Bowdler’s defence of single women

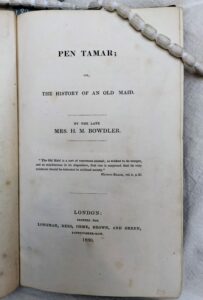

H. M. Bowdler, 'Pen Tamar', (1830). Classmark: S.W. Heritage 1830 BOW

In her novel set during the tumultuous seventeenth century, Henrietta Maria [Harriet] Bowdler (1750-1830) sought to defend the respectability of unmarried women against the prejudice and ridicule of the age. She is now best known for The Family Shakespeare in which she expurgated the bard’s work of ‘every thing that could give just offence to the religious and virtuous mind’, namely references to sex and Roman Catholicism. It was her brother who took credit for this work, although Harriet gained literary notoriety through the publication of other popular works, such as Sermons on the doctrines and duties of Christianity, which went through almost fifty editions. The ridicule of which she speaks in Pen Tamar is perhaps exemplified by a remark made about her by the Earl of Minto, who said ‘She is, I believe, a blue-stocking, but what colour of that part of her dress is must be mere conjecture’. Through the novel, she seeks to address disrespectful attitudes such as this.

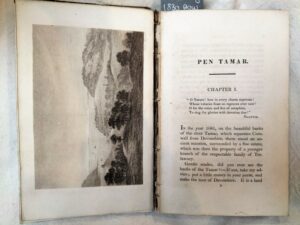

We are introduced to the character of Sir William Trelawney, the owner of a beautiful estate by the name of Pen Tamar, situated on the banks of the river Tamar. His home county of Devon is described as ‘flowing with milk and honey’, where ‘every charm of nature, every improvement of art, may be seen in perfection’.

In the opening chapter, Trelawney learns that a resident has been found for a small property on his estate. His initial pleasure at the news turns to distaste when he finds out that the occupier is ‘an old maid’, to which Trelawney remarks ‘O, plague take them all, for a set of malicious, spiteful, mischief-making devils’. He predicts that ‘here is an end of all the peace and quietness in the village. She will pry into every hold and corner of the parish, and make mischief every where’. The rest of the novel is then dedicated to explaining the roots of Trelawney’s prejudice, and mounting a defence against this negative generalisation.

We travel back to his youth, where we learn of his deep attachment to his childhood friend Matilda Heywood. His hopes of blissful matrimony are dashed when his spiteful maiden aunt bends the ear of his alcoholic father, who then forbids the union. Heartbroken, he embarks on a grand tour of Europe with his friend Mr Hamilton. During his absence, his aunt writes to him to tell him that Matilda and her father were both drowned while travelling to America, to escape the Civil War. Ever unsympathetic, his aunt expresses the hope ‘that you will now be disposed to make up for the past, and marry somebody proper’.

Utterly devastated, Trelawney throws himself into the conflict at home, distinguishing himself on the side of the King. He later marries, his understanding wife accepting ‘an union formed by friendship and esteem’ as he confesses to her that ‘he still loved Matilda Heywood’. It is at this point that the narrative turns its attention to Matilda’s version of events. Although shipwrecked, she was not in fact killed but was rescued from the sea by the eligible Comte de Clairville and his sister, who take her with them to Canada. She remains abroad for some time, anxiously waiting for news of Trelawney’s fate during the war. She learns both that he survived and that his father had passed away, clearing the route for their reunion. However, by the time she arrives in Devon, she finds that she is too late, and that Trelawney is already married.

A devout Christian, Matilda does nothing to threaten this marriage, but instead takes herself to Yorkshire, where she lives for many decades, remaining unmarried and dedicating herself to ‘only benevolent actions’. After the death of Trelawney’s wife, she travels back to Devon as an elderly woman and it is she who takes up residence in the cottage on the estate, much to Trelawney’s astonishment and delight, having believed her to have been dead for many years. Her virtue and respectability serve as a lesson to Trelawney, and to the reader, that an unmarried woman of sound Christian principles should not be exposed ‘to ridicule and contempt which they by no means deserve’.

The novel does not stand for modern feminism, and by no means argues for equality between the sexes. A comparison between the portrayal or Sir William and Matilda reveals several double standards: despite his persistent love for Matilda, William marries another, and no judgement is passed on this action. Matilda’s virtue, on the other hand, is demonstrated when she refuses the hand of the Comte de Clairville, telling him that ‘you deserve what I have not to give – a heart entirely your own!’ Upon their reunion after decades apart, Matilda’s regard for Trelawney is unchanged, and yet he is troubled by the ravages of time. ‘He had left Matilda Heywood lovely beyond description . . . he now saw a feeble and emaciated old woman’. In The feminist companion to literature in English, Blain, Clements, and Grundy argue that the novel ‘gives a mixed message: ostensibly defending both virtue and single women, it excuses the hero’s prejudice against old maids with one hateful example’.

Although written in 1801, Bowdler delayed the novel’s publication until after her death, suggesting some concern for the reception to its progressive message. Despite its problems, the book sincerely attempts to persuade the reader that an unmarried women should be judged by her own conduct, and not by unfair assumptions. It is clear that this is an important piece of writing within the context of its age, and worthy of a place within the history of feminist writing.

The Devon and Exeter Institution holds a first-edition of this novel, which is in need of restoration work. If you would like to help preserve this important book for future generations, please visit our ‘Rescue a book’ page to find out how to donate.