Spring has sprung

Spring has arrived in the Institution garden inspiring us to look through our collections...

Spring has sprung in the DEI garden and, like many of us, the bulbs seem to be benefiting from the signs of better weather. A particularly welcome sight has been the flowering of our first primroses (Primula Vulgaris) of the year. Their cream and yellow petals make the plants a firm and familiar favourite with many of our members today, but we do not need to look far into the collections to see that the primrose has a long and curious history, with some particularly interesting Devon connections!

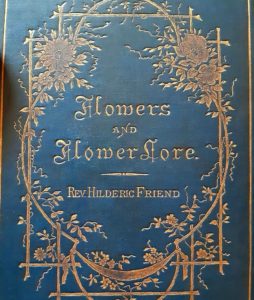

In the 1880s, when the Institution was still relatively young, an interest in flowers, flower lore, and flower language emerged. In the DEI collections we have several volumes which attest to the interest in these pursuits. Two volumes, Reverend Hilderic Friend’s 1886 Flowers and Flower Lore and T. F. Thiselton-Dyer’s 1889 The Folklore of Plants provide extensive discussion of the primrose, its properties, and the fables connected with the plant. Both discuss the Devonshire-based idea that taking a single bloom of the primrose into any house will cause the interaction to be ill-fated, with Thiselton-Dyer in particular reflecting “one should never take less than a handful of primroses or violets into a farmer’s house, as neglect of this rule is said to affect the success of the ducklings and chickens.” He also discusses their potentially prophetic properties, and the tendency for young women to use the flowers as love charms.

In the 1880s, when the Institution was still relatively young, an interest in flowers, flower lore, and flower language emerged. In the DEI collections we have several volumes which attest to the interest in these pursuits. Two volumes, Reverend Hilderic Friend’s 1886 Flowers and Flower Lore and T. F. Thiselton-Dyer’s 1889 The Folklore of Plants provide extensive discussion of the primrose, its properties, and the fables connected with the plant. Both discuss the Devonshire-based idea that taking a single bloom of the primrose into any house will cause the interaction to be ill-fated, with Thiselton-Dyer in particular reflecting “one should never take less than a handful of primroses or violets into a farmer’s house, as neglect of this rule is said to affect the success of the ducklings and chickens.” He also discusses their potentially prophetic properties, and the tendency for young women to use the flowers as love charms.

Meanwhile Friend, more widely, discusses the connection of the primrose with early youth, and reflects “sadness and even Death itself have been associated with this pretty flower.” Friend also notes the contemporary celebration “Primrose Day,” created in 1881, to honour the late Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. Disraeli was said to have loved the flowers so much that Queen Victoria regularly sent him bunches of the blooms from Windsor and Osborne House. As is the case at many points throughout Friend’s and Thiselton-Dyer’s texts, the ephemerality and brevity of life is reflected on through the fragile beauty of the Primrose. Friend observes:

“Ladies will wear primroses in their head-dresses, and gentlemen sport them in button-holes, and wreaths will still be consecrated at the Earl’s shrine, when our heads are laid in the dust, and when the real meaning of the custom is forgotten.”

However, a note of hope and perseverance is also conveyed in the symbol the primrose. It must be noted, after all, that despite its fragile appearance, the Primrose is rather a hardy plant, which blooms and lasts throughout the early Spring. Perhaps most intriguingly, when five flowers appear in one rosette, the Primrose is said to mark the gateway to the land of the fae. A smaller cluster is still supposed to serve as a home for fairies, who might seen dancing across the petals by a particularly keen observer (whether the fairies are in actual fact the wings of a Duke of Burgundy butterfly, or bee-flies, who both feed from the plant, is yet to be firmly established). Either way, next time you come across a primrose, either in our garden, or elsewhere, take a look at this remarkable plant up close. At the centre of the bunch, protected by its famously wrinkled bulky green leaves, is a single, surprisingly short stem. It may be that the Primrose’s true tiny nature, hidden beneath its protective leafy bulk, has created its mythology. When we reconsider the Primrose’s physicality, it seems less surprising that this Spring bloom has functioned as symbol of a young life cut short, immortalised in the beauty of the faery world.