John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera

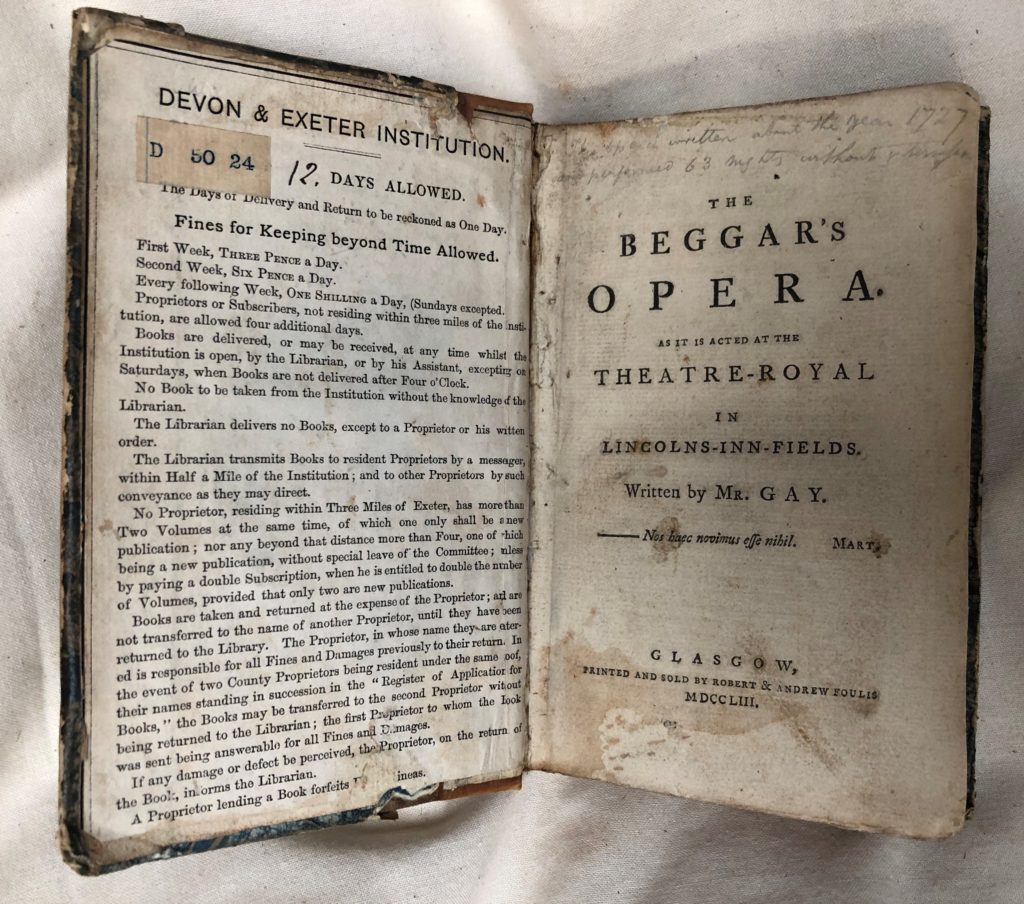

Originally from Barnstaple in Devon, John Gay (1685-1732) became one of London’s most renowned dramatists. His satirical ballad opera, The Beggar’s Opera, opened at Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre on 29 January 1728 and ran for 62 nights. Gay’s assault on the topsy-turvy morals, double-standards and self-interests of 18th century politics and aristocratic society remains one of the few 18th century plays still performed today.

John Gay belonged to the Scriblerus Club – a coalition of like-minded anti-Enlightenment novelists, poets, playwrights and politicians who railed against the vanities of modern intellectual life and culture in the early 18th century. Founded in 1714 out of the coffee-house culture, the club included Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, John Arbuthnot and Thomas Parnell. John Gay was almost certainly influenced by his close friends Pope and Swift; with its cast of crooks and con artists, The Beggar’s Opera is a satire on the pretensions, self-interests and double standards of 18th century society – and a jolly good romp to boot.

