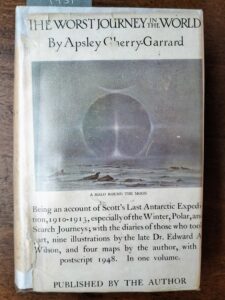

The worst journey in the world

Apsley Cherry-Garrard, 'The worst journey in the world', (1951). Classmark: G 15

This Book of the Month blog was researched and written by Tony Rhodes, library volunteer at the Devon and Exeter Institution library.

Our Book of the Month was published 100 years ago in December 1922. Whilst the author returned from the Antarctic in 1913, World War I intervened to delay the writing and publishing of his account of Capt. Robert Falcon Scott’s last voyage.

Apsley was born in Bedford in 1886, the son of a distinguished soldier who reached the rank of Major General, he had five sisters. Whilst short-sightedness was a problem at school, at Oxford he excelled at rowing, winning the Grand Challenge Cup at the 1908 Henley regatta. In 1907 Cherry-Garrard’s father died, leaving his only son a considerable fortune and the wherewithal to apply to join Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s second expedition to the Antarctic in 1910. His first application was turned down but Scott was later persuaded to take him on by Dr Wilson, as an assistant Zoologist and, at 24, the youngest member of the expedition. Apsley must have been a remarkable young man as he went on to become one of the most popular of the expedition members, warmly commended by Scott and later chosen by Wilson, along with “Birdie” Bowers as one of his two companions on the highly hazardous Winter Journey of 120 miles in darkness and at -70º F to collect Emperor penguin eggs from the penguin rookery at Cape Crozier. Sixteen months later he was a member of the search party which found the bodies of Scott, Wilson and Bowers and learned of the great sacrifice of Laurence “Titus” Oates and the tragic death of Petty Officer Edgar Evans.

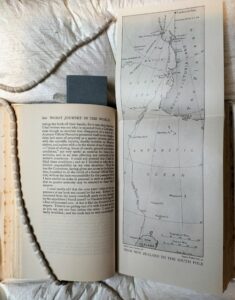

The Terra Nova set sail for the Antarctic in May 1910, Scott having already left for the Antipodes to continue with fundraising and other preparations, he later joined the expedition ship from New Zealand in November of that year. They arrived in Antarctica (Cape Evans) in January 1911 with 15 ponies, having already lost 2 of them at sea, 2 motor tractors, one having been lost whilst being unloaded, and 2 dog sledges. They carried with them a Union Flag given to them by Queen Alexandra and a sledging flag flown by Scott (which can still be seen in Exeter Cathedral).

Scott had heard of the arrival of his great rival Roald Amundsen on 22nd February, “they had 120 dogs and were going for The Pole, no science, no nothing, just The Pole” as described by Lieut. Wilfred Bruce on board the Terra Nova. According to Scott, the Terra Nova expedition’s objective was “to explore the entirely unknown region of King Edward’s Land, to investigate the nature and extent of the Great Ice Barrier Formation and to survey the higher regions of Victoria Land. There would be an intensive study of marine biology and a search for radium-bearing pitchblende”. Scott added, “I admit that the main object of the expedition is to reach the South Pole, but this is largely sentiment” (R. Pound, Scott of the Antarctic, 1966).

It is hard to discover which of the Journeys described in Apsley Cherry-Garrad’s account was actually The Worst Journey in the World as the expedition undertaken by Captain Scott, his “scientific staff” and fellow explorers encompassed several incredible and dangerous treks. The first of these, the Depot Journey of January to March 1911 involved thirteen men, each allowed only 12lbs of “private gear”. For almost three months they delivered rations and equipment to various depots in sub-zero temperatures, travelling over pack ice and across crevasse and boulder strewn terrain, in all covering 140 miles of the southern route where finally a ton of stores was deposited, giving it the name “One Ton Depot”. During the return to base three of the best ponies were lost.

