Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s Evenings at Home; or, The Juvenile Budget Opened

Parents all over the country are preparing for what could be many months of ‘home schooling’ – but it’s easier said than done. This little book – a two-hundred-year-old ‘domestic plan … for promoting the instruction and entertainment of the younger part of the household’ – may be just what they need.

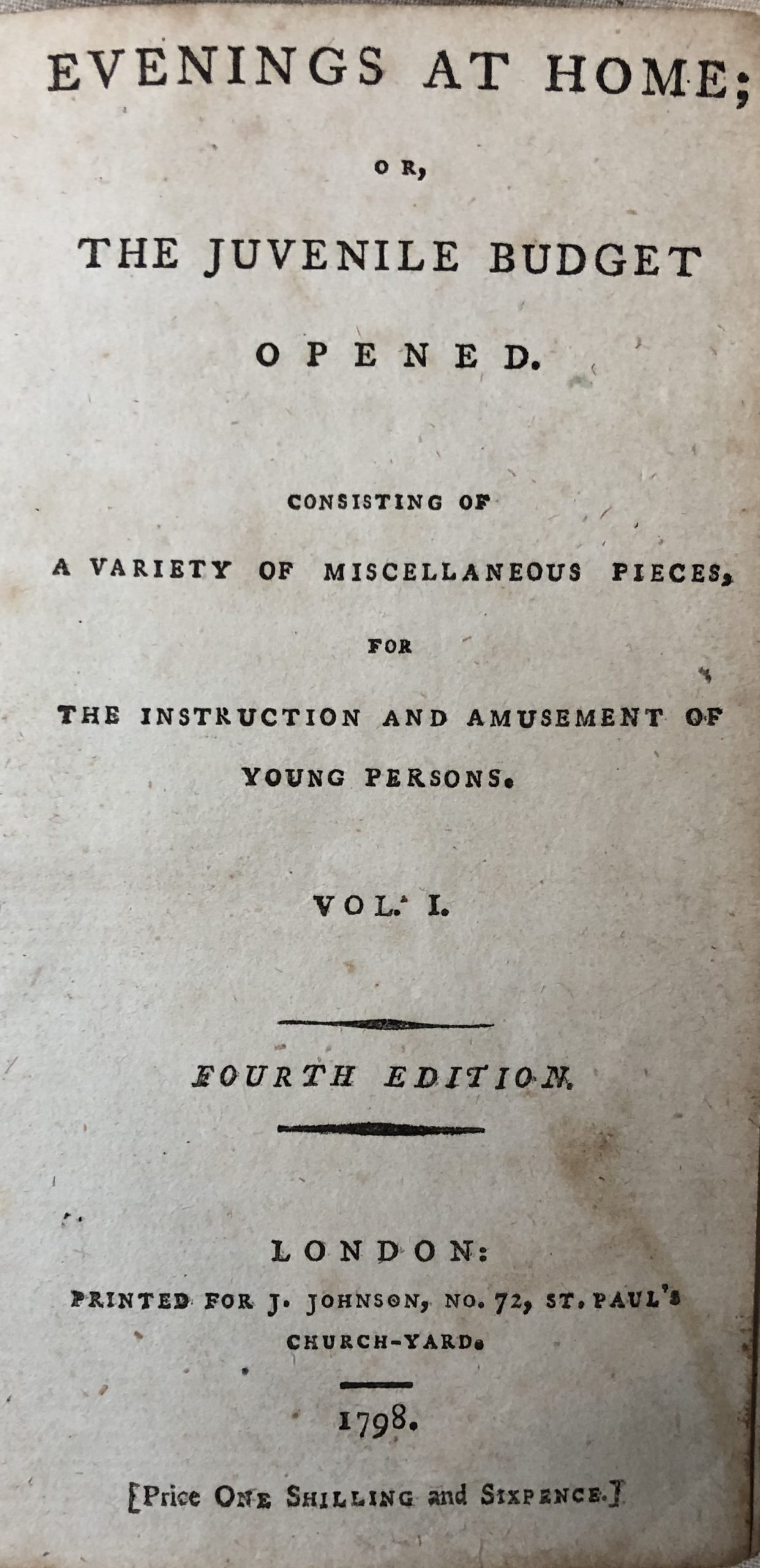

Evenings at Home was published in six volumes from 1792 to 1796. At the time, there was no formal education system for children. There were charity schools for the poor, Sunday schools for children who worked during the week, free grammar schools and ‘dame’ schools, but the children of wealthier families were taught at home.