‘Through the whole piece you may observe such a similitude of manners in high and low life, that it is difficult to determine whether (in the fashionable vices) the fine Gentlemen imitate the Gentlemen of the Road, or the Gentlemen of the Road the fine Gentlemen.’

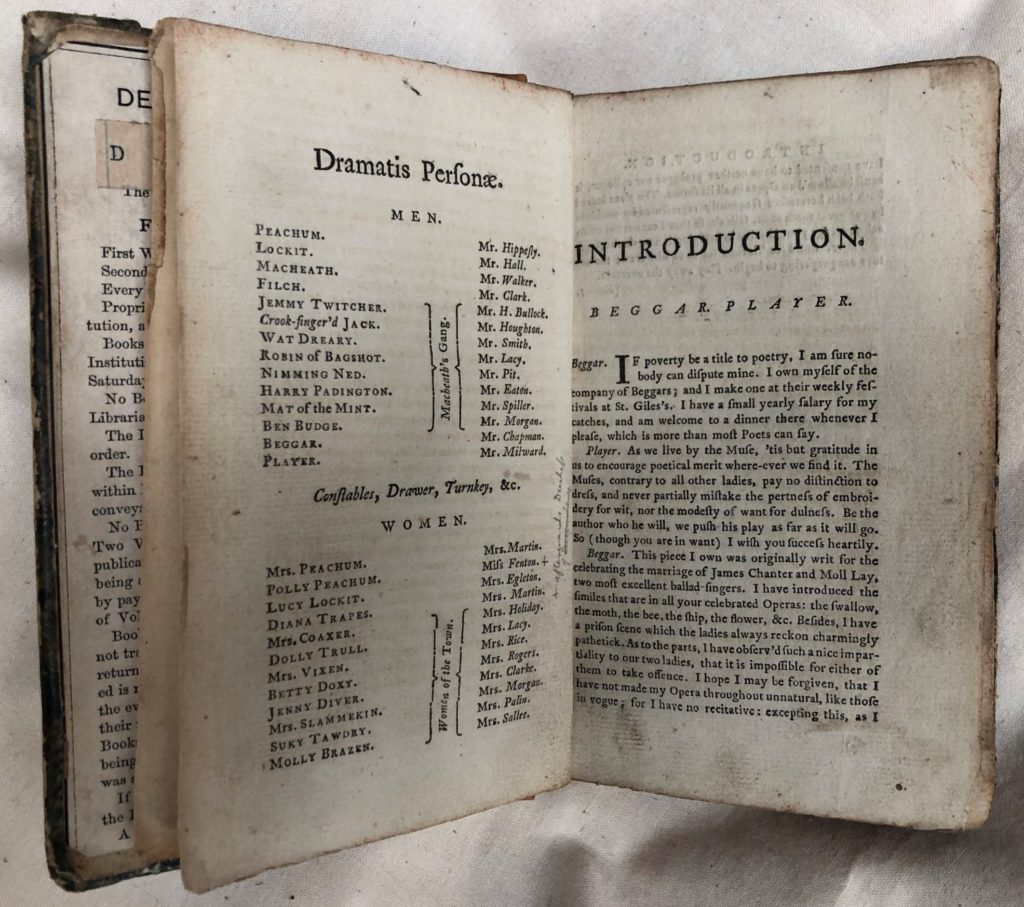

Peachum, a caricature of Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole, runs a gang of thieves, highwaymen and prostitutes and profits from their takings. He can ‘forgive as well as resent’ as it suits him; when the criminals are no longer of use to him, he turns them in to the authorities in return for financial rewards. (Peaching is slang for informing.)

Gay drew inspiration for the character of Peachum from the infamous real-life criminal, Jonathan Wild, who mastered a gang of thieves and outlaws and then betrayed them one by one to the legal system for pay-outs; over a hundred criminals were hanged based on his evidence. Wild got his comeuppance in 1725 when he was publicly hanged; tickets for the best seats at the event quickly sold out.

