Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778-1823)

Narrative of the operations and recent discoveries within the pyramids, temples, tombs, and excavations in Egypt and Nubia (London, 1820)

Belzoni was born in Padua, where his father was a barber, but his family originated from Rome and when Belzoni was 16 he went to work there, turning his ‘chief attention to hydraulics’. He intended taking monastic vows but in 1798 the occupation of Rome by French troops drove him from the city and altered the course of his career. Believing he was ‘destined to travel’, he became a ‘wanderer’, living ‘on my own industry, and the little knowledge I had acquired in various branches’.

Belzoni was born in Padua, where his father was a barber, but his family originated from Rome and when Belzoni was 16 he went to work there, turning his ‘chief attention to hydraulics’. He intended taking monastic vows but in 1798 the occupation of Rome by French troops drove him from the city and altered the course of his career. Believing he was ‘destined to travel’, he became a ‘wanderer’, living ‘on my own industry, and the little knowledge I had acquired in various branches’.

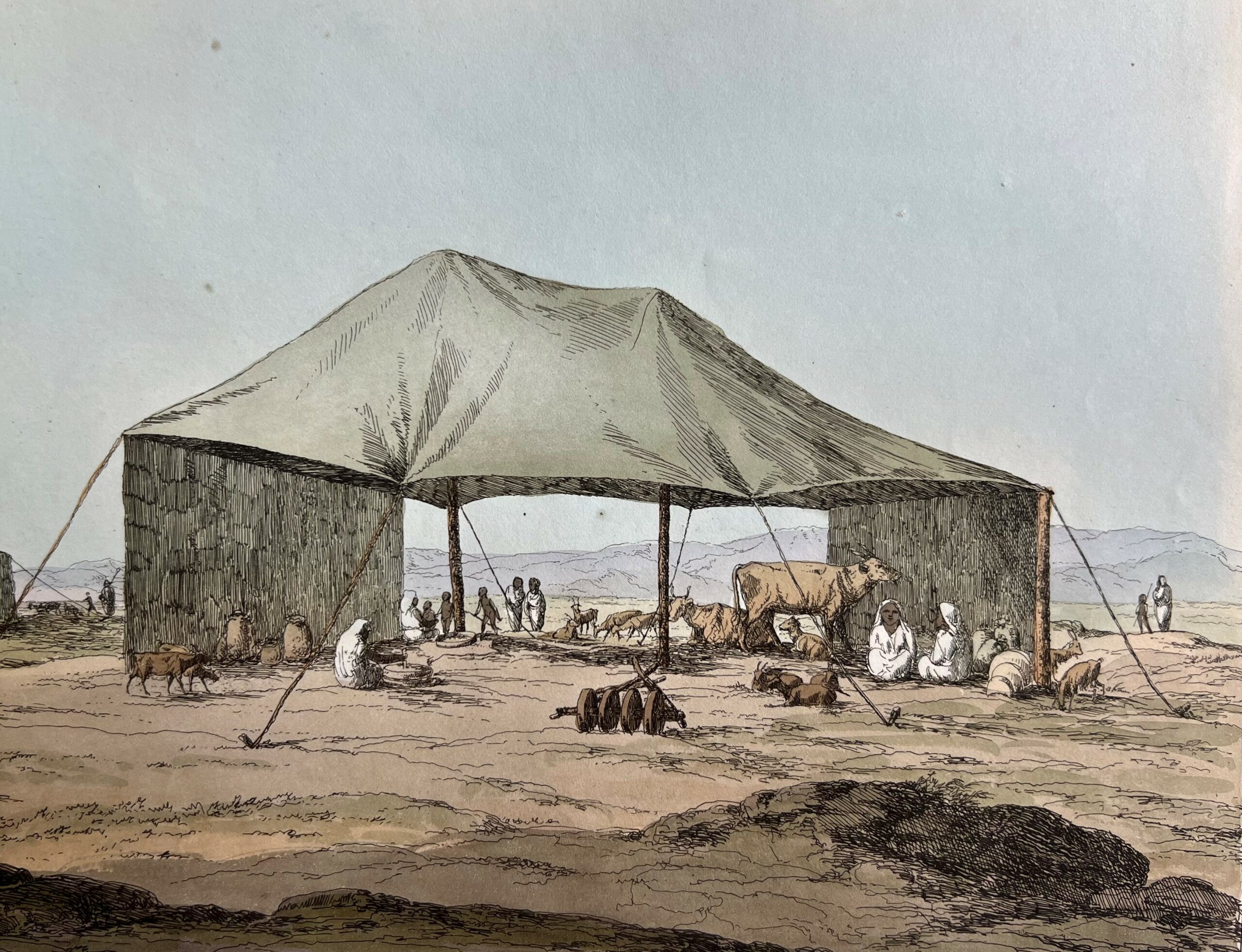

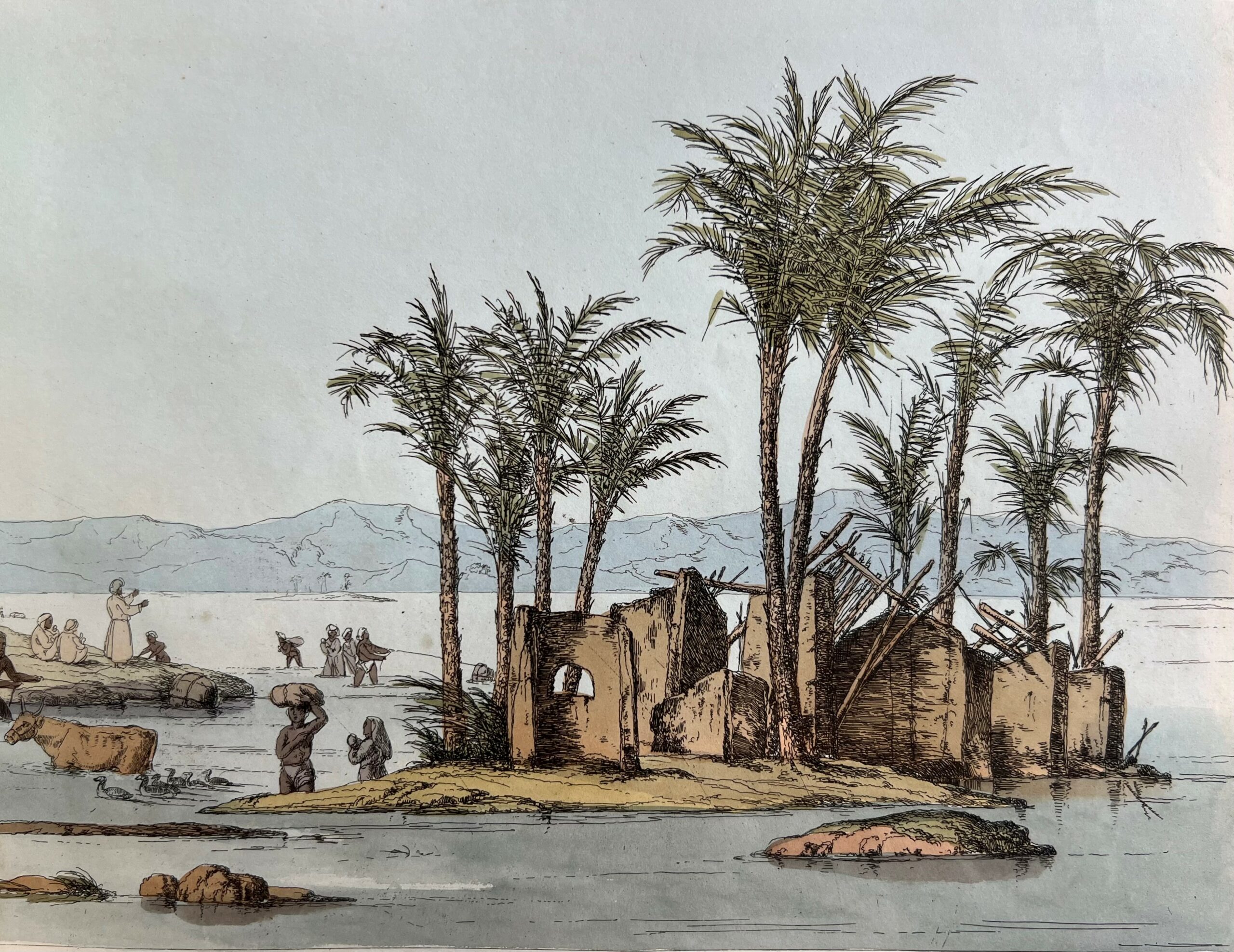

By 1803 Belzoni had moved to England and was making a living performing feats of strength and agility at fairs and circuses. After a tour of performances in Spain, Portugal and Sicily, he went to Egypt in 1815 where he met Ismael Gibraltar, an emissary of Muhammad Ali (1769-1849). Muhammad Ali was undertaking a programme of agrarian land reclamation and irrigation works and Belzoni was keen to show him a hydraulic machine of his own invention for raising the waters of the Nile. Though the experiment with this engine was successful, Muhammad Ali did not approve the project and Belzoni, now without a job, continued his travels.

On the recommendation of the orientalist, John Lewis Burckhardt (1784-1817), Belzoni was sent by Henry Salt (1780-1827), the British consul to Egypt, to the Ramesseum at Thebes. He removed the colossal bust of Ramesses II, commonly called ‘the Young Memnon’, and shipped it to England where it is still on display at the British Museum. The bust weighs over 7 tons and it took Belzoni 17 days and 130 men to tow it to the river.

