An Invitation to Create #8 – Victorian fern lettering

Victorian Fern Lettering

Did you know that for many Victorians, ferns were a prized possession? You may not notice it at first glance, but many Victorian texts, fabrics, bookplates, print borders, tins and pins are adorned with ornamental versions of these leafy plants. This fondness for ferns was a trend that even extended into the early 20th century- the next time you have a custard cream, you might want to take a look at the design on the biscuit!

This nineteenth-century fever for ferns also found its way into the Illustrated London News, a Victorian periodical that sought to document contemporary events in a very visual format. In the header of many of the volumes which are held here in the DEI’s collections, the words “London” and “News” are adorned with intricate leaves, a hallmark of the newspaper’s innovative strides into illustration and printmaking. However, the ILN’s issue dated July 1, 1871, is particularly concerned with this leafy connection. In a carefully-rendered full-page illustration created by the talented Helen Allingham (a watercolour artist and illustrator who would later also provide the illustrations for Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd, 1874) a party of respectably dressed Victorians are depicted “Gathering Ferns,” intently searching among the foliage for the rarest specimens.

The fern trend was certainly of its time, but it also had a distinctly Devonian root. It was Charles Kingsley, the Devon-based author of The Water Babies, who coined the term “Pteridomania” (meaning “Fern Madness”), in 1855. Kingsley would, of course, have benefitted from the knowledge of his sister Charlotte Chanter, who wrote Ferny Combes : a ramble after ferns in the glens and valley of Devonshire, in 1857. This charming little volume encourages us to walk with Chanter in her native Devon, and communicates in the most expressive terms the joy of hunting for these leafy specimens:

“To tell the exact spots where each plant grows would be depriving you of one of the greatest pleasures and interests of the pursuit, namely discovery for yourself. If you take a tour through Devonshire, and use your eyes as you travel, you will hardly fail to find most of the ferns I shall describe to you; but it is no exercise of observation to walk straight to a given point, pluck a leaf, and walk back again; no, a fern collector, if he really wish to make discoveries, must be ever on the alert, ever watching; even on a wall you have passed a hundred times without observing anything curious, the hundred and first time you may find a treasure you did not think was within fifty miles of you.”

The idea of these fronds and ferns being as precious as “treasures” may seem alien to us now, but at the time the fern family was sincerely experiencing a Renaissance- newly elevated from a position which had once perceived them as being akin to the commonest weeds. This turnaround was of course in part of a condition of the new greenhouse mentality- innovations in prefabricated sheets of glass allowed for large-scale structures in which plants from far-off climes could live and breathe safely within the British climate for the first time. In their own homes, the Victorians also created living terrariums, or “Wardian cases” for their more domestic plants.

Ferns found their way into the homes of scientists and the hearts of amateur collectors alike. Charlotte Brontë was one such fern enthusiast. She kept her own “fern-book,” a volume of pressed and preserved ferns, during her honeymoon in Ireland in 1854, and indeed it seems fitting that she also ended her most famous novel, Jane Eyre (1847), with an image of her protagonists reconciling at “Ferndean” Manor. Jane is referred to as a “fairy” by Mr Rochester throughout the novel, and it is unsurprising that this place forms the final point of rest, a fairy, dream-like dwelling drawing on the traditional idea of ferns as leaves from a supernatural realm.

The delicate intricacy, but also the hardy integrity of ferns made them suitable subjects for pressing and preserving, and also meant that they were particularly suitable for printing. The fern could be pressed to form the print of its own representation. Ferns therefore strode the line between fragile fairy forms, and leaves that suited the pages of new industrial print. It is this connection between print and ferns that inspires our make today.