Gay attacks what he sees as the double standards of the legal profession of his day: ‘The lawyers … don’t care that any body should get a clandestine livelihood but themselves’. Indeed, in his own mind, Peachum is no different to the lawyers who profit from criminal activity:

‘A lawyer is an honest employment, so is mine. Like me too he acts in a double capacity, both against rogues and for ‘em; for ‘tis but fitting that we should protect and encourage cheats, since we live by ‘em.’

Gay’s bourgeois audience would have nodded in agreement when another character, Ben Budge, declares, ‘We are for a just partition of the world, for every man hath a right to enjoy life’. Peachum is a sort of Robin Hood character, stealing from the rich and distributing the wealth to those who will use it rather than hoard it:

‘We retrench the superfluities of mankind. The world is avaritious, and I hate avarice. A covetous fellow, like a jack-daw, steals what he was never made to enjoy, for the sake of hiding it. These are the robbers of mankind, for money was made for the free-hearted and generous, and where is the injury of taking from another, what he hath no heart to make use of?’

Captain Macheath is one of Peachum’s most successful criminals. However, Peachum’s plans begin to go awry when his daughter, Polly, falls in love with Macheath and secretly marries him. Peachum decides to impeach Macheath and have him hanged. He captures Macheath and imprisons him in Newgate prison under the watchful eye of his business partner, Lockit, the jailer. Macheath is set free by Lockit’s daughter, Lucy, who also falls in love with him, but he is soon captured again. In the final act, Macheath is pardoned and chooses Polly as his one true wife.

In The Beggar’s Opera, Gay mocks the conventions of the Italian operas that were popular among the aristocracy of his day. In the penultimate scene of the play, the commentators, the Beggar and Player, discuss the ending. The Beggar suggests that to ‘make the piece perfect’, Macheath should be hanged; the Player replies, ‘Why then, Friend, this is a down-right deep Tragedy. The catastrophe is manifestly wrong, for an opera must end happily … to comply with the Taste of the Town’. They agree to write an incongruously happy ending.

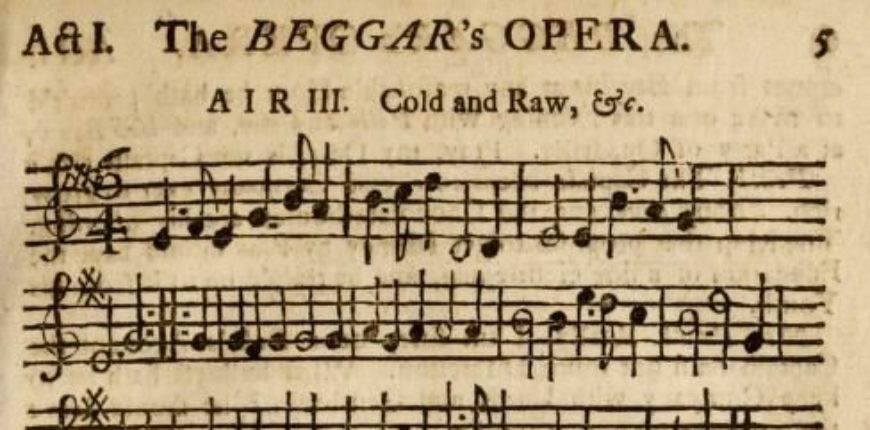

Gay’s play is a ballad opera – a popular 18th century genre that fuses traditional opera with broadsheet ballads of the street to tell the stories of the lives of ordinary people. The scenes are short and punctuated with sixty-nine rousing songs, most of which will have been familiar to the audience. The copy at the Devon and Exeter Institution is missing some preliminary pages which probably listed the names of the songs – a mixture of folk songs, well-known airs and even nursery rhymes.

Gay wrote a sequel to The Beggar’s Opera recounting the adventures of Polly Peachum, now removed to the West Indies. The Lord Chamberlain refused to allow the play to be produced but Gay published it anyway in 1729, by subscription, and made thousands of pounds, proving that all publicity is good publicity.

The full-text of The Beggar’s Opera is available online here.

Emma Laws, Director of Collections and Research