Samuel Parkes’s Chemical Catechism (1806)

While working as a soap manufacturer in Stoke-on-Trent, Samuel Parkes (1761-1825) became fascinated in chemistry. A Chemical Catechism (1806), originally written for his young daughter, became a best-seller across Europe. His method of teaching stressed the importance of observation – but we don't recommend trying his 'amusing experiments' at home!

Samuel Parkes was self-taught. He began his career in his father’s grocery business in Stourbridge and in 1793 moved to Stoke-on-Trent to work as a soap manufacturer. Keen to improve his product, Parkes began to study chemistry and apply it to his work:

If we look to the manufactures of the kingdom, there is scarcely one of any consequence that does not depend upon chemistry, for its establishment, its improvement, or for its successful and beneficial practice.

By 1803 he had settled in London as a manufacturing chemist.

Parkes married on 23 September 1794; his daughter, Sarah, was born three years later. When Sarah was about nine years old, Parkes produced a series of chemistry lessons for her in manuscript form. These were published in 1806 as A Chemical Catechism for the use of young people: with copious notes for the assistance of the teacher. The book went through thirteen English editions, numerous American editions and was translated into French, German, Spanish and Italian. It even reached the Emperor of Russia who, it is said, sent him a valuable ring in return. Parkes published further works, including The Rudiments of Chemistry (1809) – an abridged version of his Chemical Catechism for use in schools – and Chemical Essays (1815), a five-volume work.

Parkes advocated the study of chemistry for its ‘habit of investigation’. Chemistry, he believed, ‘lays the foundation of an ardent and inquiring mind’, whatever a child may grow up to do. He also believed in encouraging a ‘love of knowledge’; the catechetical form was not intended to be rigid or to be ‘committed to memory verbatim by the pupil’. Instead, ‘whether it be employed as a catechism, as a set of dialogues, as matter for familiar conversation, or as a book for the closet’, Parkes hoped to encourage students to undertake self-study and develop a passion for the subject.

What is water?

Water is a compound consisting of hydrogen and oxygen.

In how many states do we find water?

In four: solid or ice; liquid or water; vapour or steam; and in a state of composition with other bodies.

Which is the most simple state of water?

That of ice.

What is the essential difference between liquid water and ice?

Water contains a larger portion of caloric.

How do you define vapour?

Vapour is water, combined with a still greater quantity of caloric.

What are the properties of vapour?

Vapour, owing to the large quantity of caloric which is combined with it, takes a gaseous form, acquires great expansive force, and a capability of supporting enormous weights; whence it has become a useful and powerful agent for raising water from deep pits, and for other important purposes.

In which properties are oxygen and hydrogen in water?

Water is composed of 85 parts by weight of oxygen, and 15 of hydrogen, in every 100 parts of the fluid.

Samuel Parkes presented his book to parents as ‘a body of incontrovertible evidence of the wisdom and beneficence of the Deity’ and made no apology for including ‘moral reflections’ that might seem ‘irrelevant to chemical science’ but which he believed might defend young readers ‘against immorality, irreligion, and scepticism’. No doubt, such remarks derived from his strong Unitarian faith, but probably also served as a clever marketing ploy. Parkes also softened the text and broadened its appeal with numerous excerpts of poetry by the likes of James Thomson, William Falconer, William Hayley, Mark Akenside and Erasmus Darwin; art, science and commerce were inextricably connected in Parkes’ enlightened view of the world.