The Enlightenment prompted a ‘new pragmatism in “home education”’.[1] The philosopher and empiricist John Locke (1632-1704) published a treatise on education in 1693 in which he described the child’s mind at birth as a tabula rasa – a clean slate that acquires knowledge through experience and sensory perception.

In 1762, the philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) expounded similar theories in his treatise, Émile, or On Education. The young Émile puts aside his books and learns through practical activities and experiments – going for a walk, singing, flying a kite, running around barefoot and even playing games in the dark.

Rousseau’s treatise was debated in fashionable society and within clubs and coffee-houses throughout the country. Richard Edgeworth (1744-1817), a member of the Birmingham Lunar Society and an engineer in telegraphy, electricity and agricultural technology, was among those who converted to ‘Rousseauism’. He applied its principles to the education of his eldest son, Richard, but the experiment was, by all accounts, a disaster. A practical education had ill-equipped Richard for steady work and, having finally settled on the navy, he jumped ship, literally, and died in America, greatly in debt.

Undeterred, Edgeworth planned his own treatise on education in collaboration with his daughter, Maria (1768-1849). Their three-volume work, Practical Education, appeared in 1798 – the culmination of over a century of Enlightenment thinking. The Gentleman’s Magazine described it as ‘education á-la-mode, in the true style of modern philosophy’.[2]

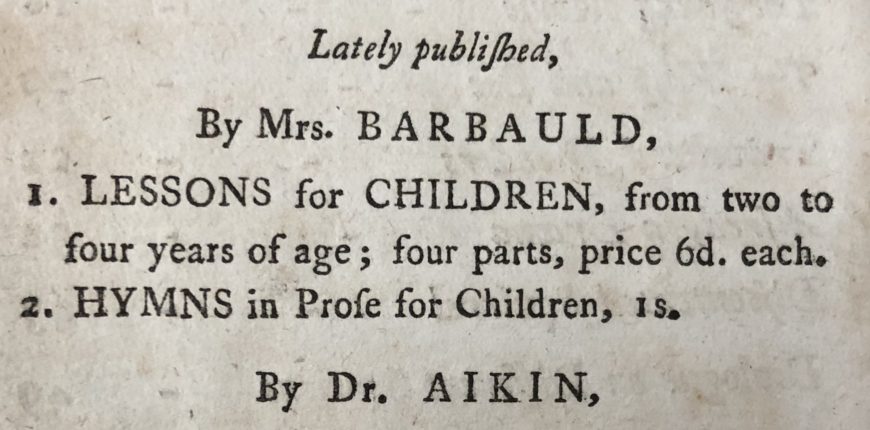

Anna Laetitia Barbauld (1743-1825) was one of several authors to respond innovatively to changes in the educational climate towards the end of the 18th century. Her practical style of home teaching was extolled by the Edgeworths.

“The first books which are now usually put into the hands of a child are Mrs. Barbauld’s Lessons; they are by far the best books of the kind that have ever appeared … The poetic beauty, and eloquent simplicity of many of Mrs. Barbauld’s Lessons, cultivate the imagination of children, and their taste, in the best possible manner.”

