Oyntments, powders and syrops – a mysterious medical recipe manuscript

Medical recipe manuscript. Classmark: MSS 17

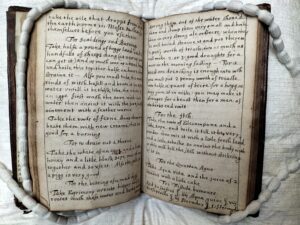

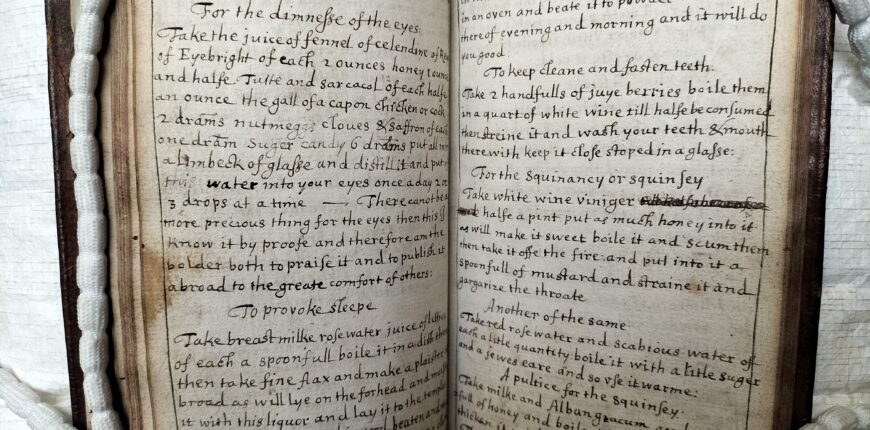

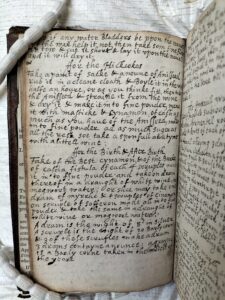

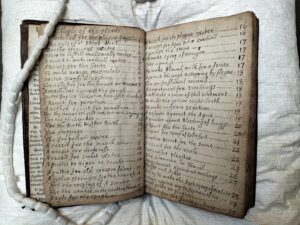

Deep in the Manuscripts Cupboard of the Devon and Exeter Institution lives a small, roughly bound, handwritten book, containing recipes for the treatment of many ailments, from ‘almond milk for a fever’, to ‘a powder against bleeding of lunggs’ and ‘an ointment against swellings’. There are even instructions to make ‘a distilled water for the plague’. This manuscript contains no clear indications of authorship, although the recipes appear to date from the mid seventeenth century through to the nineteenth century. Written in different hands, there is the suggestion of this book being passed down, sharing its medicinal wisdom through the generations.

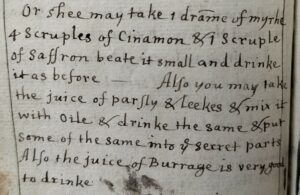

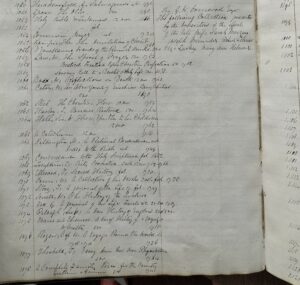

The recipes are often complex, with calls for numerous ingredients, both rare and commonplace. Spices such as cinnamon, ginger and nutmeg feature highly, as does ash, tobacco and beer. Some require many days work to create, to allow for infusion, or ‘the vertue of the herbe be drawne’. Measurements consist of ‘scruples’, ‘drames’, ‘handfulls’, and often monetary figures, such as ‘2 penny worth of triacle’. A great deal of care has been taken in the compilation; the writing is neat and clear, the pages numbered, and each recipe dutifully recorded in the contents page, or ‘table of the heads’. This was evidently a volume of great importance to its owners.

Although no other copies of this particular book exist, early modern medical manuscripts are not uncommon, and offer an insight into the medical work carried out by women, excluded from the professional sphere but active in their own homes and local areas. There are hundreds of books of this type in the Wellcome Collection alone. Former curator of western manuscripts, Richard Aspin, describes how ‘manuscript recipe books were at the forefront of Henry Wellcome’s collecting activities’, but fell out of fashion from the 1930s to the 1980s, when there was ‘no obvious scholarly interest in the history of domestic medicine’.

So how did this particular manuscript make its way onto the DEI shelves? A bookplate pasted into the front cover tells us that it was transferred from the collections of Sarah Morgan upon her death in 1865, although there are no clues as to whether she added to the book. Articles appeared in both the Western Times and the Exeter Flying Post shortly after she passed away, telling us that she died intestate, and that she had been a member of the Society of Friends. Quaker registers of birth show that Sarah was born in Exeter in 1784, to Sarah and Samuel Morgan, who is listed as a linen draper on his burial record. Alongside this volume, the inheritors of her effects deposited a large number of books with the DEI, as noted in the donation records.

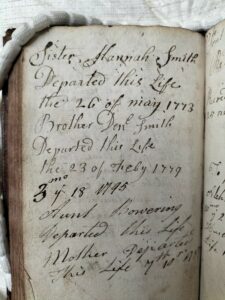

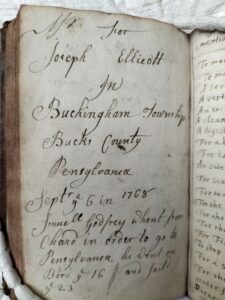

Additional clues as to the identities of the authors can be found inside the pages, although it is unclear how these individuals relate to Sarah Morgan, or how the book ended up in her possession. There are notes towards the back of the book, seemingly added by one of the later contributors, recording the deaths of their close relations. There appear to be links to Quakerism here too; ‘Aunt Bowering’ who passed away on the 3 March 1795 is likely to be Susannah Bowring whose death on the same date is recorded in a Quaker burial register for the Bristol area. In Susan H. Bradt’s recent study, Women healers, she reported the ‘Friends’ emphasis on female literacy and spiritual equality allowed Quaker women to enter the public sphere to a greater degree than their non-Quaker counterparts’ and identifies a number of manuscript recipe books created by them, both in Britain and the American colonies.

Bradt reports that the stereotypical picture of an early modern female healer usually fell into one of two camps: either the elite woman, literate and skilled in her healing practices, or old wives, or village wise women, with negative associations of cunning, ‘outsiderness’ and witchcraft. Like Bradt, Amanda Herbert, in her work Female alliances: gender, identity, and friendship in early modern Britain, shows that although medical recipes were ‘ostensibly composed by elite women of the period’ there was in fact a great deal of cooperation between ‘women of many diverse ranks, ages, and educational backgrounds’. Some of the early entries record the origins of the recipes, one ‘given by Dr Martyn’ and another ‘from my Ladie Martyn’. The required ingredients in the book suggest an owner of reasonable means, and either the time needed to follow the recipes, or the ability to pay somebody else to do it.

In many ways the book raises more questions than it answers, and the mystery is undoubtedly part of its charm. We invite researchers to delve deeper into its secrets, drawing them out much as ‘the gall of a pigg’ draws out a thorn.