George Adams (1750–1795)

Essays on the microscope (1787)

When George Adams the Elder died in 1772 his family business of making scientific and mathematical instruments passed to his son, George Adams the Younger.

When George Adams the Elder died in 1772 his family business of making scientific and mathematical instruments passed to his son, George Adams the Younger.

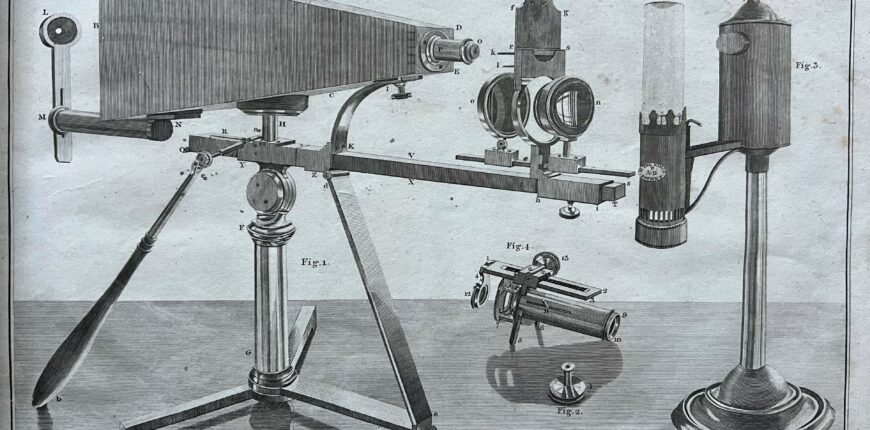

As well as the family business, George Adams also inherited his father’s role as mathematical instrument maker to George III and in 1787 he was appointed optician to the Prince of Wales. Two of his scientific instruments in the King’s collection demonstrate mechanical power for lifting heavy objects: the first instrument demonstrates pulleys and levers and the second shows the inclined plane, wedge and endless screw.

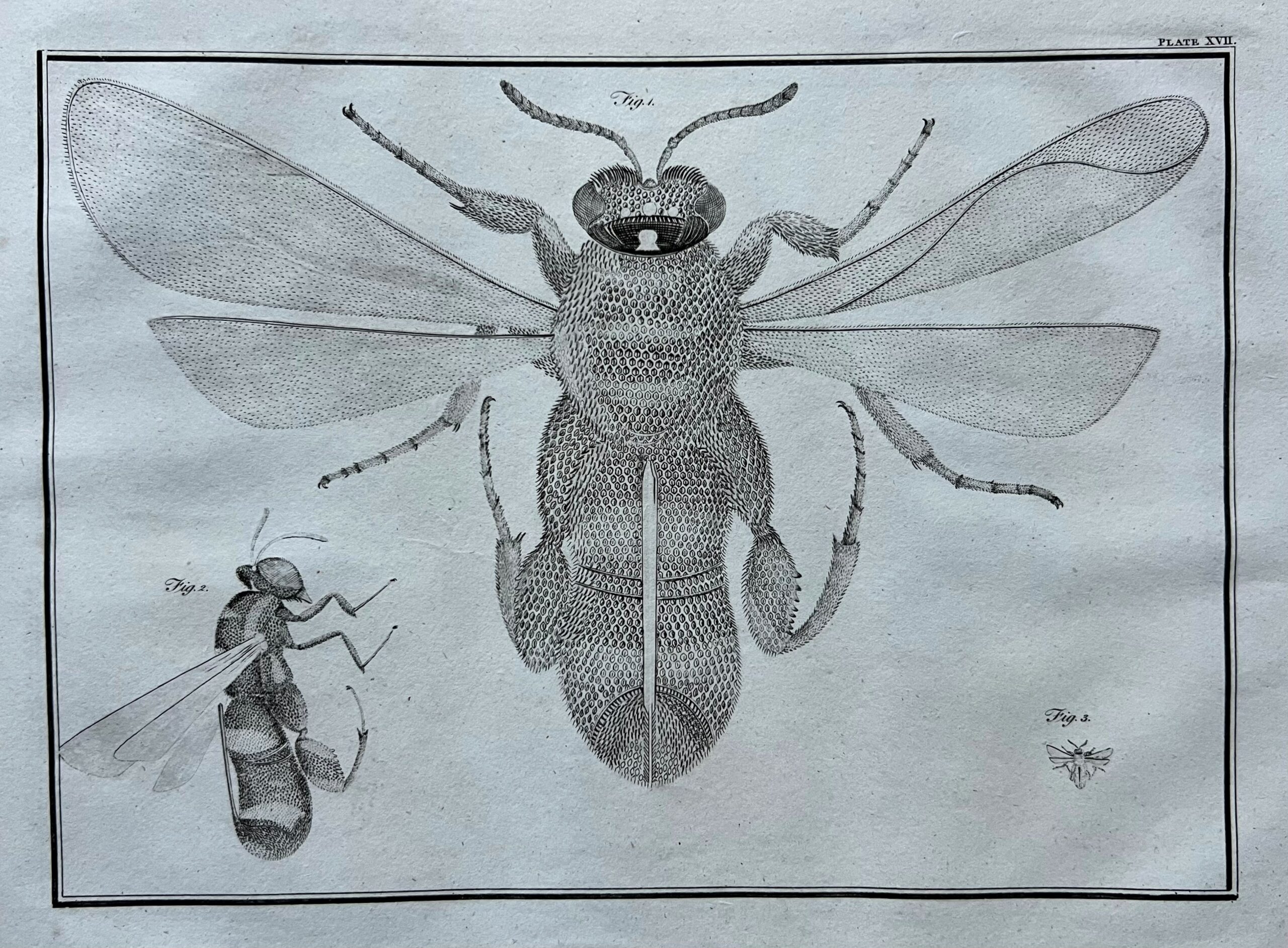

Around a century after Robert Hooke (1635–1703) published his famous Micrographia (1665), Adams invented a type of microscope called a lucernal microscope that projected an image onto a screen using an oil lamp as a light source.

In the 1780s he began writing scientific handbooks; his great work of Essays on the microscope, was published in 1787 and builds on the previous work of his father, Micrographia illustrata: or the microscope explained (1771). To avoid being ‘materially injured’, the remarkable accompanying plates to Essays on the microscope were issued separately for the purchaser to have bound as desired. At the Devon and Exeter Institution, these plates form a companion volume.

“The microscope extends the boundaries of the organs of vision, enables us to examine the structure of plants and animals; presents to the eye myriads of beings, of whose existence we had before formed no idea; opens to the curious an exhaustless source of information and pleasure; and furnishes the philosopher with an unlimited field of investigation. It leads, to use the words of an ingenious writer, to the discovery of a thousand wonders in the works of his hand, who created ourselves, as well as the objects of our admiration; it improves the faculties, exalts the comprehension, and multiplies the inlets to happiness ; is a new source of praise to him, to whom all we pay is nothing of what we owe; and while it pleases the imagination with the unbounded treasures it offers to the view, it tends to make the whole life one continued act of admiration.”