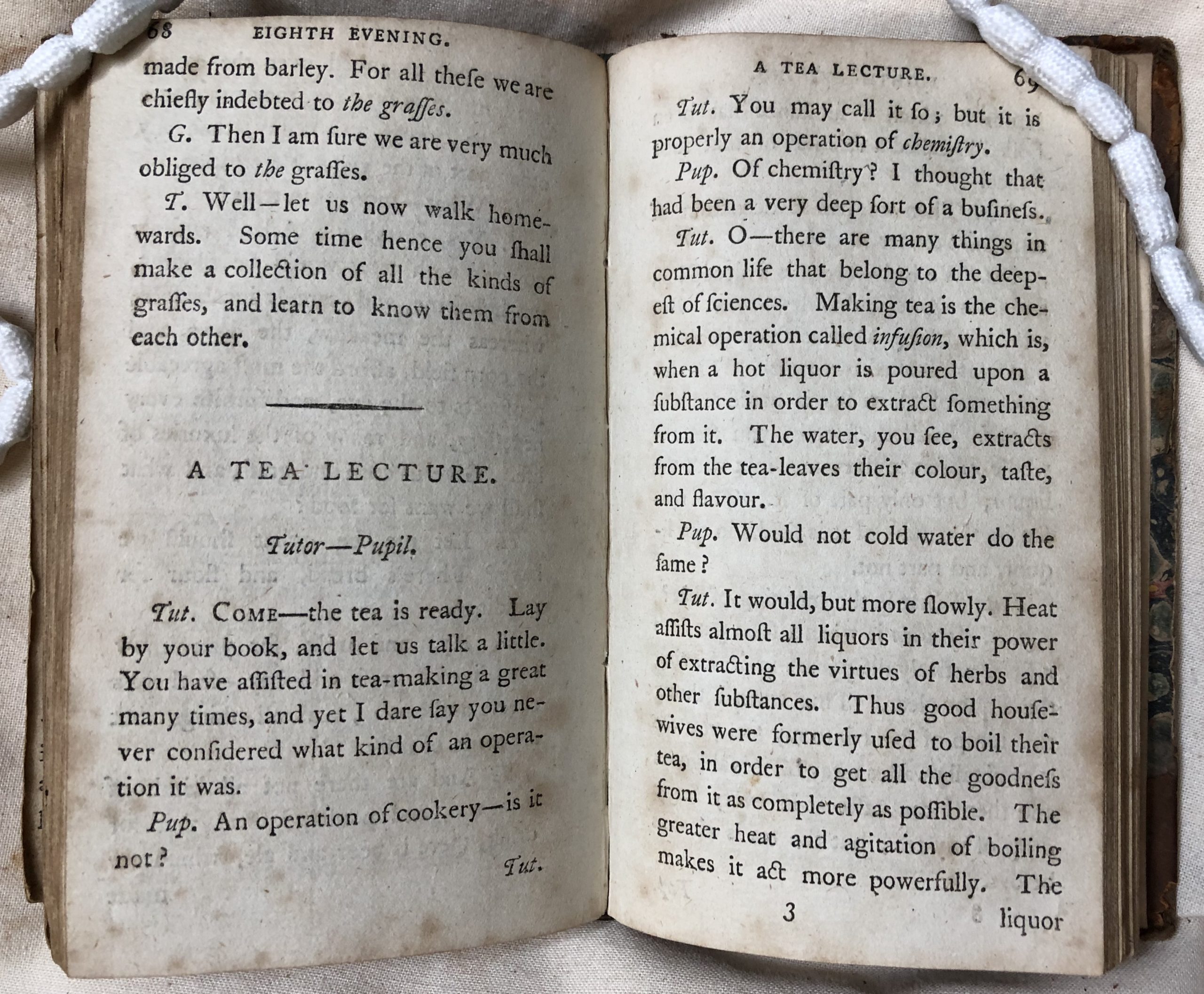

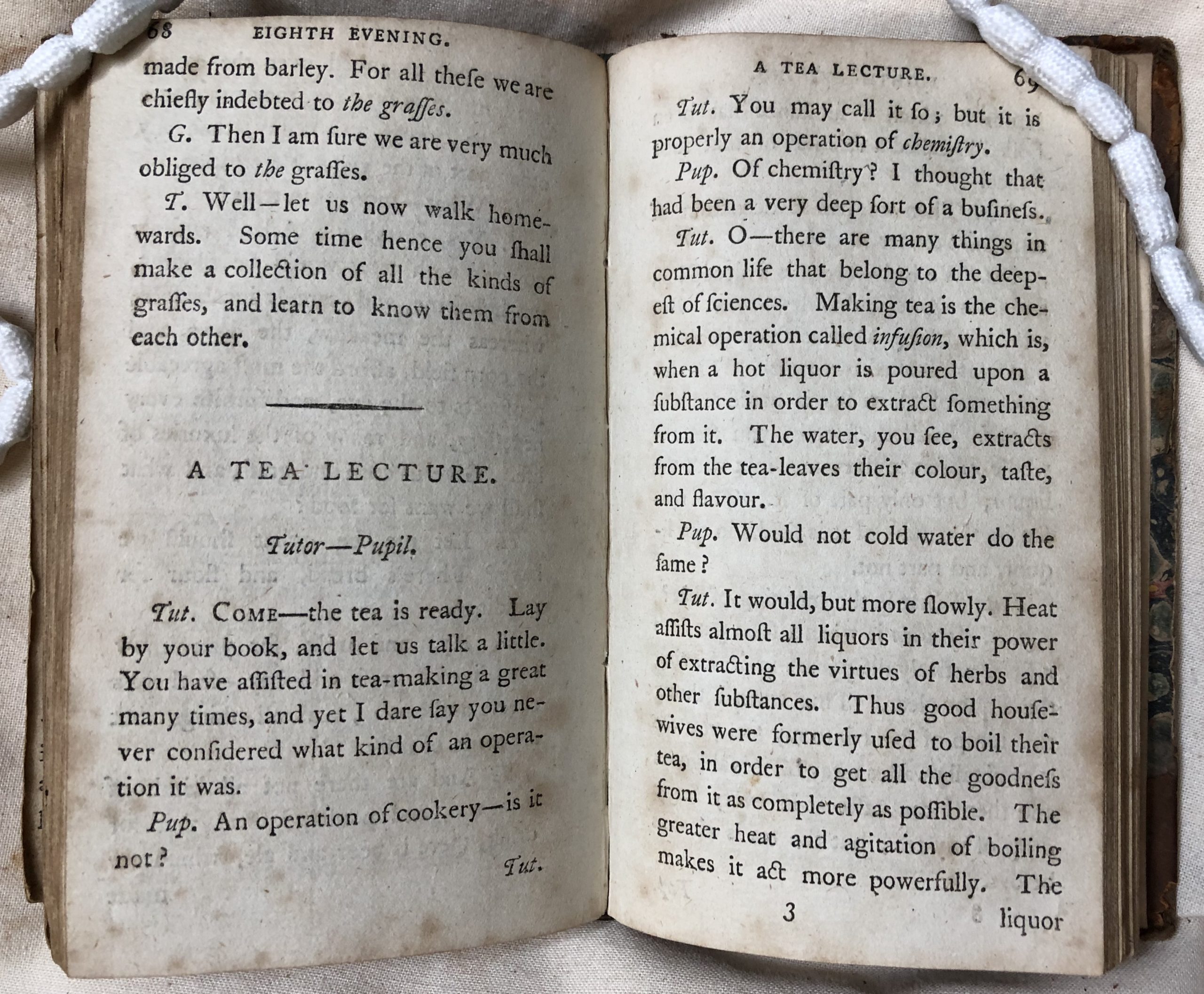

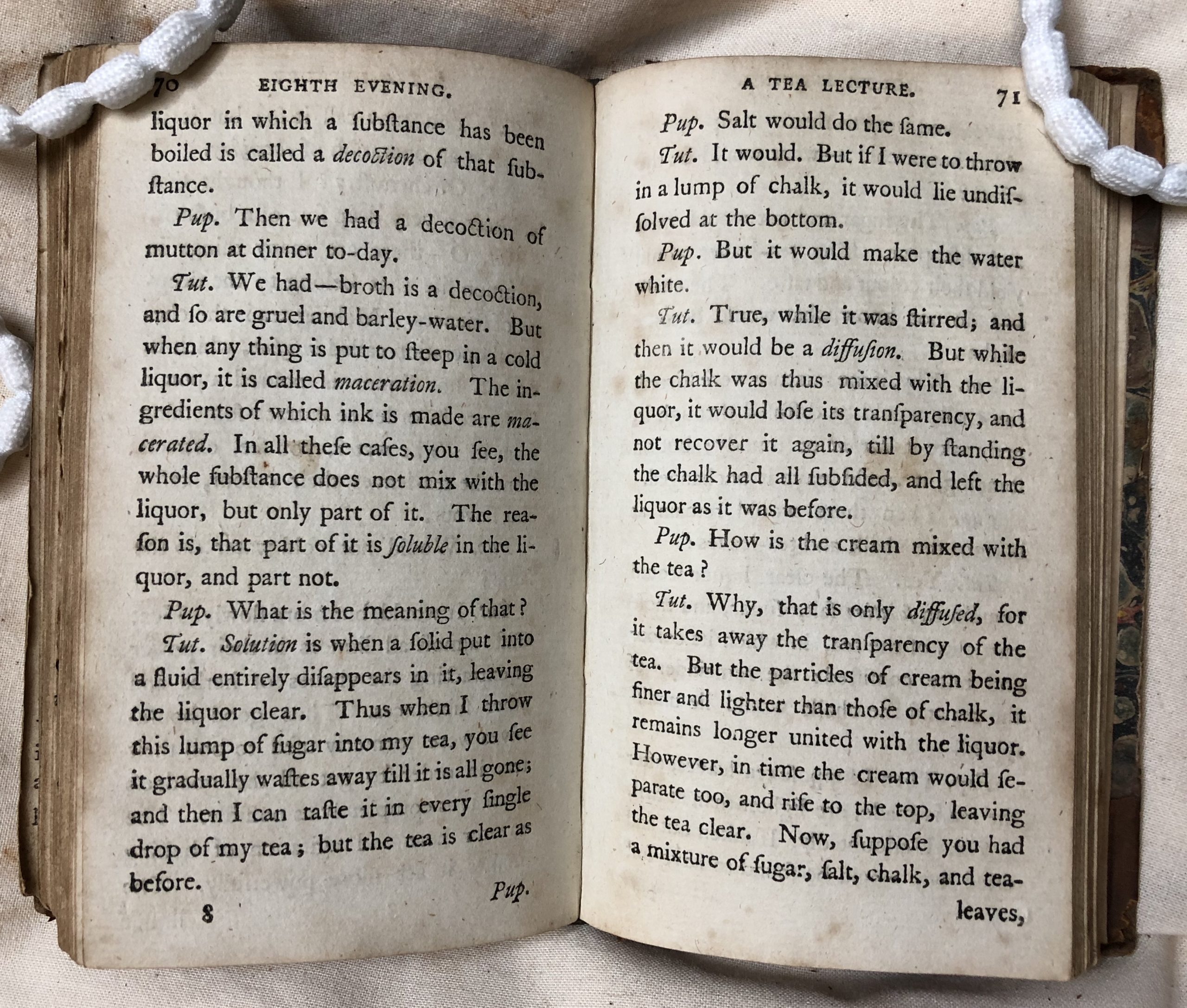

Barbauld revolutionised books for children. She used ‘good paper, a clear and large type and large spaces’ between the lines of text. Her lessons and lectures, drawn from everyday life, take the form of lively conversations between a mother and child, or between a tutor and pupil, and all subjects are covered, from botany and zoology to mathematics, chemistry and astronomy.

Barbauld’s books endured for several generations – the rather distressed condition of our copy is probably not unusual.

At a price of one shilling and sixpence, Evenings at Home was affordable only to relatively well-off families. In the introduction we meet the fictional family of Fairborne who live in a ‘mansion-house’ in ‘the pleasant village of Beachgrove’. The house is ‘seldom unprovided with visitors’ and all are encouraged to