Take part in our Big Draw Event – Capturing Unusual Creatures

Beth Howell investigates curiosity in the animals and wildlife described and depicted in 19th century books of exploration in the collections of the Devon and Exeter Institution - what animal can you draw?

The 19th century saw a host of British and American explorers travelling to farther off regions than ever before. Usually, as Britain was constantly looking to expand its growing Empire these expeditions were carried out to take note of potential places for further settlement. Many of these accounts demonstrate an interest in cataloguing not only the topography of the visited region, but its animals and wildlife. As the Devon and Exeter Institution was itself created to enable learning and indulge curiosity during this time period, it is perhaps unsurprising that many such volumes appear amongst its collection.

One example is Captain James Mangles’ compilation of Papers and despatches relating to the Arctic searching expeditions of 1850-51-52, together with a few brief remarks as to the probable course pursued by Sir John Franklin. This collection includes the account of Dr Elisha Kane, an American explorer who went to the Arctic in the 1850s in search of Franklin, who had mysteriously disappeared in 1845 during his final trip to the Arctic. Though Kane was unsuccessful in finding the gentleman in question he delivered a series of lectures about his findings, including his observations on the auk- “about the size of our teal” and the brent goose- “wonderful.” He also says seals appeared in “extreme abundance,” whilst “the reindeer, the bear, and the fox, also abounded in great numbers.” Though in this case Kane was largely focused on the animal resources in order to consider the likelihood of Franklin’s survival, many individuals undertook similar counting exercises to assess a region’s potential for hunting and for food. How, the imperial mindset questioned, could a land be plumbed to further the industry and economy of Britain?

An individual with greater experience of the Arctic was Sir John Richardson, who travelled with Franklin on his journeys to the region in 1819-22, 1824-27, and spearheaded his own trip in search of Franklin in 1848-9. He is credited for making more extensive and accurate surveys of the Canadian Arctic Coast than any other explorer, but many of his writings display a particular interest in natural history. In his The Polar Regions printed in 1861, Richardson talks a great deal not only about the animals he currently sees – polar bears, reindeer, brent geese, lemmings – but also extensively discusses the remains of mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses. “From an early period of the Russian explorations of Siberia, the tusks of the fossil elephant or mammoth have been sought for on the shores of the Polar Sea as a valuable article of commerce,” Richardson writes. Not only, then, were living animals seen as food for future explorers, but the remains of those which had passed on could be used to sustain the expeditions financially-or otherwise. Grimly, Richardson admits: “at the mouth of the Lena, the entire carcass of a mammoth was discovered so fresh that the dogs ate the flesh for two summers.” Nonetheless, “The skeleton is preserved at St. Petersburgh, and specimens of the woolly hair, with which the skin was covered, exist in England.” Wonder was balanced with pragmatism; learning was balanced with living. In Richardson’s account, which does demonstrate a thriving interest in the zoological specimens around him as spectacles as well as food and fuel, this tension perhaps appears most profoundly.

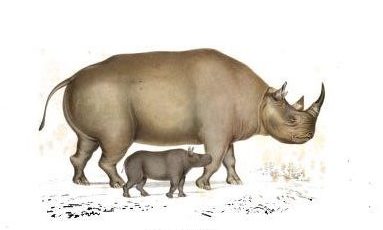

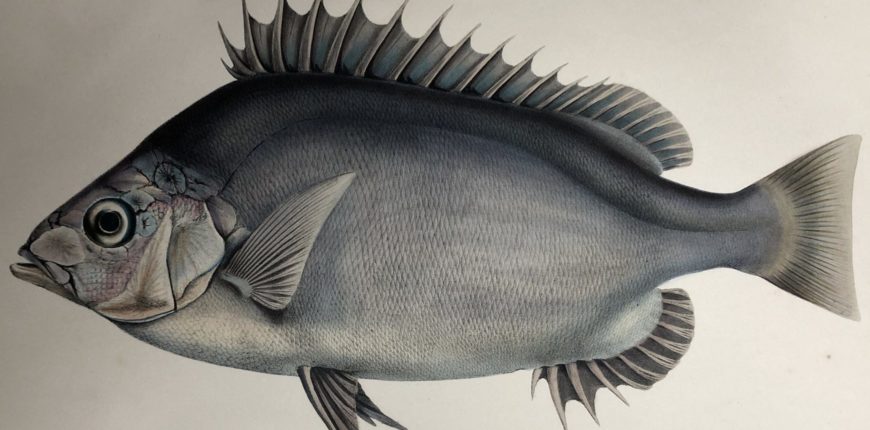

A writer who engaged with the visual spectacle of the unusual animals to an even larger extent, however, was Sir Andrew Smith. His explorations ventured into a very different part of the world: South Africa. His illustrated collection of the species he saw during his three-year expedition is truly a wonder to behold. Smith organised his descriptions into five volumes: Mammalia, Aves, Reptilia, Pisces, and Invertebratae, which were published with a series of coloured plates between the years 1838 and 1849. Smith had commissioned George Henry Ford, a young man from a settling family whom he met on his expedition, to provide the illustrations. Smith was confident of Ford’s gift for artistry, and declared “ a cursory survey of the plates will, I think, convince any one that they are the production of a master’s hand – a hand that depicts nature so closely as to render the representation nearly, if not equally, as valuable as the actual specimen.” When it came to portraying the animals he had seen for a wider audience, accuracy was clearly important to Smith. He described his observations as “an extensive and varied collection of objects of Natural History, many of which [are] new to science, and many others, though not new, comparatively little known,” and wrote personally to the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Glenelg, to help bring the volume to publication.

Nonetheless, there are amusing moments in Smith’s fastidious accounts. Of the Hippopotamus, Smith observed “Figure massive and very heavy, and the entire contour of the animal suggests to the observer the idea of a form intermediate between an overgrown pig and a high-fed bull, without horns and with cropped ears,” and “the legs are remarkably short, so that when the animal is standing, the most depending part of the belly almost touches the ground.” Of the rhinoceros bicornis, he noted its “clumsiness,” and the roughness of its skin “owing to its being intersected by a great number of wrinkles.”

No account of 19th century explorers and the animals they encountered could, however, really be considered complete without making mention of Charles Darwin. Darwin spent five years travelling the globe, though his theory of evolution is usually affiliated with his specific observations on the differences between finches on the Galapagos Islands, where he stayed for five weeks in the autumn of 1835. However, it seems his ideas really came to fruition after a conversation with the ornithologist and illustrator John Gould, back home in London. As an illustrator, Gould was more keenly aware of the differences the finches displayed, consolidating the ideas Darwin was already forming about species shifting and changing organically, rather than being placed as completed creations on the earth by God. If anything, these accounts tell us of the importance of close observation, and capturing how an animal looks and behaves as closely as possible in print or in paint, to preserve its likeness for a future audience.

If you would like to contribute to our “Big Draw Animals” event by adding your own animal drawing or painting, please do comment on our facebook page, twitter account, or email us.

Captain James Mangles’ Papers and despatches relating to the Arctic searching expeditions of 1850-51-52, together with a few brief remarks as to the probable course pursued by Sir John Franklin, Sir John Richardson’s The Polar Regions, Sir Andrew Smith’s Illustrations on the Zoology of South Africa, and a version of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species are all available to read freely on archive.org.

Beth Howell, Saturday Activities Co-ordinator