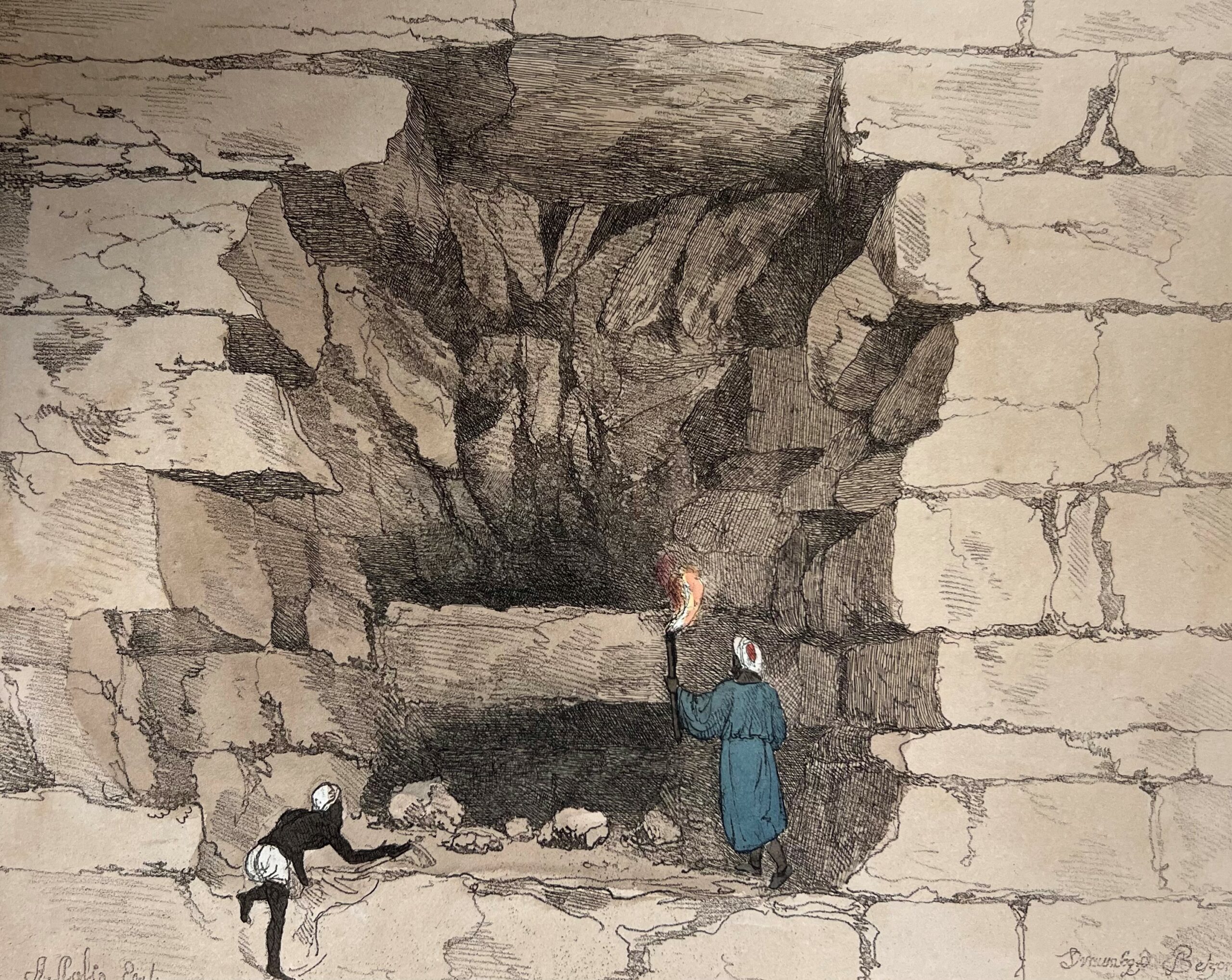

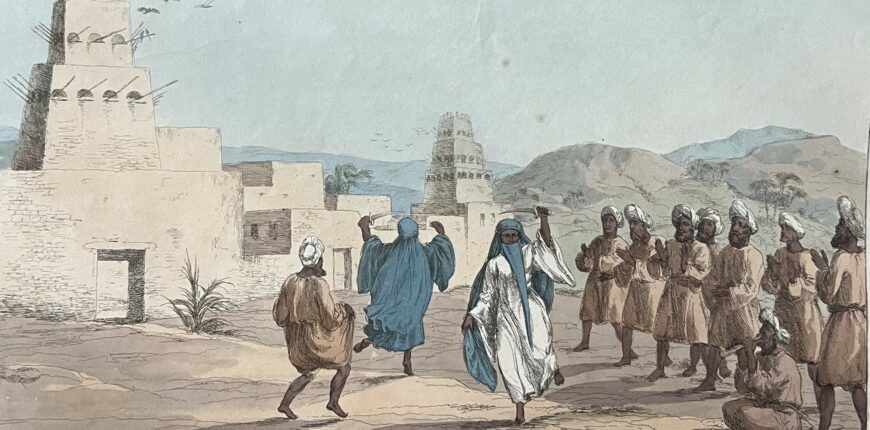

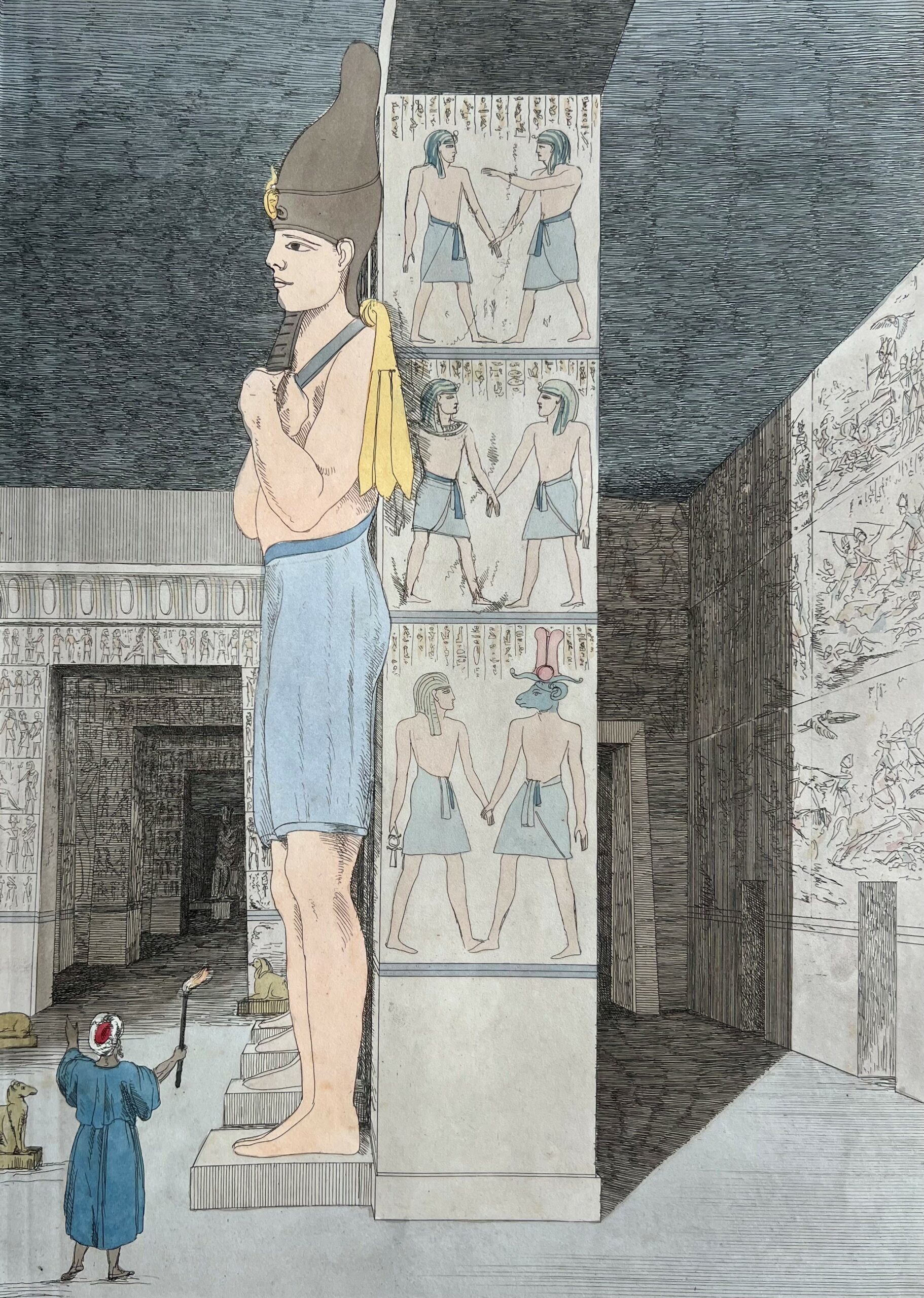

Belzoni also investigated the great temple of Edfu, visited Elephantine and Philae, cleared the great temple at Abu Simbel of sand, made excavations at Karnak, and opened up the sepulchre of Seti I (sometimes referred to as ‘Belzoni’s Tomb’). He was the first to penetrate into the second pyramid of Giza, and the first European in modern times to visit the oasis of Bahariya. He also identified the ruins of Berenice on the Red Sea.

Belzoni left Egypt in 1819, and reached England in 1820.

Belzoni left Egypt in 1819, and reached England in 1820.

