to Surinam (now Suriname) to assist local troops fighting against groups of previously enslaved people who had escaped from the eastern region of the colony. Stedman served in seven campaigns in the forests of Surinam, each averaging three months. He only engaged in one battle, which took place in 1774 and concluded with the capture of the village of Gado Saby. Soon after arriving in Surinam, Stedman met Joanna, an enslaved girl of mixed African and European ancestry. Though there is no evidence to suggest what Joanna’s feelings were towards Stedman, the two began a relationship which resulted in the birth of a son, John. Stedman’s primary difficulty was securing freedom for Joanna and their young son. Though he eventually succeeded in obtaining freedom for John, Joanna remained enslaved and Stedman returned to the Dutch Republic in June 1777 leaving both Joanna and his son behind in Surinam.

Soon after arriving in Surinam, Stedman met Joanna, an enslaved girl of mixed African and European ancestry. Though there is no evidence to suggest what Joanna’s feelings were towards Stedman, the two began a relationship which resulted in the birth of a son, John. Stedman’s primary difficulty was securing freedom for Joanna and their young son. Though he eventually succeeded in obtaining freedom for John, Joanna remained enslaved and Stedman returned to the Dutch Republic in June 1777 leaving both Joanna and his son behind in Surinam.

Joanna shewed great emotion, but immediately retired to weep in private. —What could I say or do ?— Not knowing how to answer, or sufficiently to admire her firmness and resignation, which so greatly exceeded my own, I determined, if possible, to imitate her conduct, and calmly to resign myself to my fate, preparing for the fatal moment, when my heart forebode me we were to pronounce the LAST ADIEU, and separate for ever.

Shortly after his return to the Dutch Republic, Stedman married a Dutch woman, Adriana Wierts van Coehoorn (1764-1829). Stedman was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in 1783, but he sold his commission the same year when, as a consequence of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, the Scots brigade was disbanded. His wife was the wealthy granddaughter of a well-known Dutch engineer and they settled in England at Hensleigh House in Tiverton, and had five children.

Shortly after his return to the Dutch Republic, Stedman married a Dutch woman, Adriana Wierts van Coehoorn (1764-1829). Stedman was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in 1783, but he sold his commission the same year when, as a consequence of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, the Scots brigade was disbanded. His wife was the wealthy granddaughter of a well-known Dutch engineer and they settled in England at Hensleigh House in Tiverton, and had five children.

Following Joanna’s death in Surinam in 1782, her son, John, moved to England to live with his father and was educated at Blundell’s School in Tiverton; John later served as a midshipman in the Royal Navy and died at sea.

This charming youth, having made a most commendable progress in his education in Devon, went two West India voyages [sic], with the highest character as a sailor; and during the Spanish troubles served with honour as a midshipman on board his Majesty’s ships Southampton and Lizard, ever ready to engage in any service that the advantage of his king and country called for.

Stedman is buried in the parish of Bickleigh in Devon.

