Charlotte Chanter’s “Ferny Combes” and the fashioning of the fern craze in Devon

“My humble effort is designed to lead the youthful and cheer the weary spirit, by leading them, with a woman’s hand, to the Ferny Combes and Dells of Devon.”

Beautifully illustrated with botanical drawings and sketches of local spaces, this enchanting guide to collecting and identifying the “ferns of Devonshire” is a testament to the late Victorian “fern craze” or “pteridomania,” written by the Clovelly-born writer Charlotte Chanter.

As she “rambles” through Combmarten, Ilfracombe, Woolacombe, and Welcomb, Chanter draws on the traditional word “Comb” to describe a “hollow or valley on the flank of a cliff,” or a “steep short valley running up from the sea coast,” playing upon the idiosyncrasies of South-Western terminology as she refers to the names of the towns themselves. Taking up the idea of the “hollow”, Chanter challenges her readers to engage in close observation, to make an active and sustained pursuit of hidden spaces in order to make real “discoveries” of note. The “study of ferns,” Chanter insists, “leads the collector into the most picturesque scenery and the wildest haunts of nature.” Nonetheless, a “young botanist” should “never name a fern unless it is seeded, as many leaves of flowering plants greatly resemble some ferns in their outline and cutting.” The sense was, that even by 1857, much of the work to taxonomize these newly-popular plants had already been accomplished, and that to obtain a true find, the enthusiast had to be committed to plumbing hidden places and “untrodden corners.”

The good news, however, was that in terms of explored ground, Devonshire, the locus of Chanter’s guide, was only really just coming into its own. The South Devon Railway, enabling quicker and more affordable travel for tourists to the Jurassic coast, had been completed in 1849, and guides such as Murray’s Hand-book for Travellers in Devon & Cornwall, published in 1851, supported and attested to the interest in journeying to Britain’s remoter areas. The 1850s truly saw the birth of the local holiday, and amongst the holidaymakers, invested individuals collected fossils, seaweed, or “took the sea air” along South-Western shorelines. Consequently, Chanter makes sure to foreground the picturesque qualities of “Beautiful Devonshire,” as the tourist “rush[es] towards” the county “on the railway.” However, she simultaneously encourages her readers to look beyond the obvious, to walk with her beyond the end of the “beaten” railway track, towards the charms of her native Clovelly:

“The Combes of North Devon, with one or two exceptions, are rarely above two or three miles long; and if we could take a bird’s-eye view of the country, we should see that the land within three or four miles of the sea is irregularly scored with these glens, the sides of which, when cultivated, prove rich and fertile; but for the most part they are poorly farmed, or still covered with a tangled mass of briar, ferns and golden gorse.”

Finding the beauty and the treasures in the “tangled” wilderness, the “poorly-farmed” and less-cultivated land, Chanter attests to the particular qualities and suitabilities of rural Devon to the dedicated fern collector. The specific attributes, conditions and untouched “nature” of the space are integral to the enthusiast’s success. If they promise to leave their “dignity behind” and climb the cliffs and hunt in the hollows, Chanter suggests, they will be amply rewarded:

“…it is no exercise of observation to walk straight to a given point, pluck a leaf, and walk back again ; no, a fern collector, if he really wish to make discoveries, must ever be on the alert, ever watching: even on a wall you have passed a hundred times without observing anything curious, the hundred and first time you may find a treasure you did not think was within fifty miles of you.”

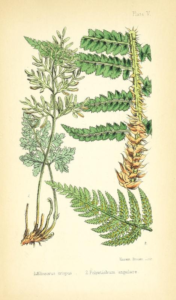

Plate V, “Allosorus Crispus; Polystichum angulare”, Ferny Combes: A Ramble after Ferns in the Glens and Valleys of Devonshire, 3rd edition, by Charlotte Chanter, (Lovell Reeve, 1857), 57.

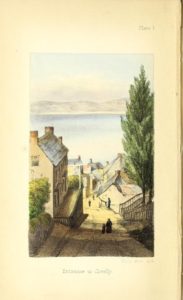

Fern-collecting is clearly presented as difficult pursuit with tangible rewards. In describing such discoveries as “treasures,” indeed, Chanter was not alone in appreciating the ornamental qualities of fern leaves. Finding decorative potential in the fronds and furls of the plants, many collectors pressed their finds into books and albums, whilst ferns appeared in stylized forms on dresses, in typography, and even on biscuits (the 1908 invention of the custard cream being one still extant example). Similarly, readers of Chanter’s guide would also certainly have taken delight in the visual qualities of her volume. The tinted illustrations of ferns, carefully dispersed throughout her text, served to inform and please the eye at once. The depictions of Devon, idyllic, calm, and non-industrial, contributed to a similar sort of aestheticization. Devonshire and its ferns are brought to enchant the urban reader through the new possibilities of modern print, and to entice them to the area.

The irony, of course, was that in encouraging the tourist to plumb the hollows for hidden treasures, Chanter was herself contributing to the commercialisation of the space. As she leads the tourist, “with a woman’s hand, to the Ferny Combes and Dells of Devon,” she presents herself as a faery-like guide, drawing upon the tradition of associating ferns with the realms of the fae. (Even in 1847, Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, described as a figure of fantasy by her beloved Mr Rochester, ends up dwelling at the conveniently-named Ferndean Manor at the end of the novel, in a fairytale-like ending). Chanter, indeed, is sure to include folk tales of wanderers getting lost in the evening fog, or losing their footing between the ancient oaks of Wistman’s Wood. The implication is, that despite her pretensions to humility- Charlotte insisted “I must disclaim any intention of attempting to supersede those scientific and necessary works already published on the Study of Ferns”- the traveller to Devon would be lost without her guide. The varieties of Devonshire ferns, decorative, enchanting, and, in 1857, still mysterious, (Chanter herself admits to being unable to find one particularly-desired specimen), are caught and marketed by this young writer in a timely and clever fashion. Finally, she encourages her reader, after leaving Devon, to purchase a glass case to keep their own live specimens, and keep a “miniature greenhouse.” In 1855, Chanter’s brother, the novelist Charles Kingsley, had coined the term “Pteridomania,” to describe contemporary Fern Fever. By 1857, within a year of writing her original guide, Chanter’s volume inspired two subsequent editions, with increased amounts of illustrations. Charlotte Chanter had firmly directed the fern collectors to the Combes of Devon.

Plate I, “Entrance to Clovelly,” frontispiece, Ferny Combes: A Ramble after Ferns in the Glens and Valleys of Devonshire, 3rd edition, by Charlotte Chanter, (Lovell Reeve, 1857).