An intricate and arduous undertaking: George Montagu (1753-1815) and his collection of shells

Beautiful, intricate and varied, shells have adorned our clothes, our homes and our objects of art for centuries. From the end of the 17th century, natural scientists began to collect, organise, observe and draw them in earnest. George Montagu’s Testacea Britannica (1803) is one of the most important works of natural history to come out of the Age of Enlightenment – and it has a special significance for Exeter.

Searching for shells on a sandy beach in the summer remains a rite of passage in many childhoods. Today we know that removing shells and other ‘treasures’ from beaches can damage vulnerable ecosystems but in years past children have taken shells home to paint, glue into collages, press into rock gardens and keep in treasure boxes and glass bottles.

Shells are endlessly fascinating. An ancient pastime, shell collecting became increasingly popular from the late 18th century; explorations to far-off countries were opportunities to study and bring back curious and exotic specimens and by the mid-19th century shells were fetching high prices in auctions. The London Evening Standard reported a ‘very heavy interest’ in the shells at an auction on 12 November 1879: ‘a good demand prevailed, and prices ranged generally higher’. On 12 January 1861, George C. Hyndman, a Belfast auctioneer, sold ‘a collection of foreign shells, containing several fine specimens from the Indian Islands, South America, and other places.’

Decorative shellwork first appeared in the 17th century on boxes and caskets. By the 18th century, shells were familiar motifs in Rococo ornament and featured on everything from elaborate ceilings to ornate gilt mirrors. Grottos and shell-houses, decorated with hundreds of shells, became highly fashionable. In 1808, the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser described a London tea garden as ‘finished in a true style of elegance and neatness’ and ‘enriched with a grotto and tea-room of shell-work’. Towards the end of the 19th century, Mary and Jane Parminter collected shells and semi-precious stones on their European Grand Tour and displayed them in a cabinet of curiosities in their Devon home at A La Ronde, Lympstone; the shell gallery, decorated with over 25,000 shells, is probably their own handiwork.

Indeed, shellwork became a popular craft among women. The Ipswich Journal advertised the opening of a Young Ladies School in Yarmouth in August 1788: ‘where they may be taught the following branches of useful and elegant education … plain needle-point, cloth work, turkey work … tent work, embroidery and shell-work’. In Dublin, Mrs Seagrove advertised her ‘universally approved’ plan of education in the Dublin Evening Post on 20 January 1785, including a catalogue of fashionable pursuits:

…all sorts of needle-work and the fine works taught in the nunneries on the continent, tapestry, Dresden, embroidery, tambour, artificial flowers, white-paper work, grotto and shell-work; painting on gauze, crape and ribbon-work, &c. … Particular attention will be paid to inculcate a becoming affability and easy politeness; a neatness in dress, and the most graceful carriage and deportment.

For many in the 18th century, the intricacy and beauty of the natural world pointed to the existence of a creator God.

