The ‘impulse of curiosity’: Hugh Clapperton’s explorations into the African interior

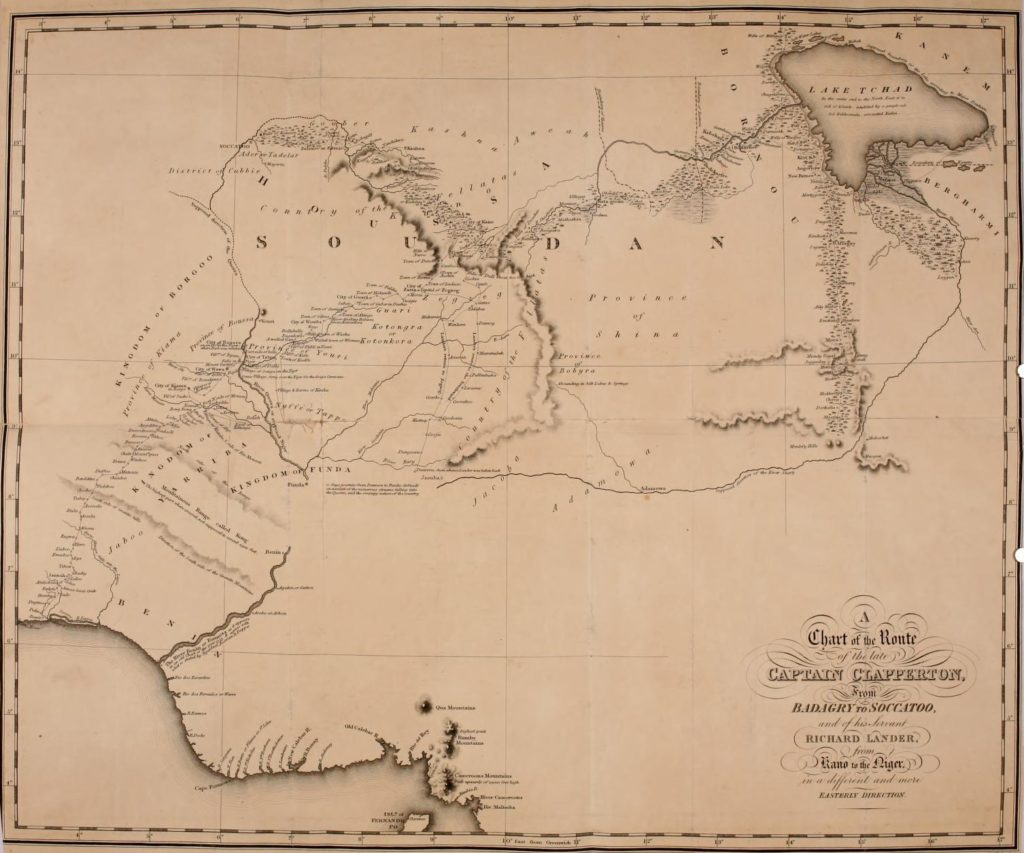

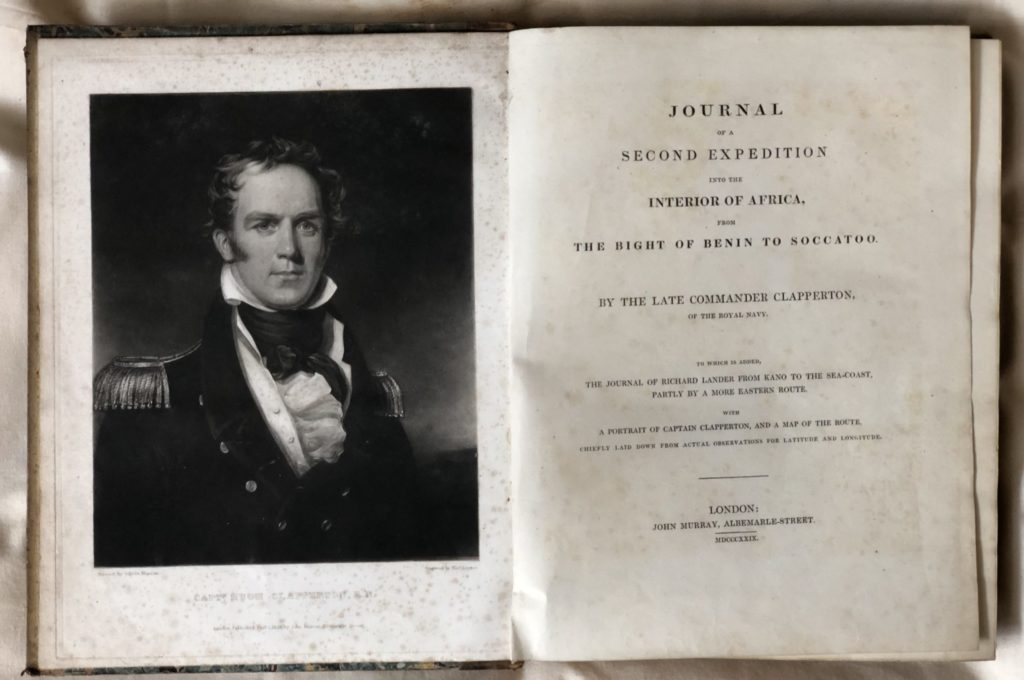

Furloughed on half pay following the end of the war with France, Captain Hugh Clapperton (1788–1827) looked to augment his income with an intrepid exploration into the African interior.

On 9 June 1788 several members of London’s elite, led by Sir Joseph Banks (1743–1820), founded an Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa, also known as the African Association. They hoped to remedy what they saw as a shortcoming of their Age of Enlightenment:

‘The close of the eighteenth century was distinguished for an extraordinary ardour in the pursuit of geographical discoveries. Navigation had assumed a boldness which naturally gave an impulse to geographical enquiries; and while our ships visited the remotest parts of the globe, it seemed disgraceful that we should still remain in ignorance of the interior of Africa.’

William Desborough Cooley, The history of maritime and inland discovery (1830)

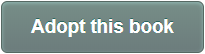

The founding of the Association marked, for Europeans at least, ‘a new era in the history of African discovery’. It aimed to chart the unconventional course of the Niger and to pinpoint the precise location of the city of Timbuktu on European-made maps.