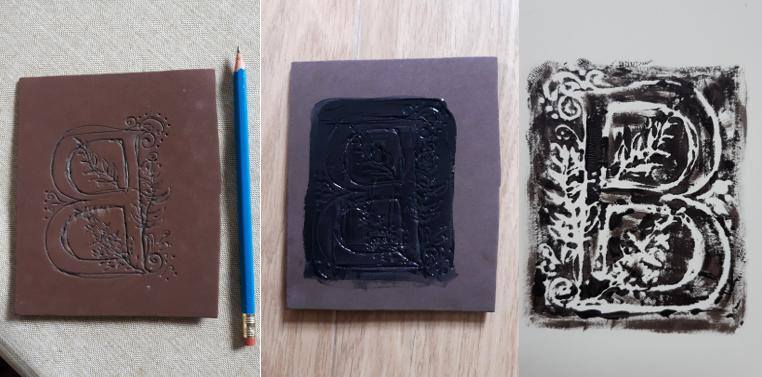

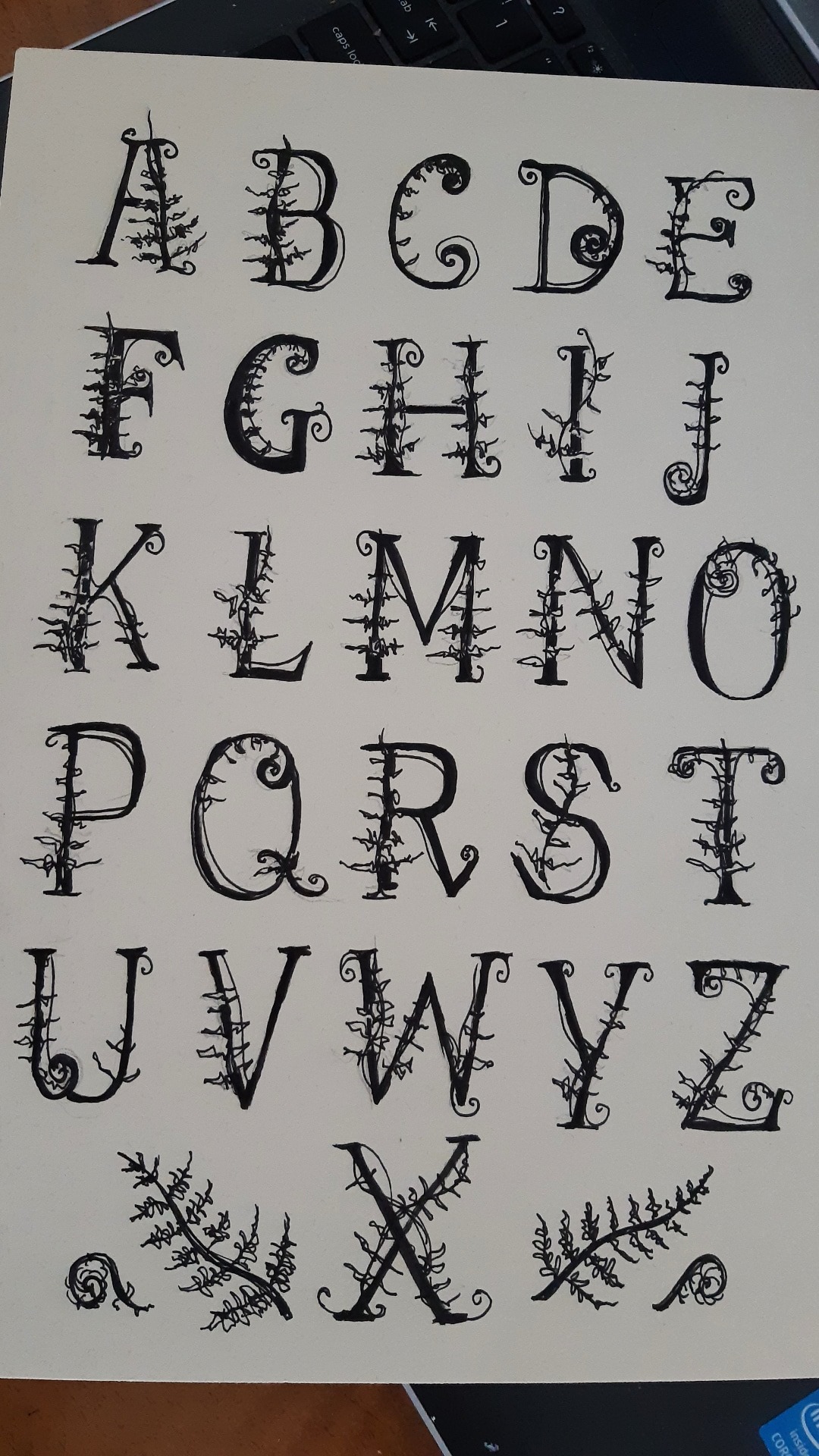

Taking a piece of foam (you may also use the bottom of a styrofoam or polystyrene takeaway tray), take a sharp pencil and lightly draw the design for a letter (make sure to draw it backwards!). Include fern leaves and fronds as decorations, drawing inspiration, if you wish, from the letter sheet attached below. Once you have drawn out your letter, press into it further with your pencil. Once this step is complete, cover your design with black paint. Then, turn the design over onto a piece of card. Press, and then reveal.

These letters can be used as stamps for your initials. What stories will you tell, and then sign, with your fern-inspired print blocks?