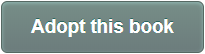

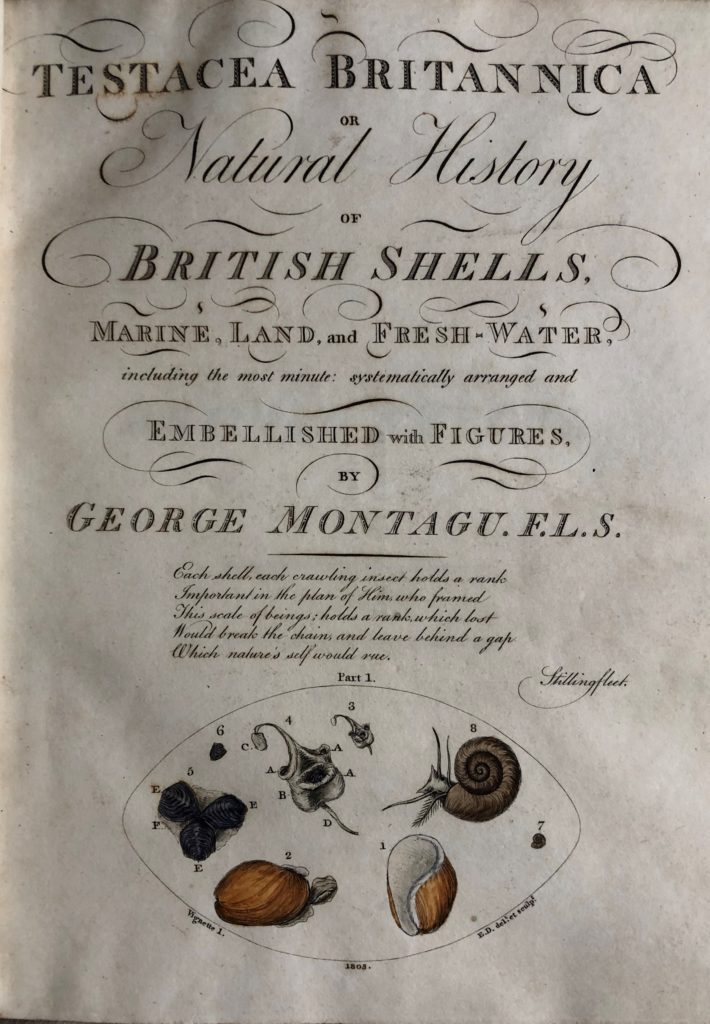

Mary Delaney (1700-1778), a prominent shell artist, declared, ‘the beauty of shells is as infinite as flowers, and to consider how they are inhabited enlarges a field of wonder that leads one insensibly to the great Director and author of these works’. George Montagu (1753-1815) expresses a similar sentiment in his introduction to Testacea Britannica: a Natural History of British Shells, Marine, Land, and Fresh-water (1803):

‘In the present age, it is acknowledged, that every link in the great chain of nature is important, the study of which may tend not only to the comforts and luxuries of life, but to the love, adoration, and, admiration of that being, who alone was capable of forming the whole.’

The work of the Swedish botanist, Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), prompted a surge of amateur and professional interest in natural history. A member of the Linnaean Society, George Montagu applauded Linnaeus and his contemporaries for dispelling the ‘days of darkness’ when ‘the researches of the naturalist were considered as trivial and uninteresting’. While Linnaeus had not considered the study of shells ‘worthy his notice’, Montagu remarked that since ‘their extreme beauty, and variety, naturally attracted attention, and their durability enabled them to be preserved without trouble, no branch of natural history has been more sought after’.

George Montagu is best-known for his Ornithological Dictionary or, Alphabetical Synopsis of British Birds (1802); his private collection of British birds was purchased by the British Museum in 1816. He amassed a collection of shells, too, many from the West Country, especially Salcombe harbour:

‘At Salcombe on the coast of South Devon, [the Pholas Dactylus] is found in great abundance together with the P. Candidus and Parvus burrowed in the stumps of old trees, which formerly grew there, but now covered with the tide except at very low water. These are taken by the fishermen and used with success for baiting their hooks’.