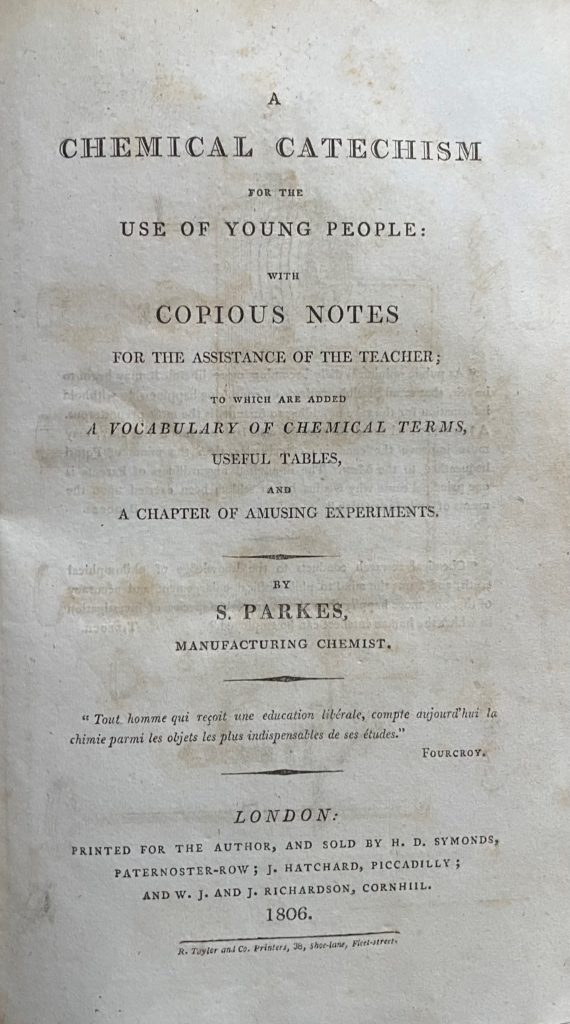

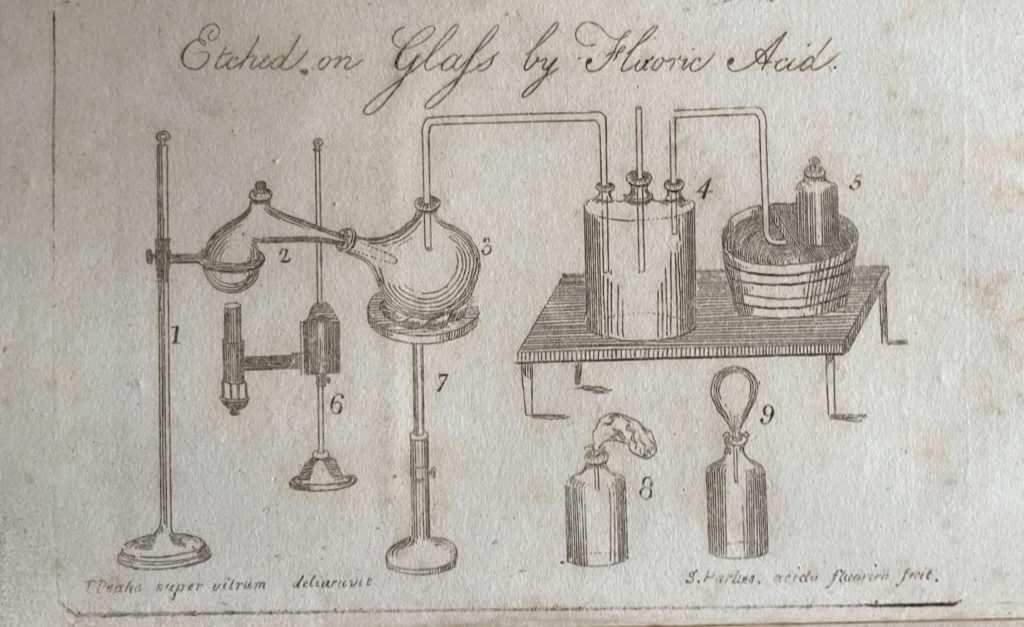

Following the chapters on air, heat, water, earths, alkalies, acids, salts, combustibles, metals and oxides, Parkes provides ‘a chapter of amusing experiments’, describing the methods but leaving the student to ‘discover the cause of every effect …’:

‘Nothing tends to imprint chemical facts upon the mind so much as the exhibition of interesting experiments. With this view the following selection has been made, in which such experiments as may be performed with ease and safety, have uniformly been preferred….’

A sample of Parkes’ ‘striking experiments’:

Fix a small piece of solid phosphorus in a quill, and write with it upon paper. If the paper be now carried into a dark room, the writing will be BEAUTIFULLY LUMINOUS.

Procure a bladder furnished with a stop-clock, fill it with hydrogen gas, and then adapt a tobacco-pipe to it. By dipping the bowl of the pipe into a lather of soap, and pressing the bladder, the soap-bubbles will be formed, filled with hydrogen gas. These bubbles will rise into the atmosphere, as they are formed, and convey a good idea of the principle upon which AIR-BALLOONS are inflated.

Pour a little pure water into a small glass tumbler, and put one or two small pieces of phosphuret of lime into it. In a short time FLASHES OF FIRE will dart from the surface of the water, and terminate in ringlets of smoke, which will ascend in regular succession.

Put thirty grains of phosphorus into a Florence flask with three or four ounces of water. Place the vessel over a lamp, and give it a boiling heat. Balls of fire will soon be seen to issue from the water, after the manner of an artificial fire-work, attended with the most beautiful corruscations [sic]. An experiment to show the extreme INFLAMMABILITY OF PHOSPHORUS.

Emma Laws, Director of Collections and Research

You can read the full text of A Chemical Catechism here.