Members who pledged five guineas a year to fund geographical expeditions to Africa did so, according to Cooley in 1830, from an ‘impulse of curiosity’ and with a genuine thirst for scientific and medical knowledge. Many, too, were passionate abolitionists who sought to interrupt the traffic of slaves from the West Coast of Africa. However, the aims of the Association also coalesced with those of government. If successful, explorations could lead to territorial and political expansion as well as opportunities for commerce with the African continent – Timbuktu was reputed to be extremely wealthy and the Niger, though largely unknown to Europeans, was already an important trade route.

Early attempts to penetrate the interior of Africa ended in disaster. John Ledyard (1751-1789) accidentally poisoned himself three months after arriving in Alexandria and died in Cairo on 10 January 1789. The same year, tribal wars forced another explorer, Simon Lucas, to abandon an expedition south from Tripoli. In 1790, Daniel Houghton (1740-1791) explored further inland than any European before him; he arrived at the Saharan village of Simbing in September 1791 but was never heard of again. Mungo Park (1771–1806) set foot on the African continent in June 1795 and became the first European to catch sight of the Niger. He embarked on a subsequent expedition to Africa in 1803 but drowned in the Bussa Rapids following an ambush. The following year, the African Association sponsored Henry Nicholls in yet another failed attempt to reach the Niger; within a year, he had died of malaria.