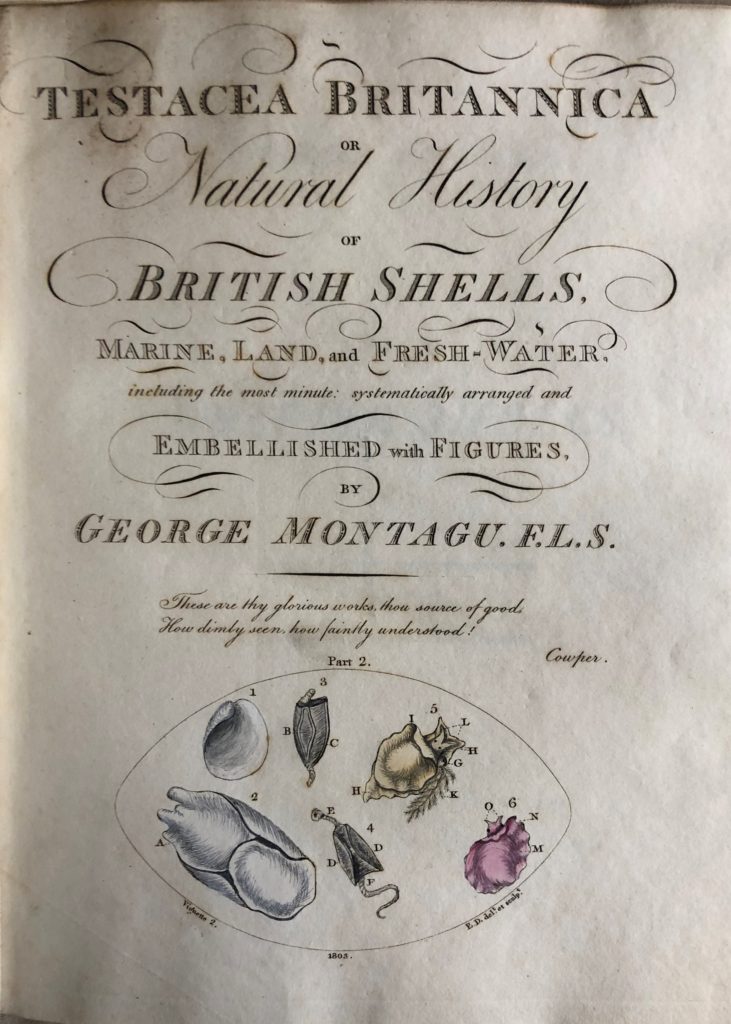

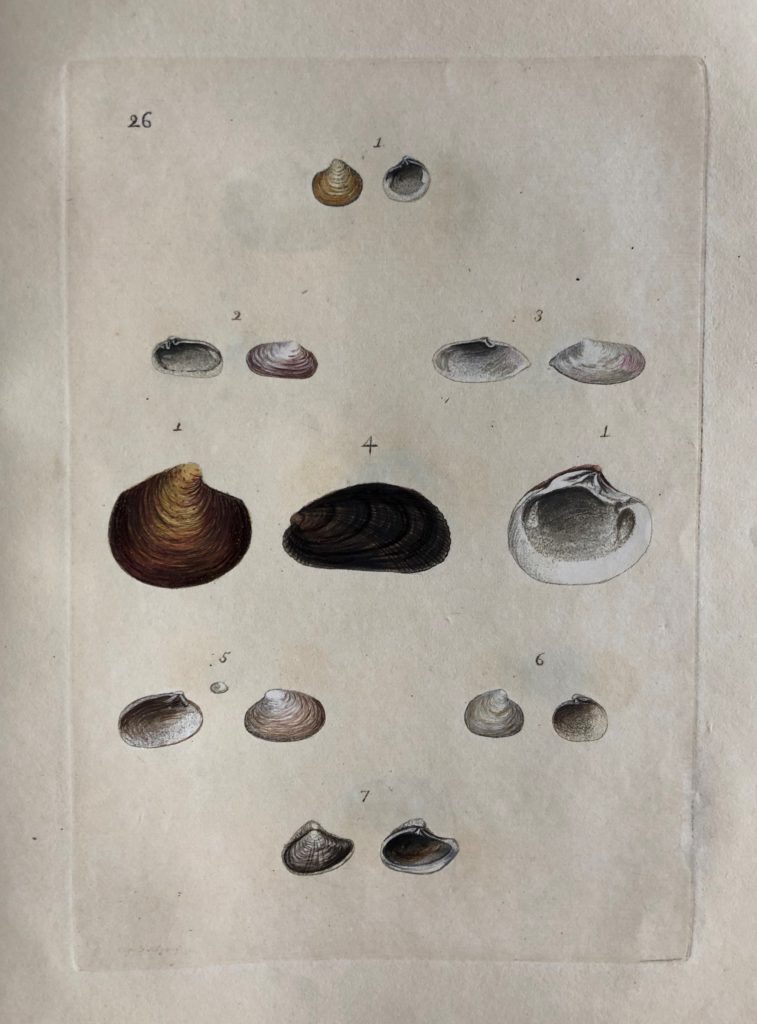

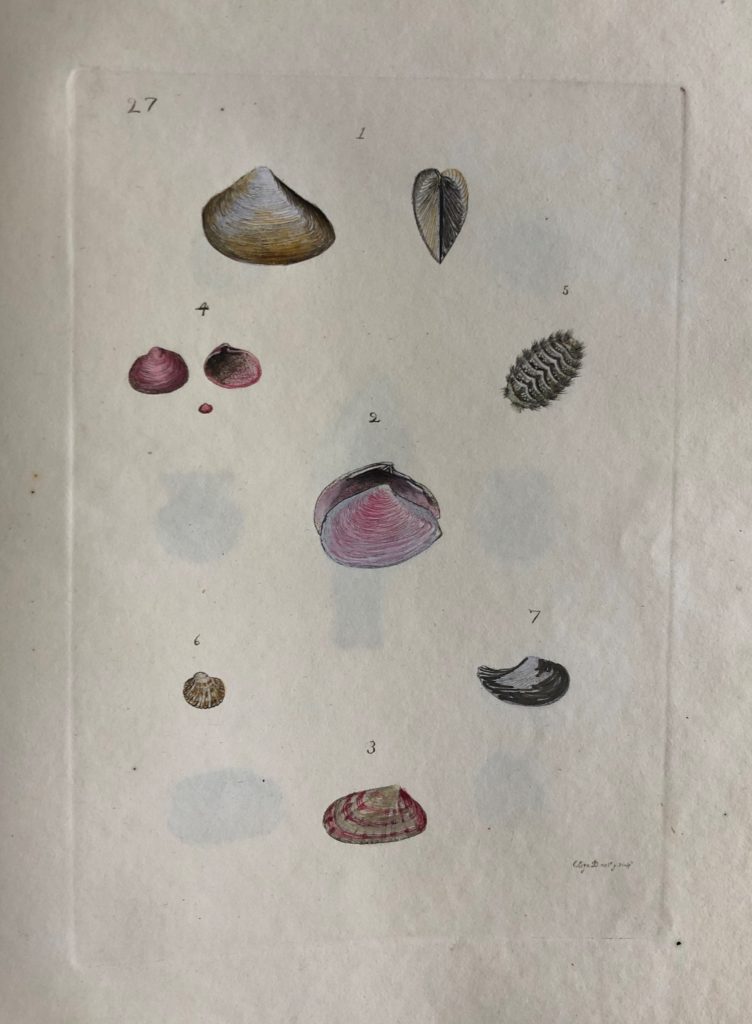

With a few exceptions, the numerous shells described in Testacea Britannica were from his own cabinet, ‘collected from their native places by ourselves, or by the hands of a few friends’. He identified many ‘which have never been described as English, and some entirely new’, often using a microscope to study minute details.

His work, ‘so intricate, and arduous an undertaking’, was published in December 1803 and ‘handsomely printed in quarto, price two guineas, or on a fine wove paper, with the plates accurately coloured, price four guineas, in boards’.

Montagu does not name the ‘feminine hand of the engraver’ – his mistress, Mrs Elizabeth D’Orville – but he goes to great lengths to forestall any criticism of her work:

‘Should the following sheets be deemed to possess any small share of merit, the public are indebted to the labours of a friend, who not only undertook the engraving, but in part also the colouring of the figures; executed from the objects themselves, they are a faithful representation, unadorned with the gaudy, high-coloured tints, which too often mislead. But for this assistance, so necessary in the smaller species, this work might never have seen the light … As this friend of science, however, may not undeservedly feel the shafts of the critical artist, it may be right to disarm them, by observing that, the feminine hand of the engraver was self taught, and claims no other merit in the execution, than what results from a desire to further science by a correct representation of the original drawings, taken by the same hand…