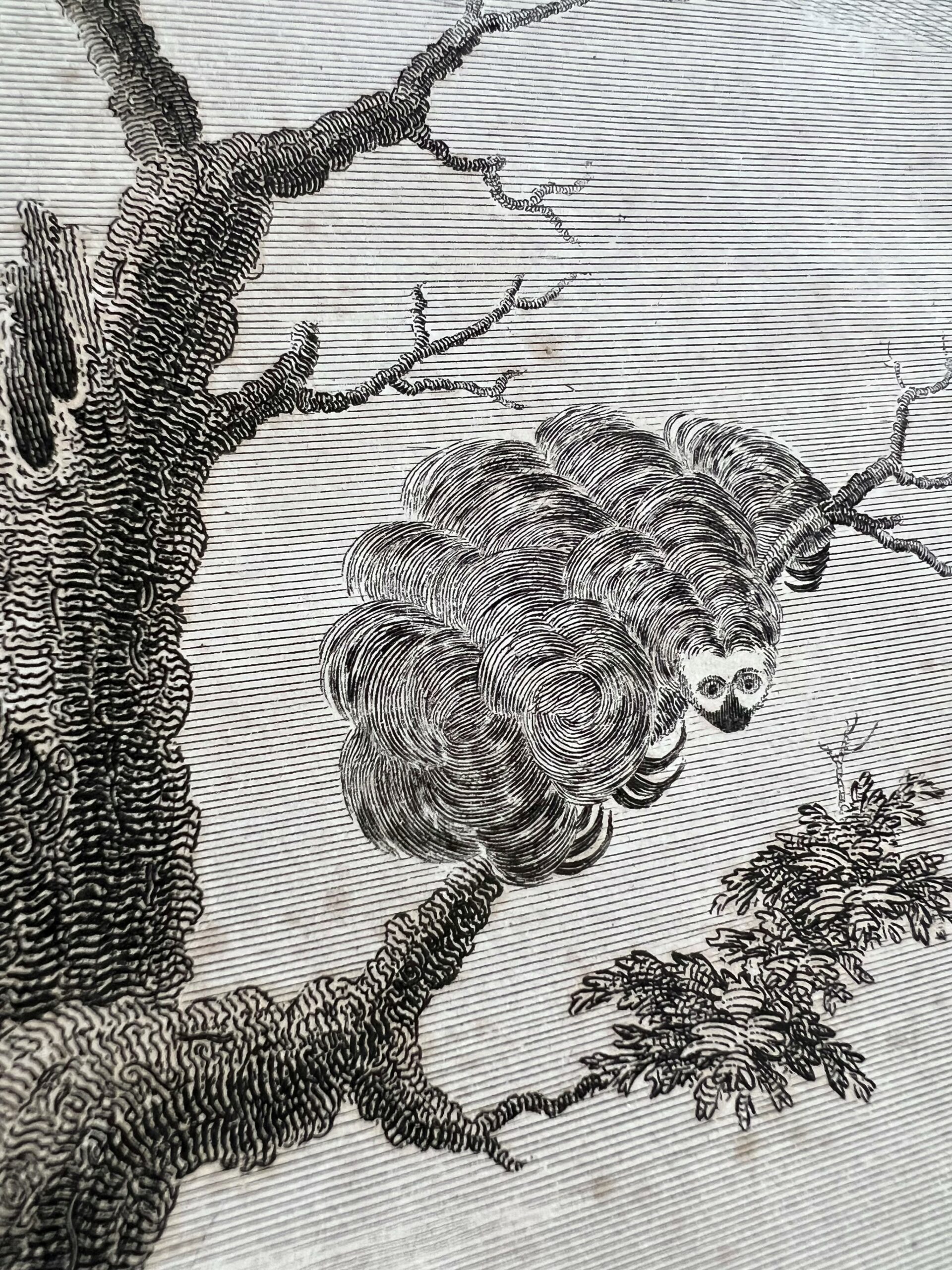

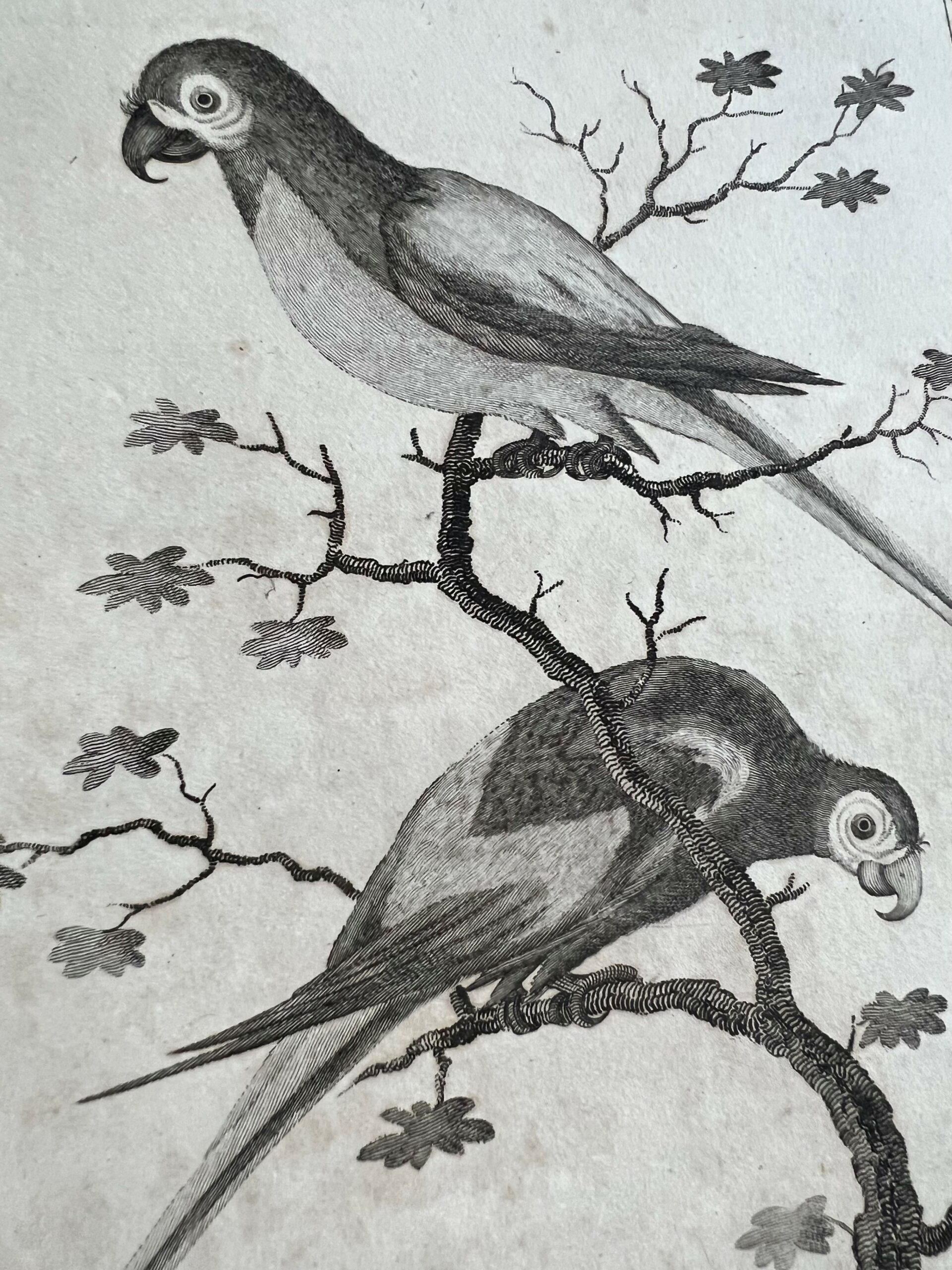

Stedman’s account of his time in Surinam is considered one of the most detailed accounts ever written of an eighteenth-century plantation society. There are extraordinary descriptions of animals, birds and fish, including of the capture of a giant anaconda:

I … perceived the head of this monster, distant from me not above sixteen feet, moving its forked tongue, while its eyes, from their uncommon brightness, appeared to emit sparks of fire.

Stedman includes, too, detailed descriptions of plantation life, including the ‘hardships and dangers’ of the process of sugar production. The first heavily edited edition of Narrative, of a five years’ expedition, published in 1796, is considered to distort Stedman’s views on race, slavery and social justice and present him as rather more pro-slavery than he was. In fact, it omits Stedman’s genuine admiration for the enslaved and free Africans and people of African descent that he came across in Surinam as well as many of his remarks about the misconduct and debauchery of European plantation owners.

Stedman’s views on slavery are complex. He saw that, ‘we only differ in colour, but are certainly all created by the same Hand’. He also hoped that his revelations about the treatment of enslaved people would be a call to action:

It is a painful circumstance, that the narrative of my travels must so frequently prove the record of cruelty and barbarity: but once for all I must declare, that I state these facts merely in the hope that it may, in some mode or other, operate for their future prevention.

However, despite his relationship with Joanna and his attempts to secure her freedom, he held back from supporting an immediate abolition of the institution of slavery:

For if such a measure should be rashly enforced, I take the liberty to prophesy, that thousands and thousands, both white and black, may repent, and more be ruined by it …