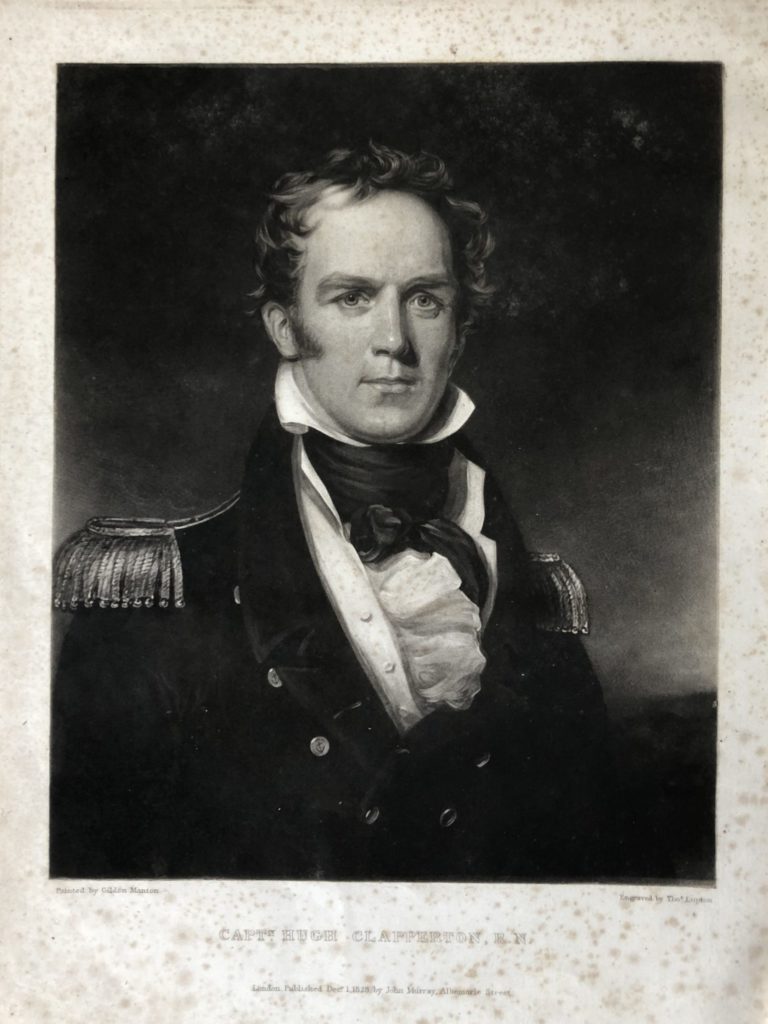

The British government had no shortage of intrepid explorers eager to succeed where others had failed. Following yet another doomed expedition by George Francis Lyon (about 1795–1832) – he did at least return home – the government commissioned Walter Oudney (1790–1824), a doctor and naturalist, to proceed to Tripoli, accompanied by a naval captain, Hugh Clapperton (1788–1827), who had been ‘furloughed’ on half pay since the end of the wars with France. They were later joined by Major Dixon Denham (1786–1828). Their mission was to travel from Tripoli across the Sahara to the province of Bornu – ‘a route which the British consul asserted was as open as that from London to Edinburgh’.

Hugh Clapperton was a ‘handsome, athletic, powerful man’ and an experienced explorer. The expedition was relatively successful – only Walter Oudney didn’t make it home – and, despite clashes between Clapperton and Denham, all three men became the first Europeans to set eyes on Lake Chad. They even reached their destination, Bornu, on 17 February 1823 and were reportedly well-received by the sultan Sheikh al-Kaneimi. Alone, Clapperton made it as far as Sokoto where, in return for a watch, telescope and thermometer, he is reported to have ‘received the most flattering attentions, and every mark of kindness’ from the sultan, Muhammed Bello.

On his return to England, Clapperton impressed the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Henry Bathurst (1762–1834), who didn’t hesitate in sending him on a second exploration to Africa:

‘… considering this so favourable an opportunity … for extending the legitimate commerce of Great Britain with this part of Africa, and at the same time adding to our knowledge of the country…’

(Hugh Clapperton, Journal of a second expedition into the interior of Africa, 1829)

Clapperton, now promoted to Commander, went out on HMS Brazen, a ship serving with the West Africa Squadron tasked with patrolling the coast of West Africa and suppressing the Atlantic slave trade. Clapperton was accompanied by his servant, Richard Lander (1804–1834), Captain Pearce and doctors Morrison and Dickson. Dickson disembarked alone near Whydah and was never heard of again. The others sailed on to Benin and in December 1825 proceeded overland towards the Niger. Within a month both Pearce and Morrison had died of fever. Clapperton and Lander made it as far as Sokoto to renew a dialogue with Bello. According to Lander, all went well until they announced their intention to travel on to Bornu to visit Sheikh al-Kaneimi – evidently, they hadn’t realised that Bello and the Sheikh al-Kaneimi were now at war with each other.