Early on in this journey they came across the shredded tents containing stores left by Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition of 1907/9, including a Primus cooker and some food with which Scott cooked a meal! Conditions were so bad that, in February, three men returned to Base Camp with the weakest three ponies, unable to continue. In June 1911 the Winter Journey, with Wilson, Bowers and Cherry-Garrard covered 60 miles each way in complete darkness and in temperatures below -70 ° F, recorded at -77° F on one occasion. Five weeks later, on their return Scott described their trek as “the hardest that has ever been made”, this may have inspired Apsley to the title of his book. Despite the extreme hardship and appalling conditions, the party were able to reach the rookery and secure some eggs for later research.

In November Scott and four others started south to The Pole, passing the abandoned tractors of the advance party before catching them up. The air-cooled tractors main defect appears to have been overheating! One by one Scott’s ponies died, the last two had to be shot on the 9th December, providing food for the dogs. The party reached the Beardmore Glacier on December 10th, in conditions so bad ski and sledge runners sank in the soft snow, even working from 10 to 12 hours they only progressed five miles per day. By Christmas Day they reached 86° S and on New Year’s Eve they laid another cache. On January 4th two seamen, Crean and Lashly, together with Lieut. Evans set out to return to base, taking with them a message from Scott to his wife.

The final party for the push to the Pole with Scott were Dr. Wilson, Capt. Oates, Lieut. Bowers and Petty Officer Evans, they took with them one month’s provisions. By 9th January, despite the immense physical hardships, they were “only 85 miles from The Pole” on 13th “only” 51 miles (covering 8 1/2 miles a day) but with physical strength diminishing rapidly. Scott’s realisation, by 15th January, that Amundsen may have reached The Pole already must have had a drastic effect on morale. On 16th January they reached latitude 98° 42’ S by midday, two hours later Bowers spotted a black speck which gradually revealed itself to be a flag on a cairn. A Norwegian flag. Approaching the site were sledge tracks and dogs’ paw prints. The disconsolate party hoisted Queen Alexandra’s Union flag, took a (now) historic photograph and collected a message from Amundsen to the King of Norway, left for Scott to deliver in the event of disaster striking the Norwegian party during the return voyage.

Captain Scott and his four companions then commenced their 800 mile journey home, might this turn out to be The Worst Journey in the World? The expedition was in a sorry state; Wilson was half blinded by the glare of the snow, Evans’s frostbitten hands were in a bad way, one of Oates’s feet was injured and Scott had hurt his shoulder in a fall. By February the 11th they had two days’ food left, Bowers and Wilson snow blind, Evans vomiting and having dizzy spells. By the 17th his legs gave out and he became comatose, he died at 10pm. They reached Lower Glacier Depot and retrieved some rations, including pony meat. Spirits rose, by 23rd February Scott, writing in his journal “things are looking up as we are on the regular line of cairns, with no gaps right home”.

They were slowing down by the beginning of March, covering 3 1/2 miles in 4 1/2 hours, Oates’s feet were in terrible state. They were short of both food and paraffin to cook with, thus having to eat their meagre rations cold. On the following day Scott wrote “our fuel dreadfully low and the poor soldier (Oates) nearly done”. On the 16th or 17th Oates begged the others to go on without him but they refused. Meanwhile, just eleven miles north, at One Ton Depot, Cherry-Garrard and Dmitri, the dog team driver were preparing to leave for the base at Cape Evans, having reluctantly abandoned their search for Scott’s party. That night Oates went to sleep praying that he might not wake up, but he did. It was blowing a blizzard and he famously said “I am just going outside and may be some time”. The three remaining explorers never saw him again.

For the next eight days the tent was shaken by the blizzard and temperatures fell below -40° F. Unable to continue, Captain Scott wrote to his wife, his mother and friends, finally, on 29th March 1912 in the last pages of his journal a note ending with the words “we shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity but I don’t think I can write more_ R Scott. For Gods sake look after our people”. It was over seven months later, on 12th November 1912 when a search party led by Surgeon Lieut. E. L. Atkinson RN, including Apsley Cherry-Garrard discovered a “dark patch” which turned out to be the top six inches of a tent. Cherry-Garrard wrote, “it is all too horrible – I am almost afraid to go to sleep now”. The bodies of Robert Falcon Scott and his two companions were lying side by side in their sleeping bags. A large cross of Australian jarrah wood was later erected on Observation Hill, in sight of the camp at Cape Evans. On it is inscribed, at Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s suggestion, “To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield”.