participate in the children’s ‘instruction and entertainment’. Those visitors ‘accustomed to writing’ produce a miscellany of stories, fables, poems and dialogues, ‘adapted to the age and understanding of the young people’. Each item is deposited in a box and locked away until the holidays.

“It was then made one of the evening amusements of the family to rummage the budget, as their phrase was. One of the least children was sent to the box, who putting in its little hand, drew out the paper that came next, and brought it into the parlour … and after it had undergone sufficient consideration, another little messenger was dispatched for a fresh supply; and so on, till as much time had been spent in this manner as the parents thought proper.”

In keeping with Enlightenment ideals, each practical evening lesson encourages a spirit of enquiry. Here, the dialogue between the tutor and pupil turns to tea making – ‘properly an operation of chemistry’.

I like to think that many children have loved and treasured this book over the last two hundred years. I don’t know how it came to the Devon and Exeter Institution, but I am intrigued at how modern it feels. We would probably agree with our enlightened forebears that young children learn through play and experience. Perhaps an enforced period of home-schooling is an opportunity to explore more practical ways of learning within our homes – and, after all, there’s little that can’t be resolved with a nice cup of tea.

You can read a later edition of Evenings at Home online here: https://archive.org/details/eveningsathomeo02aikigoog/page/n12/mode/2up

Emma Laws, Director of Collections and Research

[1] Brian Alderson, ‘Miniature libraries for the young’, The private library, 3rd series, vol. 6, no. 1 (Spring 1983), page 11.

[2] ‘Review of recent publications’, The gentleman’s magazine, vol. 70, (part 1), no. 5 (May 1800).