A British Science Week Special: Celebrating the Legacy of William Elford Leach

William Elford Leach (1791-1836) was a prominent zoologist, born in the height of the Age of Enlightenment in Plymouth, Devon. From a young age, he began to collect marine specimens along the Devon coast, and after embarking on a medical apprenticeship at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, and completing his M.D in Scotland, Leach turned to natural history in earnest. It was a career that would see him establish over three hundred genera, publish widely in the field of insect and Crustacea studies, but would also lead to losses, overwork, and early retirement.

In 1813, when the role was made vacant by George Shaw, William Elford Leach was made Assistant Librarian (a role later known as “Assistant Keeper”) of the British Museum’s natural history department, where he was responsible for the zoological collections. During his time in curatorial work, Leach established himself as a taxonomist of International renown. Inspired by the French texts he was reading late into the night, he made large reforms to the Linnean system of classification, particularly in conchology and entomology, in which he notably separated centipedes and millipedes into their own subphylum, Myriapoda. He soon became recognised as the leading expert on Crustacea, and he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1816, aged only 25. In terms of the naming his own “discoveries,” Leach tended to honour his friends and associates. Consequently, a total of nineteen species and one genus bear some derivation of “Cranch” after John Cranch, his friend and employee. Tragically, Cranch died during the ill-fated expedition of the HMS Congo in 1816, an endeavour which saw thirty-eight of the fifty-six crew members perish, most likely from yellow fever. After Cranch’s death, Leach systematically set about describing the specimens his friend had collected, a lengthy and difficult process which may well have contributed to his steady decline in the 1820s. Nine of the over 380 genera Leach established, in a latinised or anagrammatic form, also bear the name Caroline, though the identity of this woman and her relationship to Leach has never been discovered. The marine isopod crustacean Cirolana cranchi honours both these figures from Leach’s life. In late 1821, he suffered a nervous breakdown, and retired from the museum to convalesce in various locations around Europe.

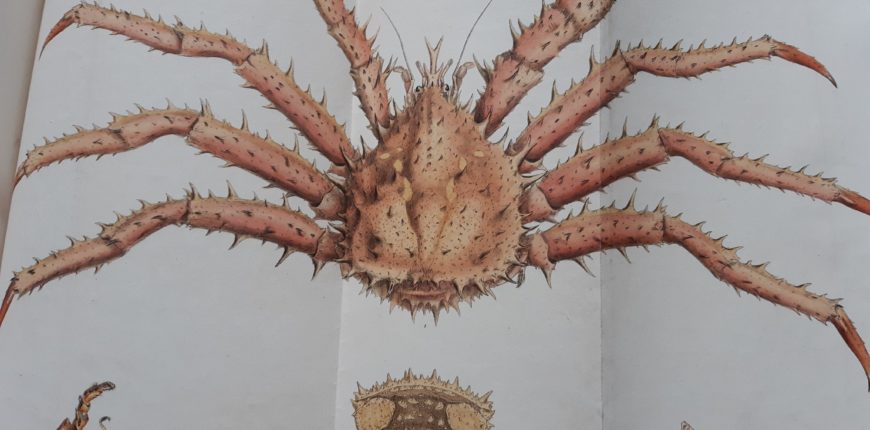

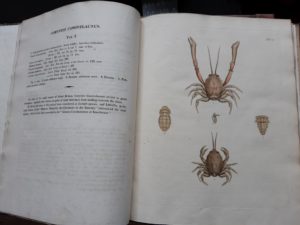

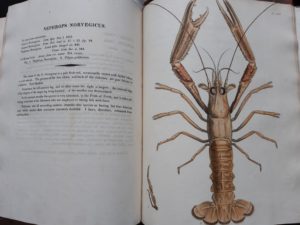

Leach’s written legacy is impressive. He authored several articles for the Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Edinburgh Encylopaedia on Crustacea, as well as publishing thirty-one papers in the Royal Society Catalogue and seven pieces for the Transactions of the Linnean Society, three of which were on insects, all within the space of a few years. Perhaps his most ambitious intention, however, was to create a multi-volume illustrated dictionary of British Crustacea. Malacostraca Podophthalma Britanniæ, or a Monograph on the British Crabs, Lobsters, Prawns, and other Crustacea with pedunculated eyes, was published between 1815 and 1817, with coloured plates by James Sowerby. The project would remain incomplete at the time of Leach’s sudden death, in August 1836, from Cholera. Nonetheless, an edition of the genus Cancer, with 54 illustrations, remains one of the treasures of the Institution. Whilst Leach is perhaps one of the lesser-known names in early science today, his commitment to zoology has been honoured in the species that bear his nomenclature, such as the blue-winged kookaburra, Dacelo leachii. His slightly eccentric, but charming naming system remains in many of the species we still recognise today.

In 1837, a year after his death, Dr Francis Boott, the secretary of the Linnean Society, declared: “Few men have ever devoted themselves to zoology with greater zeal than Dr Leach.”

Photographs from William Elford Leach, Malacostraca podophthalmata Britanniae ; or, Descriptions of such British species of the Linnean genus Cancer as have their eyes elevated on footstalks / Illustrated with figures of all the species, by James Sowerby (Lambeth, England : James Sowerby, 1815).