Even so, Stedman’s Narrative, of a five years’ expedition had considerable impact. It was an immediate bestseller, eventually published in over 25 editions and in six languages. Stedman’s descriptions and images of the treatment of enslaved people gave readers in the West a glimpse of the horrors of slavery and galvanised the new abolitionist movement; a letter to the Dorchester and Sherborne Journal, and Western Advertiser on Friday 3rd March 1797 states:

Even so, Stedman’s Narrative, of a five years’ expedition had considerable impact. It was an immediate bestseller, eventually published in over 25 editions and in six languages. Stedman’s descriptions and images of the treatment of enslaved people gave readers in the West a glimpse of the horrors of slavery and galvanised the new abolitionist movement; a letter to the Dorchester and Sherborne Journal, and Western Advertiser on Friday 3rd March 1797 states:

The following extract, descriptive of the cruelties exercised towards slaves in Surinam, is taken from Lieutenant Colonel Stedman’s Narrative … and although it will be hardly possible to peruse these and numerous other relations of shocking cruelties and barbarities, interspersed throughout the Narrative without a degree of painful-sympathy which will often rise into horror, yet is the writer sufficiently justified in narrating them, by the hope of exciting in the breasts of his readers a degree of indignation which will stimulate vigorous and effectual exertions for the speedy termination of the execrable Traffick in Human Flesh, which, to the disgrace of civilized society is still suffered to exist, and is, even in Christian countries, sanctioned by law! … Other accounts, equally shocking, are interspersed through the narrative – more than sufficient, surely, to keep the attention of the public awake to the grand object of the abolition of the slave trade.

Stedman produced 106 drawings and watercolours during his time in Surinam; many were engraved by the English poet and printmaker, William Blake (1757-1827), a strong opponent of slavery; in the process, the two men became lifelong friends.