At the age of 20, Montagu had eloped to Scotland with Ann Courtenay, the eldest daughter of William Courtenay and Lady Jane Stuart. They settled at Alderton House in Wiltshire and had a son and three daughters. However, around 1789 or 1790 he met and began an affair with Elizabeth D’Orville; by 1800 he had left (though not divorced) his wife and was living happily with Elizabeth at Knowle House near Kingsbridge in Devon. In his will Montagu provided for his wife, Ann, but also for Elizabeth to whom he left his most treasured belongings:

‘my library of books, collections of natural history cabinets, manuscript publications and copyrights thereof also coins, plate, jewels, rings, watches, household furniture … as an acknowledgement for the very great assistance she has given me in my pursuits of natural history’.

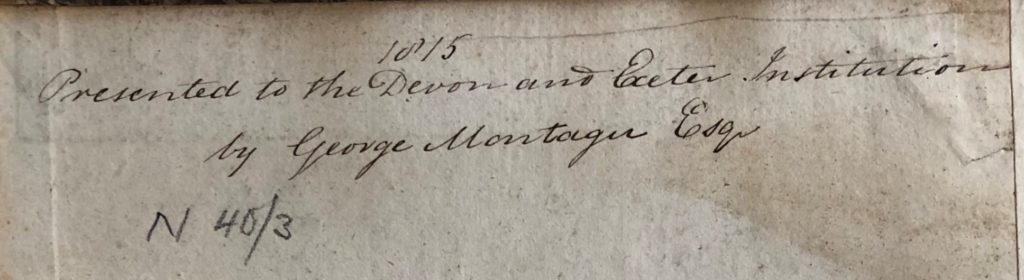

The year he died, Montagu gave copies of his Ornithological Dictionary and Testacea Britannica to the science collection at the new Devon and Exeter Institution; his donations are recorded within the books, possibly by the Institution’s first librarian, John Squance. Montagu left his remarkable collection of shells to his son, Henry D’Orville, who subsequently gave it to the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter in November 1874. In January 2020 Arts Council England awarded the collection Designation status as a reflection of its international importance to science.

The full text of George Montagu’s Testacea Britannica is available online here.

While the RAMM is closed in line with advice from Public Health England, you can visit the Museum’s website for more information on the life of George Montagu and to view the illustrated catalogue of his collection of shells.

Emma Laws, Director of Collections and Research