Detained in Sokoto, Hugh Clapperton died from dysentery and malaria. Richard Lander was sole survivor of the expedition. He buried his master at Jungavie, a small village five miles south-east of Sokoto, and on his return to England published his master’s journal, appending his own account of the journey home and adding a biographical sketch by Clapperton’s uncle, Lieutenant-Colonel S. Clapperton. In a letter to the Consul in Tripoli on 27 May 1817 Lander wrote of his ‘kind-hearted and benevolent’ master: ‘he had always behaved like a father to me since I left England.’

Lander summarised Clapperton’s African adventures:

‘He has not contributed much to general science, but, by his frequent observations for the latitude and longitude of places, he has made a most valuable addition to the geography of Northern Africa…’

(Hugh Clapperton, Journal of a second expedition into the interior of Africa, 1829)

In 1830, Richard Lander and his brother John set out once more to explore the Niger and, finally, succeeded in determining its course and termination. Richard Lander died in a subsequent expedition to Africa, shot with a musket. In 1831 the African Association was absorbed into the Royal Geographical Society, founded the previous year; its various explorers had failed to reach Timbuktu but an independent explorer, Alexander Gordon Laing (1794–1826), became the first European to reach the city in August 1826. He was killed there five weeks later.

The Library at the Devon and Exeter Institution has a significant collection of accounts of travels during the Age of Enlightenment, including several of explorations in Africa. At the time they were published, these various accounts greatly increased European knowledge of the geography of Africa. They may even have helped to dispel long-held European myths relating to the peoples of Africa. However, early attempts to explore the interior of the African continent undoubtedly paved the way for the imperialist ‘Scramble for Africa’ from the 1880s onwards which saw the continent divided into colonial territories. How do we read these accounts today? The answer, I think, is carefully, honestly and collaboratively.

For centuries, European institutions, museums and libraries have been custodians of black history. The Museums Association offers advice on how we can begin to address the colonial context of our collections and become allies and activists for change, for example, incorporating indigenous viewpoints into interpretation and working with diverse communities to amplify voices that are not being heard and to invite them to tell more and different stories about collections, however uncomfortable.

In November 2019, the CILIP International Library and Information Group held a conference on ‘Decolonising library collections and practices: from understanding to action’. Christine Megowan, Cataloguing Librarian of Rare Books at Cardiff Metropolitan University, proposed steps towards decolonising heritage collections in particular:

‘Primary sources are the lens through which we view history. As the traditional (gate)keepers of primary sources, cultural heritage professionals wield power (whether we like it or not) in shaping historical narratives which inform how we interpret the present. Libraries, Archives, and Museums are rooted in Western academic thought, which has long been centred around a Eurocentric, colonial worldview. This worldview is so deeply embedded within our professional practice that it is almost invisible to those who are not directly oppressed by it, but the resulting absence, misrepresentation, and marginalisation of indigenous voices in our heritage institutions is a form of violence through historical erasure.’

Megowan identifies library special collections as a ‘resource to be challenged, interrogated and complicated’. The Devon and Exeter Institution is well-placed to foster dialogue and debate and to encourage diverse responses to collections – ‘whether creative, personal, informal or academic’. We are already encouraging the next generation of potential heritage custodians to seek out hidden colonial histories through Global Lives, a collaborative module with our partners at the University of Exeter, now in its fourth year. And we will be exploring more hidden histories in the collection in partnership as part of our project, ‘The Next Chapter’.

Emma Laws, Director of Collections and Research

The full text of Clapperton’s first expedition in northern and central Africa, narrated by Dixon Denham, can be read online here.

The full text of Clapperton’s Journal of a second expedition into the interior of Africa, from the Bight of Benin to Soccatoo is available online here.