On my arrival in Europe, I found so many erroneous accounts had been given to the public of my operations and discoveries in Egypt, that it appeared to be my duty to publish a plain statement of facts.

Belzoni’s Narrative of the operations and recent discoveries with the pyramids, temples, tombs, and excavations in Egypt and Nubia (including a ‘trifling account’ of the women of Egypt, Nubia and Syria by Belzoni’s wife, Sarah) was a huge success. Belzoni even leased the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly for a year to exhibit his Egyptian artefacts; the objects were subsequently sold in 1822. Seeking even greater fame, Belzoni determined to find the source of the Niger; he died of dysentery in West Africa in December 1823.

Many of the British Museum’s finest Egyptian antiquities can be traced back to Belzoni. His sometimes rough methods and lack of documentation of finds fill modern archaeologists with horror, yet he acted from a genuine desire to increase knowledge of ancient Egypt and is a true pioneer in the field. His discoveries laid the foundation for the scientific study of Egyptology; Howard Carter (1874-1939), the discoverer of Tutankhamun’s tomb about a hundred years ago, summed up Belzoni as ‘one of the most remarkable men in the entire history of archaeology’.

The 44 plates, presented in a separate volume, are nearly all hand-coloured; about half of them were produced by one of the most important figures in the development of British lithography, Charles Joseph Hullmandel (1789-1850), making this the first major publication to use this technique.